In this fifth of a six-part series, Ellen Besen looks at Oscar-nominees Finding Nemo and The Triplets of Belleville and compares and contrasts their core analogies.

Animation Wars: CG giant Finding Nemo battles 2D feisty indie The Triplets of Bellville for the Oscar. All Finding Nemo images © Disney Enterprises Inc./Pixar Animation Studios. All rights reserved. All The Triplets of Belleville images © 2003 Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc.

Welcome to Oscar 2004! Last year there really was no contest, Spirited Away was so far ahead of the pack. But this years competition has caught my attention, with two of the three nominees worth considering. So in this corner, we have the popular CG giant, Finding Nemo. And in this corner, the feisty, independent 2D The Triplets of Belleville. With Disney declaring that drawn animation has had its day, this is a perfectly timed Battle of the Techniques.

First, a little note to the folks who felt I was picking on Pixar in the last article, because yes, I do offer more criticism as well as some praise for Nemo here. As a fan of Pixar, I am taking the stance of loyal opposition. So I am not picking on them, I am challenging them. With that said, lets take a look at the films.

As I discussed in some detail last time, Nemo is not a perfect film. And neither is Triplets. But both are interesting, each in its own way. And surprisingly, like you and that kid you loathed in kindergarten who later became your best friend, while these films are strikingly different from each other in most ways, underneath they actually have something in common: their core themes are almost identical.

This gives us the relatively rare opportunity to compare how two current, high profile animated features handle the same subject matter. There are some interesting things to be learned when the starting place is similar but the resulting films are so different.

So what exactly do they share? At first glance, you think, what is she talking about? Nemo is all oceans, reefs, fish tanks, dentists offices, sharks in denial, spoiled children, sewer systems, pelicans, clown fish. And Triplets is bikes, races, old dogs, trains, mobsters, aging singers, big cities, hot jazz. Other than that voyage across the ocean, where is the common ground?

replace_caption_besen05_findingNemo-gill&ne.jpg

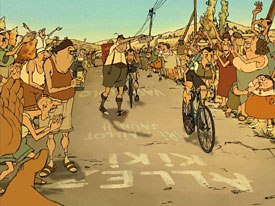

Well, if you think about it, you realize that both films are about parenthood gone wrong. Marlin loses Nemo by trying too hard to hold him back and Madame Souza loses her grandson, Champion, by pushing him too hard in the wrong direction. In both films, the adults must recognize their mistakes and change direction in order to get their children back. But from here, the films diverge.

With its underwater setting, Nemo discovers a hidden world. How fish go to school, the ride on the ocean current and the intricate workings of fish tank society are all whimsical and thoroughly delightful. The film also has two great villainous characters in Bruce the shark and the nasty niece. I would love to have seen more of both of them.

And Nemo introduces lots of potentially rewarding ideas: anxiety, forgetfulness, the difficulty of undoing ones essential nature, the danger of both open and closed spaces. But instead of building on them -- letting them add up to something more the film plays them for the immediate laugh or thrill, or simply uses them as plot devices.

Story wise, Triplets is more than the sum of its many parts.

Triplets, for its part, sorely lacks a strong villain one who is worthy of the scope of the films themes. There may have been potential in the sodden mafia chief but it stayed thoroughly under wraps.

And the film is weak in terms of situation: too much of the story feels nailed down, stuck within the boundaries of a live-action world of gangsters and car chases. These sections are slow, dull and predictable. This is all the more frustrating when compared with the parts of the film that lift off into a realm of dreamy surrealism.

What about its strengths? One is that it ties the basic story of a grandmother who wants her grandson to succeed to a central analogy: a race. From the race comes the idea of championship and this is where Triplets begins to have fun with themes. Here is a film that does add things up.

By making the story more specific (Grandmother doesnt just want her grandson to succeed, she wants him to become a sports champion) and setting up some key contrasts, this now becomes a story about the nature of championship itself.

It always fascinates me to realize how effectively we can communicate in animation by contrasts: cat and mouse mortal enemies, short and tall best friends, the whole wonderful opening sequence of 101 Dalmatians where we discover the perfect love match for Pongo and Roger by first seeing a series of mismatches.

In Triplets, we see the glamour of winning the race contrasted against the drudgery of bringing up the rear. We also see that Grandmothers dream of Champion winning only sets him up for a life of racing literally to nowhere. Most importantly, we see Grandmothers devotion. Throughout the film she is the unsung hero.

And now we know why the story revolves around a bike race. This provides the contrast, the model for the official, quite meaningless idea of a champion versus the true champion who, motivated by love, performs miracles without expectation of medals, ceremony or publicity.

And what miracles they are: the winner of the Tour may cycle up a mountain but Grandmother crosses the stormy Atlantic in a peddle boat, hot on the heels of a steamship. This surreal sequence makes great use of animations license for exaggeration, pitting the giant ship against the tiny pedalo. It takes the idea of the impossible task to new heights and manages to extract humor, pathos and drama from the situation simultaneously.

This leads finally to a questioning of what in life has real value. And now, the whole film comes into focus: there is a constant comparison of values, media spun glamour versus simpler pleasures, going on throughout the film.

On the one hand, Fred Astaire is revealed as a fraud, the prosperous citizens of Belleville are fat and glum. And the workers, the mouseman and ultra obsequious maitre d, only demonstrate how regular folks have to limit and distort themselves in their strivings to survive in this crazy system.

On the other hand are three points of comparison: Bruno, the underdog, who embodies all the fears and obsessions with past wrongs (he never does get over having his tail run over by that toy train) that everyone else suppresses in their grim run at worldly success; the triplets, conscience of the world and happier than anyone in their nasty tenement apartment, not to mention their all-frog diet; and, finally, that last image of our heroes sailing across the bridge, their platform like a schooner with a film screen for a sail, into the future and a projected virtual reality.

