Lou Scheimer’s autobiographical Filmation history is a must read for anyone interested in the formative years of "Saturday Morning Cartoons."

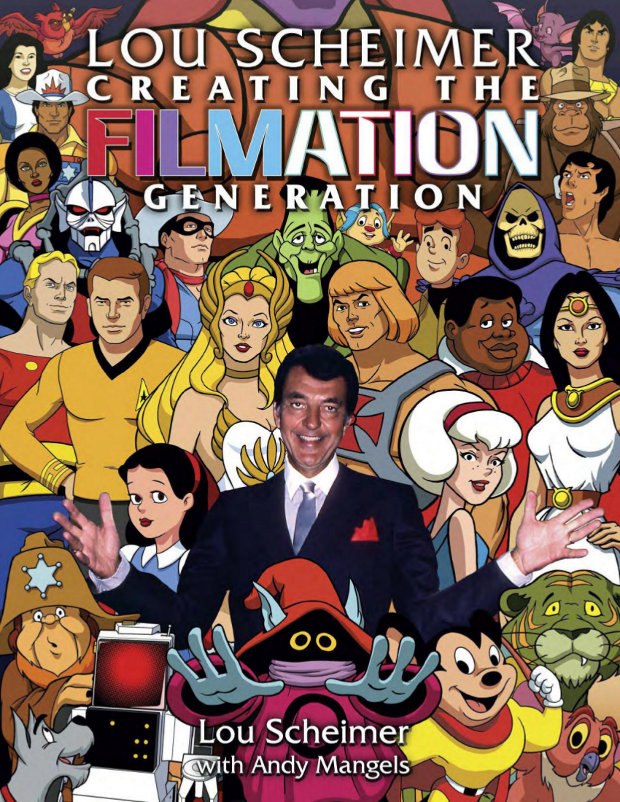

This history of Filmation Associates is an animation studio history with a difference. Most are objective histories, well documented and footnoted, by animation historians who were not personally associated with the studios. Creating the Filmation Generation is by Lou Scheimer, who co-founded Filmation and was its president for the twenty-six years of its existence. Also, it is a detailed anecdotal reminisce rather than a detailed academic history. Nevertheless, it is engrossing reading with lots of details and publicity graphics. It will satisfy all but the most demanding of animation historians.

Actually, it is Lou Scheimer’s autobiography. Most people probably won’t be interested in Lou Scheimer’s autobiography, but if Walt Disney, Chuck Jones, and other animation luminaries can have their whole lives documented, it is good that there is at least one book that covers Lou Scheimer’s origins. His earliest claim to fame was vicarious. In 1921 or ‘22 his father, who was a World War I war hero and Jewish activist in Germany at the time, punched Adolf Hitler unconscious during one of Hitler’s earliest racist beer hall diatribes in Würzburg. Hitler set his Nazi street thug bodyguards looking for Salomon Gundersheimer, who prudently immigrated to America.

Scheimer was born in Pittsburgh on October 19, 1928; joined the Army in 1946 and was honorably discharged in 1948; entered Carnegie Tech to study art; got married in 1953; and moved in 1955 with his wife Jay to Hollywood to get a job painting backgrounds in the animation industry. Scheimer’s first job was at the Kling Studio, a little commercial art company in the former Charlie Chaplin Studio. Scheimer’s art desk was in what had been Chaplin’s personal bedroom. From Kling, Scheimer went to work at Warner Bros. Animation, then after a few months moved on to the new Hanna-Barbara Studio. In 1957 Larry Harmon bought the rights to Bozo the Clown and hired Scheimer among other animators to produce a series of TV cartoons around him. It was while working for Harmon that Scheimer met Hal Sutherland, his longtime Filmation partner, and others who became the original Filmation staff. In 1960 Harmon closed his animation department and Scheimer went to work at a tiny studio, True Line, where Sutherland was already working. A couple of years later True Line got a contract to produce a TV cartoon called Rod Rocket. True Line could not handle the job, but Scheimer and Sutherland thought that they could, so they incorporated as Filmation Associates in 1962 and took over the series. Three years after that, Rod Rocket was finished and they could not get any TV animated commercial jobs. They were packing up, set to go out of business when they got a telephone call from DC Comics in NYC asking if they could produce a Superman cartoon series for CBS’ new Saturday morning Children’s TV lineup. And that is how Filmation became “the king of Saturday morning TV cartoons”, as they have been called.

