Oscar®-winning director Gene Deitch has much to say about Motion, Music and Magic in his updated essay on the director's role in an animated project.

Editor’s Note: The following is an updated essay by Oscar®-winning animation director Gene Deitch, originally written as a keynote address for the Da Vinci Days art, science and technology festival in Oregon.

I was amazed that I was invited as keynote speaker at an event with such a lofty title as “da Vinci Days.” I suspect it’s because they found out that I’m left-handed. Otherwise, they didn’t give me enough time to grow a long gray beard, and I’m sure I could do that.

However, I have invented stuff. My most famous invention is the hollow chopstick – the first basic improvement in chopstick design in 3,000 years, allowing one to slurp up wonton soup with the same implements that grasp chicken Kung Pao. OK, so you’ve never heard of this astounding invention, but hey, Leonardo’s helicopter never got off the ground either.

My keynote theme, “Motion, Music, Magic,” is something I do have some opinions about.

Motion, first of all: I am someone who never sits still. I drove my mother crazy, because I could never sit quietly. I had to constantly fidget and move. To this day, I always have to be doing something, going somewhere. Motion is what I am constantly in.

Secondly, there is Music. I know all about music. I cannot sing in tune. I cannot play any musical instrument. I cannot read musical notation. I cannot dance. But “I got rhythm.” I am an annoyingly constant hand drummer…even if I have no drum handy. In spite of these obvious bedevilments, my whole life has been bound up in music. In my film work, I’ve had a hand in the creation of hundreds of musical scores. I constantly have music and melodies in my head. But when I try to sing them to my film composers, they tell me, “Gene, there are no such notes!” But musicians to me are magicians. They magically seem to get the idea, or stubbornly come up with a better one. And that brings me to Thirdly:

Thirdly, I have always been fascinated with Magic, and from a very early age I seemed to grasp what magic really is. My close friend and colleague, actor Allen Swift, is also a magician, and he put the principle into simple language: “In magic,” he informed me,” the moment of Action, and the moment of Effect are always different.” Magic is an entertainment based on deception.

I suppose it were my inclinations in motion, music and magic that led me to be a film animator, and, I suppose, what led me to da Vinci Days.

Motion, Music, and Magic are three pillars of show business, (following closely in importance just behind Money, Maliciousness, and Madness.) These same elements operate even in the once obscure corner of show business that we occupy: movie cartoons.

Movie cartoons are now big business – very big business. That aspect of it however, I have managed to avoid. I’ve had some flings at it, but what I’ve been mainly doing is still relatively obscure Little Business. After dabbling at the Big Time, luck and fate guided me into a different direction. I’ve spent the largest part of my career adapting children’s picture books as short animated films. My main fans are underpaid grade school teachers and librarians.

It happens that my line of work, making animated films, is all about motion. After all, it is part of an art & craft formally known as Motion Pictures, “Movies.” If you press the Pause button while viewing a movie, it is no longer a movie. A movie must be in motion or it’s just a still image.

Ordinary objects have three dimensions: length, width and height. But movies - and music - exist in a fourth dimension, the dimension of Time. If a musical instrument, an orchestra, an audio recording, an iPod, or whatever may be producing music – suddenly stops – the music vanishes! One might even extend this thought to a book. A book is just a wad of paper sitting on a shelf, until the actual time it is being read. While a book is being read, the pages turned, it too can be said to be in motion. When you stop reading it, it reverts to just being a dead wad of paper. If our hearts stop, or we cease to breathe, we are dead. Life is Motion, and a good motion picture comes the closest of any art to the representation of life in motion.

So when I am thinking about a movie as I am making it, I am thinking about motion. I’m not just thinking about a series of still images. I must think about how individual scenes flow together; one scene picking up the baton from a previous scene, and passing it on to the next, and always thinking about the final scene. In continuous motion, I’m heading for the final scene.

Thinking about the dimension of time requires a special mental adjustment. A popular phrase we often hear these days is about this or that “point in time.” The fact is, there is no such thing as a “point in time.” No matter what we are doing or not doing, time is always in motion. The only physical thing I can think of, as an analogy of time, is a river or brook.

