In part one of AWNs in-depth Cars coverage, Bill Desowitz focuses on the character and lighting innovations at Pixar Animation Studios.

Dont to be fooled by the simplicity of Cars it pays homage to Miyazaki, Route 66, small towns and a code of honor. Unless otherwise noted, all images © Disney/Pixar. All rights reserved.

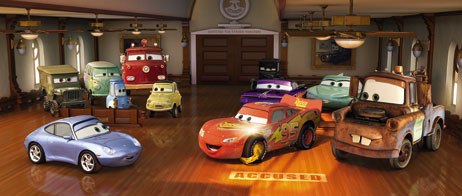

Dont be fooled by the trailers or promotional tie-ins: Theres more to Cars than meets the eye at first glance. Its deceptively simple in its animation and storytelling and the prettiest piece of 3D-animated eye candy yet so theres definitely more underneath the hood of Pixars latest animated feature (opening June 9, 2006, from Disney). In fact, theres something for everyone in John Lasseters most mature and personal pet project, in which hotshot rookie race car Lightning McQueen (Owen Wilson) finds himself unexpectedly detoured in the sleepy Route 66 town of Radiator Springs, where he encounters life lessons with a slew of off-beat characters, including Doc Hudson (Paul Newman), a 51 Hudson Hornet and the cranky town leader; Sally Carrera (Bonnie Hunt), a snazzy 2002 Porsche; and a rusty, lively tow truck named Mater (Larry the Cable Guy).

Cars is about enjoying lifes journey rather than speeding ahead to finish first (a nod to Miyazaki, to be sure); its an ode to Route 66, the Mother Road that serves as the legendary American artery connecting north to south and east to west; its a tribute to the vanishing community of small towns; it embraces the value of family and friendship; its about individual sacrifice, mentoring and respecting your elders; and childhood memories and super 8 home movies; and the thrill of NASCAR, racing movies and Paul Newman movies. (The Color of Money, anyone?) But most of all, its about Lasseters love of cars, from Hot Wheels right on up the line, and bringing them to life in the computer in that inimitable Pixar way.

Creating Cars on the Fly

After conquering humans in The Incredibles, the Pixar character animators literally had to switch gears with Cars, adopting a less is more philosophy, since, for the first time, they were forced to devise their own rules. With The Incredibles, animators had to orient their minds toward very complex models, recalls supervising animator Doug Sweetland, who concentrated on Mater. They were definitely the most complex bi-pedal models that weve ever dealt with. Then going on to Cars, all of a sudden all that extra gear we had to use got stripped away. Obviously they dont have any limbs; they dont have anything down their fingers up to shoulders or feet up to legs. In fact, the head and the body are almost the same thing, so it became this minimal exercise in how to do the most gesture with less. Similar to Finding Nemo, but only more so. We did the most amount of research of any film on Cars: Car physics and truth to materials, which was the mantra of the show, making sure they were convincing as 3,000-pound objects. But research can take you only so far until you have to figure out a language for these living cars, because theres no reference point.

Pixars artists were compelled to use their imaginations to make the cars movements and gestures fit with the design. Tire movement and steering were used for dramatic effect.

In other words, they were compelled to use their imaginations to make the movements and gestures fit with the design to achieve the fullest range of performance and emotion possible. The cars may not have arms and legs, but they could lean the tires in or out to suggest hands opening or closing in; and they could rely on steering to point to certain directions. Crucial was the design of a special eyelid and eyebrow for the windshield (inspired by the classic Disney short, Susie The Little Blue Coupe) to communicate expressiveness that cars dont have.

There were design elements, such as with the eyelids, which is a unique convention, Sweetland continues. Basically, because of the windshield, its like having two pupils in one eyeball. How do you suggest that the two pupils actually rest within two eye spaces? Eyes in windshield literally have more of a window to see into the character, particularly for the scenes with [Newmans] Hud. Johns point was if you have eyes as part of the windshield, the head and body are fused. You have to reason everything through. With the eyes, we created a language specific to this movie. Not only to delineate eyeballs but also gender too. We came up with this rule that the stare step was a guy trait and the eyelid bowing up was a girl trait. Theres no reference for this, but even in fantasy terms they have their own logic.

Inspired by the classic Disney short, Susie the Little Blue Coupe, animators designed special eyelids and eyebrows for the windshield to communicate expressiveness in the cars. © Disney.

We had to invent something on the fly based largely on the great story drawings suggesting a stare step in the middle down to multi area use of the body. Those fenders kind of feel like cheeks if you angle them up a bit so that they cradle the bottom of the pupil as it looks out, or they could be like shoulders. It really became a matter of the animators interpretation for the specific needs of the scene exactly how these different parts of a car would be designated as parts of a character. So that was definitely another challenge too. Its a tribute to the variety of movies being made at Pixar now. A lot of the guys who took to The Incredibles really easily had to struggle a bit at the beginning of Cars. They had to relearn these new rules.

Not surprisingly, there was considerable trial and error, particularly in getting the eyes just right. According to supervising td Eben Ostby, the first few times they put the eyes in the windshield they looked funny. The far eye looked like it was a different size. Perspective didnt work well with the eyes on a flat windshield. They looked distorted even though they were the projection of a round thing on a windshield. We cheated them a little bit. We had a system that would change shapes slightly to counteract the effects of perspective. It dialed down perspective, which is something we never did before. [We came up with] a solution somewhere between complete perspective and new perspective.