“I got a phone call from Norm [Prescott, the third Filmation partner], and he said, ‘Lou, do you think we could do this series ourselves?’ I said, ‘How much are they offering?’ He said, ‘$36,000 a half hour.’ Well, I knew then that Hanna-Barbera was getting about $45,000 a half-hour for animation. I said, ‘Sure, we can do it. What the hell? We’re out of work anyway. …’ I had no idea what we could do it for, but I knew that was better than we were getting.” (p. 45)

Year by year, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968 … to 1986, 1987, 1988. Superman and Batman and Aquaman and lots of other costumed superheroes. Archie, The Groovy Goolies, the animated Star Trek, Fat Albert, Will the Real Jerry Lewis Please Sit Down, The Brady Kids, The Lone Ranger and Lassie and Tarzan and Flash Gordon and Zorro, The Secret Lives of Waldo Kitty, Blackstar and BraveStarr, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, Gilligan’s Planet. A tremendous list of shows. Filmation’s live-action TV series, and the studio’s foray into theatrical animation features. The many colorful Filmation staff members. A few risqué incidents: “Waldo Kitty was a good idea. […] It started out live-action with a cat and his girlfriend – Waldo and Felicia – and a big bulldog named Tyrone that was always after them. When Waldo would get into real trouble, and the bulldog got close to him, Waldo would imagine himself turning into one of the characters that he liked from television. […] The live-action segments were mostly filmed in and around a yard and a house, and we had to work with real animals. The cats were fine, but the problem was with the damn English bulldog. We were usually shooting him from the back because he was chasing the cat and all you could see were giant testicles! Every time he turned around, these monster balls were hanging down there, swinging back and forth. […]” (p. 118)

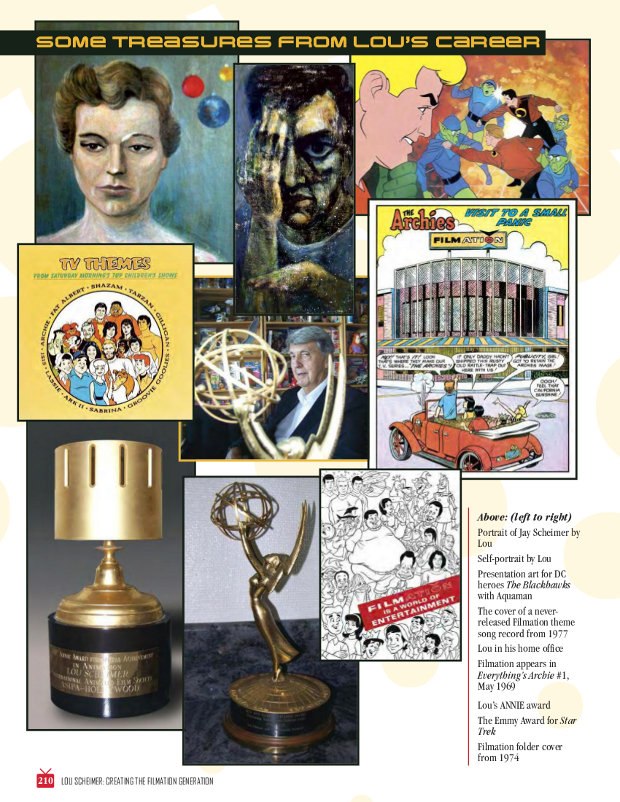

The lawsuits, labor strikes, and Scheimer’s public debates with Peggy Charren of Action for Children’s Television over her accusations of too much violence in children’s TV, and that TV cartoons were just half-hour and one-hour long commercials for their sponsors’ toys. Scheimer’s Emmy and Annie Awards. Scheimer’s increasingly desperate, public pleas within the animation industry and during the 1980s to keep animation production within the United States instead of sending it abroad to cut costs (“runaway production”).

One manner in which Scheimer’s personal narration differs from other studios’ histories is that Scheimer reveals some production costs. Other histories discuss technical aspects in detail but never reveal price tags. Another is offering personal opinions of the people with whom he dealt. Practically everyone he meets all during his career is described as a saint … a gentle soul. “Don Knotts was one of the sweetist, loveliest men in the world. (p. 250) But every so often there is someone whom he names who “is not very pleasant”.