If we stand on a bridge and look down at a river, it flows past us. If we come back the next day, or even a few moments later, that river may still have the same name, but it is in fact an entirely different river – all new water! If we jump into the river, we may flow with it, but in the case of time, it is always flowing past us. So there is no such thing as “now.” We cannot grasp at “now.” “Now” is constantly becoming “Then.”

So “time” as we know it is an inexorable, constant flow. But there is an internal component of time: Rhythm. There are broad rhythms that we know as geological cycles. The Ice Age came and went, and may come again. There is the regular rhythm of the seasons, the rhythm of the moon as it waxes and wanes, never pausing in its beat – the rhythm of the days, the sun marking day and night, day and night, day and night…. And there are our personal rhythms – the beating of our hearts, our breathing, the regular pace of walking. Is there any doubt about why we humans created music?

There is rhythm and counter rhythm all around us. In Bali and Java, they have a belief that music is going on constantly, and that musicians simply join in on the beat from time to time, and when the musicians stop playing the beat and flow of the music continues unheard until they again join in and give it voice. Each culture has its own patterns of rhythm. I think I know why our American musical culture has over-ridden everyone else’s. When I first came to Czechoslovakia in 1959, I became conscious of that. I had long been a jazz fan, so I was taken to a Dixieland jazz concert in Prague. I noticed that when the audience became excited by the band, they would clap on the main beat: “Clap-clap-clap-clap-clap.” That kind of clapping is inherent in the Czech national folk music, but it effectively deadens jazz music. American audiences learned to clap on the after-beat, “boom-CLAP, boom-CLAP, boom-CLAP, boom-CLAP.” It’s the lift of the after beat that we learned from the African slaves that became the core of jazz and syncopated music, all the way down to today’s Rock– the infectious beat that conquered the world! The way the Czech people clapped to jazz music bothered me, but I’m happy now that they’ve learned mainly to clap on the after-beat.

That after-beat actually represents contrast. Contrast is the essence of all art, musical and graphical: loud-against-soft, slow-against-fast, large-against-small, dark-against-light, straight-against-curved, near against far. In film work, that rhythmic contrast is called “timing.” Timing is something I try hard to work with. Timing is the element of animation that creates the effect of life.

So that’s it. Motion/Timing is what we live in, and Movies and Music exist in motion – and motion and timing are the basic cinematic tools that create the magic, our kind of magic trick. All magicians’ effects require that the Moment of Action and the Moment of Effect must always be different. When a magician says “Abracadabra, POOF!” there may be a puff of smoke, or a pistol shot, a flash of light, or other distraction, but the actual trick has already taken place. The magician - if he is clever – diverts our attention from the actual place and moment where the trick has happened. There were two different events involved, but we saw only one of them, the effect, not the actual action.

In movie work, we use exactly the same principle. We only let you see the effect. We don’t let you see what we’re actually doing. What we are doing of course is making the film at a much earlier time than you are seeing it. That’s obvious. But what may not be obvious to you is the truth about Special Effects. Special Effects are on a roll these days. Nearly every movie we see is loaded with special effects that constantly up the ante, gasp-wise. What you may not realize is that every single ordinary shot in every movie is some sort of special effect. Consider the old cliché, “The Camera Never Lies.” The truth is that the camera always lies! The cameraman frames each shot so as to let you see only what he wants you to see.

On the screen you may see two passionate lovers, apparently naked, engaged is what seems to be sexual intercourse. What you don’t see are maybe 50 film crewmembers engaged in their various tasks, just outside of the camera frame. What you don’t notice is that the scene is likely broken up into numerous shots from different angles. Each one of those shots requires special lighting adjustments and camera positioning. They may have been shot hours or even days apart, and not necessarily in the order that you see them… thanks to another magician called the Film Editor.

Imagine this simple screen action: An actor opens the door of a room, and is quickly seen coming through the door into the next room. For scheduling and set construction reasons, the shot of him or her coming into the second room might have been shot earlier than the shot of his exiting the first room. The shots were then spliced together in an order to achieve the wanted continuity. The first shot seen – may have actually been shot later, and may not be the adjoining room it is supposed to be, but maybe even be in another country! If it’s deftly done, the viewers accept the two rooms as being adjacent.

