Animating under the camera with sand or paint on glass is a tricky feat. Here a host of experts offer their tried and true methods.

We asked leading artists who work with two of the most popular and striking under the camera animating techniques, sand, and other loose materials, and paint on glass, to reveal different tips and tricks that they have learned through trial and error. We hope that they will encourage you to experiment in these areas as well as other under the camera animation techniques. All of these artists attest that what makes these techniques so difficult is what makes them so appealing -- that fleeting sense of spontaneity of creating an image, only to replace it with the next, destroying while creating.

On the subject of sand, we hear from Caroline Leaf, Maria Procházková, Eli Noyes and Gerald Conn, and for paint on glass, we hear from Alexander Petrov, Wendy Tilby, Eleanor "Ellen" Ramos and Lyudmila Koshkina.

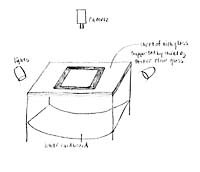

This sketch by Caroline Leaf illustrates her recommended set-up for sand animation. © Caroline Leaf.

Sand

Caroline Leaf

I worked with white beach sand poured out onto an underlit piece of glass in a darkened room. The only light in the room came from the lights under the sand animation, letting the sand become a black silhouette against a white ground. Even though it was very fine sand, I needed a large field size to make detailed sand images. The field was approximately 24 x 18 inches. The best way to light such a large surface evenly turned out to be with a light on either side of the table pointing down to the floor and bouncing back up to the underside of my working surface from a large curved piece of white cardboard lying directly below on the floor. An important side benefit of this indirect lighting is that you are not looking directly into a light bulb while you work. This can strain your eyes, not only because of the brightness, but because the eye struggles to accommodate the big contrast between light and dark. Go for the weakest light possible behind your artwork whenever working with underlit images.

Caroline Leaf, often referred to as a pioneer of sand animation, is shown here working on her first sand film, The Owl Who Married a Goose. Photos courtesy of Caroline Leaf.

When I am setting up for sand animation, I always look for glass, not plexiglass, on which to work. With friction and rubbing, plexiglass builds up static electricity, which makes the grains of sand jump around in a frustratingly independent way, particularly in dry climates like Montreal in the winter. The best glass I have found, though rare and expensive, is called flashed opal or milk glass. It is window thickness clear glass with one side of very thin white glass. It is often sold by large glass manufacturers supplying photography stores. Choose a piece of glass without bubbles in the white flashing and have the white side up when you work to avoid problems with reflections within the glass.

Maria Procházková - Stopáé/Footprints

When I decided to realize an animated film on such a simple, matter-of-fact subject as traces, footprints, human touches and their passing character, I became perfectly aware of the fact that this film could not be a drawn one, and that the chosen animation technique should express the basic idea that I was trying to share a passing, transitory feeling, the feeling of the impossibility to preserve something. Within the small scale of this film, I hesitated between sugar and flour, but finally opted for sand, due to its beautiful color. Also, it does not imitate soil. On the contrary, it may be fixed for some period of time with water. For me, the sand was a very good material with which to work. I used a layer of about six centimeters thick in which I imprinted with small molds (printers). I sprayed the sand in short intervals with water so that its quality of looseness did not change, and simultaneously, in order to prevent the sand from turning more pale. I was careful not to get it darker due to excessive watering. The sand turned dry very quickly under the powerful film lights. I sometimes had to pour in water even during the individual shots, which constituted a big risk of moving the footprints already marked. I used a dense sieve for the sand used in close-ups so that this sand did not seem courser than the sand in the whole-shots. The aspect that I enjoyed most in this project was that everything was appearing directly under the camera and in the same way, was disappearing in subsequent shots, in order to give way to the creation of something new.

Sandman. © Eli Noyes.

Eli Noyes

The sand animation I did was back in the mid `70's when I made a short film from experiments I did under the animation stand I kept in my loft in New York. The experiments turned into a short film called Sandman. Then I convinced the Children's Television Workshop to let me make the entire alphabet, upper case turning into lower case letters, using sand animation and the little characters I invented when I did Sandman.