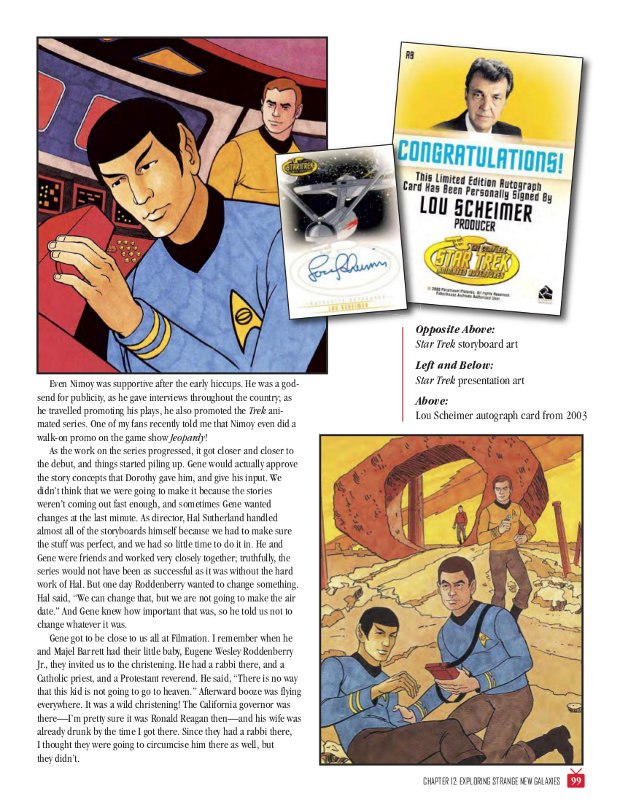

Scheimer does not directly discuss Filmation’s reputation for poor quality production, but he does not try to hide it, either. When he appeared at a Star Trek fan convention to promote Filmation’s forthcoming animated series, “… I heard a girl’s voice say, ‘I hope it doesn’t turn out like all the rest of Filmation’s sh*t!’” (p. 98) One of Filmation’s early live-action TV series was 1975’s The Ghost Busters, with two humans and a gorilla. “On our budget we couldn’t afford both an actor and a gorilla suit, so we needed to try to find an actor who owned a gorilla suit!” (p. 119) How much does it cost to rent a gorilla suit? Filmation’s Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night movie was reviewed by the Boston Herald as, “The creators at Filmation have been churning out animated garbage for 25 years, and nobody has been able to get rid of them.” (p. 251)

Presentation art and model sheet from 1973's Mission Magic! with none other than a young pre-soap opera Rick Springfield.

In 1969 Filmation was sold to the TelePrompTer Corporation; in a stock exchange. This did not affect Filmation’s operations. In 1974 Hal Sutherland left the company. In 1981 TelePrompter was acquired by the Westinghouse Electric Corp. Westinghouse left Scheimer to run Filmation as he wished, but was more obtrusive about owning the company. Early in 1987, the top management at Westinghouse changed, and Scheimer did not have a close relationship with his new bosses. In 1988 a rich French company, L’Oreal, wanted to buy Filmation from Westinghouse. Scheimer at first thought that L’Oreal was prepared to give its money to Filmation to increase its production or its quality, but he soon learned that L’Oreal was just interested in Filmation’s extensive animation library. It intended to close Filmation down and start releasing Filmation’s backlog on the new home video market. Scheimer pleaded with Westinghouse to reject the sale, or give him time to raise enough money to top L’Oreal’s offer, but on Friday, February 3, 1989, the sale went through. Filmation was closed down, and its entire staff was laid off.

This is not the end of the book. In the closing twenty pages, Scheimer tells briefly what he has been doing since 1989. He formed a new company, Lou Scheimer Productions, and developed many new proposals for television animation, but nothing sold. In 2004 he gave up and retired. “I had done presentation after presentation after presentation, and I couldn’t sell them. The office was costing a ton of money. I got to where I was really unhappy. I felt like I had wasted 15 years in semi-retirement trying to get things started again, and had not been able to be successful at it.” (p. 273) Declining health including triple bypass heart surgery was an increasing problem. But since 2004, Scheimer has found himself in increasing demand for commentaries on DVD releases of Filmation programs, and at Filmation staff reunions at fan conventions. So in a sense, Filmation still lives. At the 2012 Comic-Con International, it was announced that DreamWorks Animation was purchasing Classic Media, the current owner of the entire Filmation library. Does this mean new productions of some Filmation titles?

“Almost all of the interviews with Lou Scheimer and others for this book were conducted 2004-2012 […] (p. 287) Scheimer says that his memory has been affected by Parkinson’s disease. “While I can remember a lot of details about a lot of things, in the last five or six years, my memory has gotten far worse. Mostly what escapes me are very specific items, such as names; I can remember the events and details, or even colors or things that are said from the past, but the specific name might fail me. […] This made assembling this book a challenge for my co-author, as he had to research a lot more details than expected to make sure that none of the facts were incorrect.” (p. 280)

Scheimer, and his co-author Andy Mangels, have succeeded. This history of Filmation Associates may lack a few minor details, but between Scheimer’s memory and personal files, and Mangel’s research to fill in missing details, this is an “all that you want to know” history of the animation studio from start to finish. It is illustrated on almost every page with production and publicity art of Filmation’s titles, and with photographs from throughout Scheimer’s life for his autobiography. Filmation may not have been the most prestigious of studios, but for anyone interested in its history, or in the history of animation in “the Saturday morning years” of 1965 to 1990, Lou Scheimer: Creating the Filmation Generation will be indispensable.

--

Fred Patten has been a fan of animation since the first theatricalrerelease of Pinocchio (1945). He co-founded the first Americanfan club for Japanese anime in 1977, and was awarded the Comic-Con International's Inkpot Award in 1980 for introducing anime to American fandom. He began writing about anime for Animation WorldMagazine sinceits #5, August 1996. A major stroke in 2005 sidelined him for severalyears, but now he is back. He can be reached at fredpatten@earthlink.net(link sends e-mail).