So what are you seeing? You’re seeing exactly what the director wants you to see, and in the order he wants you to see it. The camera is technically lying. Whatever truth there may be in a movie goes beyond the individual camera shots, to the sequence of shots that convey the story. If there is truth in a movie, it is how the director manipulates the technical elements of filmmaking to tell an acceptable story. So the magic of movies is just as much in the ordinary shots as it is in the spectacular digital effects we see so many of these days.

Those “The Making Of…” snippets on DVDs are carefully designed to make you appreciate some of the magic of filmmaking. The fragmentary tidbits are mainly designed to lock us in as rabid ticket buyers. But they do provide inspiring glimpses. If you’re perceptive, and you have the lust to be a filmmaker, all the tools you need are now available, even to people of modest means. And with YouTube, you have a chance to display your talent or lack of it. “Everyone can be a filmmaker!” I suppose that some will. If you are a potential da Vinci, and you want to be an artist, then here is the art form of our times!

Cinema has every element to make it the greatest art form of all time, and it was basically developed during just the last century. Whether on film, projected onto a movie screen, or digitally imaged onto a TV or a smart-phone, cinema combines nearly all known previous art forms into one: Story-telling, documentary journalism, drama, acting, mime, comedy, fantasy, painting, sculpture, music, song, dance, graphic arts, design, fashion, sculpture, architecture - art of every kind and description, can be combined into this one medium!

Did I say “the last century?” What if I told you that what we are doing had its clear roots over 35,000 years ago?

Whether we call it film, movies, cinema, video, or whatever, it is my feeling that the root idea for a dramatic sound and light presentation in a darkened room goes all the way back to our human beginnings; that it actually fulfills humankind's earliest artistic and storytelling cravings.

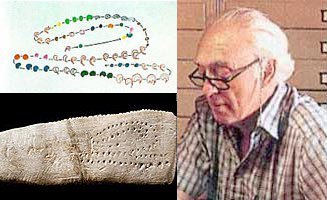

My late friend Alexander Marshack, who once was a photographer for the old picture magazine, LIFE, and also an early TV director, later became a foremost expert on the beginnings of human notation, writing, that is... He traced notation back at least 35,000 years. His story was told in National Geographic magazine, how early humans carved graphic notations on bones, showing where water was, and charting the seasons.

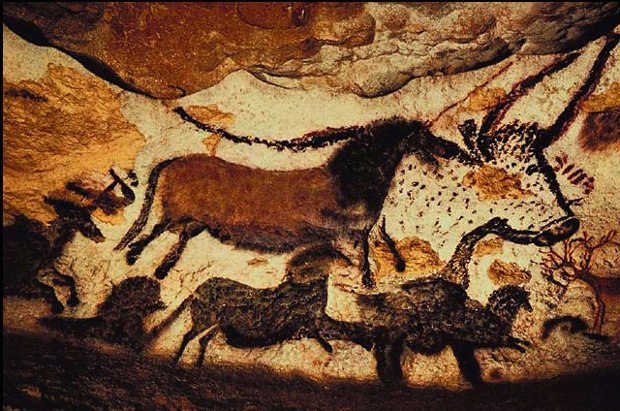

What interested me greatly about Marshack’s work was what he postulated about the cave paintings of Europe. First of all he reminds us of the weird feeling we have when inside a cave... If you've ever been inside a large cave, you'll know this feeling. And if you've ever been deep inside a cave and turned off your light, you will know what dark is! It is a total blackness and quiet we can experience in no other way, especially with the deathly feeling of being under tons of rock.

Alex Marshack pointed out that all those beautiful cave paintings we know of were mainly made in the darkest chambers, deep inside the caves. Why did those early artists want to paint in darkness when it must have been enormously difficult for them? How did they gain the skill to do that?

It proves that even so-called primitive, hunter-gatherer societies felt it important enough to feed artists, giving them time and conditions to develop their graphic sensibilities and methods, to be able to draw and paint in isolated, pitch-dark caverns! It certainly proves that they were able to produce light. Hollowed stones have been found inside the caves, which were probably oil lamps. They also had to be able to bring drawing and painting utensils deep into those caves, and wood, to make scaffolding. They needed to mix colors on the spot. Flattened areas of stone have been found with enough color residues to indicate that they were used as palettes.