Tricks and tips? First I got my sand from an aquarium supply store. It came only in white so I sprayed it black so it would show up. Then I made a little sandbox out of strips of wood on a big piece of glass underlit with a light box. I experimented with all kinds of brushes, little squeegees, tools to manipulate clay with, etc. I found a medium stiff paintbrush the best tool for pushing the sand around to make my characters. The most useful tool was a simple invention made from a mayonnaise jar and some tubing from the fish store. One tube pierced the cover of the mayonnaise jar and went to the bottom of the jar. The other only went in an inch or so and had a sort of filter taped over it made from lens tissue. Sucking on the short one would allow me to use the longer one as a vacuum cleaner to pick up pieces of sand that couldn't be brushed away. That helped a lot when I wanted to make clean lines, or put white holes in dark shapes.

The most important thing for me was and still is to let the material I am working in speak to me and help me derive an aesthetic particular to it. The sand naturally makes certain shapes when you push it around. It tends to leave trails which can be of use if you don't try to fight them. I would say that a big dose of this philosophy would be a very useful cheat and tip for anyone wanting to work in sand. Experiment, and experiment to find your design.

Gerald Conn at work in his studio. Courtesy of and © Gerald Conn.

Gerald Conn

I have been using sand in my animated films for about ten years. I prefer manipulating materials directly underneath the camera as I find this working method leaves room for greater spontaneity. To me the process seems similar to modeling forms in clay, where you are constantly adjusting and thereby improving on the image as you go along. I storyboard my films quite carefully and usually bar-chart the animation to music as this gives me a structure with which to work.

For me sand animation seems particularly suited to certain subject matter. I don't use many figures in my films but I like dealing with topics that involve animals and natural phenomena. I also like to include tracking and zooming shots in my films for dramatic effect. These shots have a particular quality in this technique because you are creating the imagery as you animate rather than it being a purely mechanical camera-move. I often use inks on a second layer of glass in order to combine color with the sand animation. It's difficult to do anything detailed in this way but I find that it gives the animation an extra dimension.

I would say the most important tip when working with sand is to use a thin layer of the material on the glass. This enables you to control the tonal quality of the image, which in turn will give the animation a greater sense of form. I personally prefer to work with a fairly course grade of beach sand. This gives the animation a grainy look that I like.

Paint On Glass

The Mermaid. © Alexander Petrov.

Alexander Petrov

In animation film, painting on glass is like painting on a canvas. My work deals with subjects like portraits, landscapes, and historical events in a realistic style. Painting on canvas is creating an idea with one subject. Animated films allow the possibility of finding multiple ideas; therefore, the themes grow larger, more detailed, and are more dynamic than paintings on canvas. This animation technique gives me wonderful opportunities for variations on a subject. I prefer working with living ideas, changing the details of the subject, and making transformations during the filming process.

I stick to a very strict art direction, and with my storyboard, I know where I need to arrive, but how can I get there? What will be the next scene? Every time, it's a surprise, good or bad. For example, in the film, Dream of a Ridiculous Man, there is, at the end of the film, this episode with the hero observing Hell. He looks down and sees a little man in his hands. When I was filming this scene, I didn't like the final, and the skin color of the little man bothered me. So, I decided to change the color of the skin for a white sculpture skin. With this changing, the little man, made of sand, could kill himself. The clay was falling through the hands of the hero, and leaving a sense of destruction. I found this symbol at the end of the film! That's what I like with this technique of painting on glass -- I can improvise with the subject.

I also prefer working with real people. In the film The Cow, I chose my son Dimitri for the role of the child. For Dream of a Ridiculous Man, the hero was my camera man Sergei Rechetnikov and in The Mermaid, I used some people from my neighborhood and again, my son Dimitri. It's essential to work with references because my work is realistic and I try to keep the real personalities in my characters. It is wonderful to paint people that I love.

When I'm doing an animation film, just like painting a picture, I let out my energy and my feelings in the colors. With the animation, I'm searching to express ideas, but I also try to find the harmony of life. This harmony I can find during the filming process with mistakes and successes. Step by step, I try to project the beauty, the force and emotions within the animated image.

Wendy Tilby used paint on glass for this Acme Filmworks commercial.

Wendy Tilby