The magical quality of this last image is Triplets at its very best. I just wish Chomet had pulled out all the stops and taken more of the film to this level (though maybe thats a scary thought the released energy might just blow out the projector oh what the hell, bring it on).

Parenting is the one theme both Finding Nemo and The Triplets of Belleville share.

Interestingly, the film also works well in the quiet character moments, particularly at the beginning of the story.

Here the contrast with Nemo is striking. Lacking a central analogy as a guide for developing performance, Nemo falls back on melodrama. Much of the emotion is invoked by oversized events that function like tabloid headlines: Fish Family Wiped Out! Fathers Only Child Abducted! Shark Attack! Jellyfish Attack! Young Fish Trapped in Tank Filtration System! etc., etc.

This approach has its place in fiction but the audiences engagement with it is a reflex rather than true emotion. Any kid who gets trapped in a well is going to get an outpouring of sympathy, even from total strangers. But such sympathy lacks roots and in time the strangers will be distracted, even if the kid is still trapped, unless his situation continues to escalate. We see this phenomenon play out in the media all the time.

Triplets asks its viewers to question what in life has real value.

So as an exclusive fictional device, this approach traps the filmmakers into striving for ever more adrenaline producing events, regardless of whether they make sense in the story or not, just to hold to the audience. Nemo has 18, count em 18! crises including not one but three uses of that moldy Disney device, where we think the hero is dead but he isnt

On the plus side, this can produce a wildly exciting ride. Nemo provides this at a level which Triplets cant begin to match. The risk they run, though, is audience fatigue and the Barney effect, in which six-year-old kids, former Barney the dinosaur addicts, develop a special kind of hatred for their former idol born from a recognition that theyve been emotionally duped.

By contrast, Triplets underplays. For example, we never find out why Madame Souza is left with the care of her grandson, we only know she is distraught because she doesnt know how to make him happy. This plays out beautifully by keeping things firmly within her POV. The audience has no more clue than she does about what he wants. We dont even have words to go on which nicely exaggerates the reality of how difficult it can be to break through to a troubled child.

This puts the audience in the role of detective, scanning the screen for signs about what will solve the problem: a very satisfactory approach to audience engagement, indeed.

And this brings us to our final point in 2004, can 2D drawn animation still engage an audience, particularly an American one or are we inevitably moving into an all 3D world?

Films such as Spirited Away and Triplets would tell us nothing is inevitable. It depends much more on what we choose to do. Certainly, though its story is somewhat wonky, Triplets uses some sophisticated storytelling techniques as noted above, and even makes a nice, if not truly integral use of its technique. In particular, it finds an interesting use of dimension as a way to distinguish between realities.

Triplets underplays its drama, forcing the viewer to become a story detective.

There are, in fact, three realities in this film: the old days (flat, rubber-hose inspired animation and design), the present (a more refined, angular style with what appear to be some modified flattened that is 3D elements) and surreal live action which in this opposite world plays the role that animation plays in ours. So this is a 3D world after all just not the typical one.

The negative assumption about 2D is based on the dismal track record of recent Hollywood attempts. This reminds me of the belief that held sway for many years before 1990, that American audiences wouldnt watch a primetime animated TV series. For that matter, pre-1936, there was a firmly held belief that American audiences would never sit through an animated feature, regardless of technique. Given that it was Walt himself who proved this wrong with Snow White, it is quite telling to listen to Michael Eisner declare that 2D is dead.

This kind of thinking comes from a failure of vision: one that is too shortsighted to see recent successes that undermine the belief or to perceive self created roadblocks or to make the leap to something that hasnt been done yet. Back in the 1930s, the argument against animated features was based on the assumption that animated characters could not be made emotionally engaging enough for audiences to identify with them.

It took vision to say that because it hadnt yet been, didnt mean it couldnt be done. And with that in mind, Disney set up a plan to create animation that could do precisely that. Of course, there is a whole debate about whether he did the medium a favor by taking it down this path in fact the history of animation since his decision could be said to be precisely that debate. But one way or the other, he still deserves the credit for having both the vision and the will to make it real.

Before The Simpsons, TV producers didnt believe that adults would watch primetime animation. © 2003 FOX.

The debate about primetime TV was a case of producers not being able to perceive a rather obvious case of cause and effect. Because they believed adults wouldnt watch animation, they only made programs for children, and because the animated programs were only for children, adults didnt watch them a lovely case of self-fulfilling prophecy. Of course, the real problem wasnt technique; it was content as The Simpsons and then many other shows subsequently proved.

Objectively, then, the case is simple. When it comes to audience response, there are two key points: compelling theme material and technique that serves it well. Make a good 2D film, such as Triplets and of course, give it some publicity and audiences will come. Or at least, there is a reasonable chance that they will.

But producers will be producers and they arent necessarily known for their objectivity. In fact, there is denial factor here that hasnt really been touched on, one that goes beyond tech debates and producers and moves to the wider, whither animation? (oh, I just really wanted to think of all of you saying whither to yourselves...).

But seriously, we have to do a little therapy next time as well as talk about one of the toughest of writing problems how to end a film. How appropriate for a last article, dont you agree?

So is it over, do you think? Yes, it is over

Ellen Besen studied animation at Sheridan in the early 1970s. Since then she has directed award-winning films both independently and for the NFB, worked as a film programmer and journalist, taught storytelling and animation filmmaking at Sheridan and given story workshops at many institutions and festivals, including the Ottawa International Animation Festival. She is the director of The Zachary Schwartz Institute for Animation Filmmaking, an online school that specializes in storytelling and writing for animation.