But it can be assumed that they did not drag all those animals in there, to use as models! Yet these paintings are marvelous examples of drawing skill by any standard. They were trained artists! What is especially fascinating to an animator is seeing that many of the drawings were attempts to convey an image of motion!

This amazing art was created during a period of primitive and exceedingly difficult life, when merely staying alive and hunting for food was the predominate need. But yet the tribal chiefs felt it necessary to support "professional" artists! From this we have to assume that these so-called cave men had a more advanced social organization than we might have thought, and that they were able to bring in a surplus of food, and that not every man and woman needed to spend full time scrabbling for existence - that a society 35,000 years ago could support and train artists!!! But why? All of these deductions by Alexander Marshack got me to thinking that those prehistoric people had a culture and a lore they wished to preserve, to pass on - a need to tell stories!

It struck me: What more imprinting way could there have been for those people to inculcate their youth with the legends and lore of their community and tribe, than to lead them into the enveloping darkness of a cave, to a deep, forbidding gallery, always the one that was the most sound resonant, (Cave-age Surround Sound!), and in flickering oil lamp light, illuminating wondrous images, tell the tribal tales in an atmosphere of guaranteed attention. The prototype "animated movie" presentation!”

So we can see that though the technology of animation has changed a bit in the last 35,000 years, the aim is the same: to tell stories in the most dramatic, riveting, and attention-holding way we can.

Technical advancements come thick and fast in our times, but we mustn’t let them dominate our work as things unto themselves. Technology is an ever-evolving toolbox, but our use of it as filmmakers must always be the same: to tell our story! If you learn anything, learn to maintain the clarity of what you are saying, the story you are presenting. Don't fall victim to the mannerisms of the moment. Don’t allow technique to smother your story!

In our art/craft of animation, in order to truly win our audiences hearts, we should aim not just to make our characters move, but to make them live – or certainly seem to live – to project an inner life that motivates their actions, and make those actions plausible. I wish I could say that I ever truly accomplished that… but I was a UPA man at heart. I have always valued strong stories and humanity. But in animation, I had other goals, guided by graphics, symbols, and stylisation. That has its place, and my successes nicely balanced my failures… but I have grown in my understanding of what animation is all about.

Our audience is made up of humans, and we must respond to human expectations. When I first became a director, whenever I entered a studio engaged in producing films under my direction, I couldn’t escape a certain moment of panic. “My God! All these people are working on something that is my conception! What if I’m wrong? They are all trusting their livelihood to the notion that I know what I’m doing!” Well of course, I had to know what I was doing!

What does a director do? If you’ve sat through the end-credits of an animated feature film recently, you know that what we do is a (large) group effort. Perhaps you would love to think up, write, design, animate, paint, voice, shoot, compose, computerize, and edit your own film, all by yourself… Great! Maybe you will win a prize in a major festival! That is, after four to six years of work, possibly being financed by a grant, but more likely from your career as a McDonalds fry cook. But if you actually want to earn a living in animation, you will have to find your place in a studio; your place in the complex interplay of many talents.

A good animated film is a deft amalgam of many talents and crafts. But a good animated film must look like the work of one hand. And that is what a director does. The director is the one with the responsibility for the overall vision, and he or she is the one who must know what goes in, and what is discarded; the one who holds the production to a straight line. Without a director’s clear vision and firm hand, the movie will wander all over the lot.

A good animation director should basically know how to do, or at least understand the place, of all the elements of the movie, and strive to keep them all in balance, not letting any one thing dominate, and have his or her eye and ear at all times centered on the story being told, the premise being proved, and the point being made.

How to gain the confidence, the support, satisfy the egos of many diverse talents, and draw from them their best work, integrating it all into a seamless unity, is the constant endeavor and challenge of an animation director, just as much as any film director. Go for it!

- Gene Deitch

Gene is the Oscar-winning director of Munro and creator of Tom Terrific, Mighty Manfred, Nudnik and a thousand successful cartoons. You can read more about him and his truly unique and illustrious career by visiting his website, genedeitchcredits.com, his Facebook page at facebook.com/nudnikrevealed and his soon to be revised online book, How to Succeed in Animation at genedeitch.awn.com.