It took considerable trial and error to get the eyes right. Animators had to cheat the perspective so the eyes wouldnt look distorted. John Lasseter is very specific about how eyes should be illuminated in his movies.

The way John likes to see eyeballs illuminated is very specific on all his movies. He likes to have a hot spot on one side and a glow on the opposite side of the iris and that needs be driven by the light source but not slavish to the point where you take creative control away from the animators. Its a slightly cartoony feel.

A great epiphany occurred early on during testing for a character named Luigi (Tony Shalhoub), a gregarious 59 Fiat 500 that runs the local tire shop in Radiator Springs. In trying to personify Luigis gregarious nature through movement, they hit upon a way of pirouetting that opened up all sorts of opportunities for the other cars as well.

The Luigi test was done by [directing animator] Bobby Podesta, Sweetland offers. The epiphany there was youre trying to search for the line between fantasy and reality. As I was saying, with truth to materials, its about finding touchstones or details that ground this cartoon character in a reality, yet at the same time its a fantastical situation, especially in Luigis case, who is really full of life. Its funny because after you see a test like that or you see a movie, a lot of this seems self-evident. But thats the point of all of this work: you want to make it seem effortless and natural. When you really dont know the rules yet and youre feeling your way through this developmental animation, a test like that can be a beam of light that shines down. It made you take for granted that this was a living thing. Thats one of the tricks of animation: to sell that this thing really does exist. The test had the flights of fancy as well as the important aspects of weight and physics a logic that helps you understand that this is the real thing.

In this progression from Cars, view a storyboard, wireframe, animation render, occlusion, ray traced occlusion and reflection and final lighting and rendering.

For me, I always find certain gestures fascinating when you consider that they could only happen when a character has lived an entire life in this body. So one of the things I enjoyed doing was finding gestures really specific to a car [as though it were] a living thing. For instance, rocking back and forth on its wheels. Actually, it didnt end up being in the movie, but I tried some of that with Mater. I think it goes with his character because he is very comfortable in his own skin. He is one of the most natural characters in the movie or in any Pixar movie. I wanted to get a sense of his internal reality. Theres a question [here] that only animation can answer: When do they engage their brakes? There are times when they are able to move forward with gas power. But there are also times when they feel like they are able to manually roll their own wheels. And there are other times when they can obviously release their wheels and just coast. So these are the kinds of opportunities that animation can provide.

Director John Lasseter (left) sees limitations as opportunities and urged truth to materials to supervising td Eben Ostby (center), supervising animator Doug Sweetland and the rest of the team.

In terms of Lightning McQueen (an homage to the late Pixar animator and car enthusiast Glenn McQueen), they looked more to sports figures than Steve McQueen for inspiration: Tiger Woods, Joe Namath, Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan. It was important to stress amazing natural talent and tremendous ego. They played up his obnoxiousness and extraordinary flights of fancy in another Miyazaki nod.

A lot of this came from John, Sweetland continues. One of the things he kept talking about was truth to materials, which we were betraying left and right before production. Just dont bend the cars too much. Obviously we understand their suspension the undercarriage of the car so you can have a lot of leeway there as far as making gestures, but this is not a squash-and-stretch show, which is another reason why a lot of animators mightve thought that their hands had been tied after The Incredibles. Again, it becomes more of a finesse game and you find new solutions or you find that you dont have to do so much with gestures. In one case, Huds bumper is chrome and its one of the most highly reflective elements in the movie. And you can see the whole world reflected in this object. The more it bends around, the more it looks like a noodle. Its a really highly sensitive area. And [in many respects], hes the emotional center of the movie. We looked at Paul Newman from Color of Money and Nobodys Fool, and it made sense to keep the bumper pretty immobile because Newman doesnt move his mouth that much. So he has a certain gravity that he lends to a scene [because of his talent and stature], which satisfied a technical need as well as a creative one. But I dont know if we wouldve arrived at that decision without this limitation. And John is the first one to say that limitations are opportunities.

RenderMan was used to create the reflections in the car paint. The accuracy of the reflections was very important and revealed how well the cars are put together.

Innovative Ray Tracing Was Key

The goal on Cars was to also push the visuals further than ever before, which could not have been achieved without advancing ray tracing at Pixar. We were essentially early users of the ray tracing capabilities that the RenderMan group has put into the renderer, Ostby explains. We used them in a lot of different ways to do three or four primary things that we couldnt do before or were hard to do. The most obvious thing for car paint is that it needs to have reflections and the accuracy of reflections is very important. For instance, you can see eyes reflecting in a hood. This is a vital cue. Other things that seem subtle show how well a car is put together. An example of that is when you have a shiny chrome trim ring around a headlight, theres a little bit of reflection back and forth where the ring hits the body and tells you that its really sitting on the body and not floating out in front of it. Without those reflections, it doesnt appear like its the same piece.

Plus, the reflections of the world around the car couldve been done with older, simpler technologies. But some of the reflections really needed ray tracing. Something else thats very important in terms of the realistic look that were after is ambient occlusion. Its the way the corner of things get darker, essentially: the little cracks and crevices and areas that have a broad shadow thats ambient occlusion, which uses ray tracing to figure out how much of the light coming from all directions impinges on a particular spot. So characters that are not terribly reflective, such as Mater, get a lot from that: it makes them feel richer. Where ambient occlusion is really critical for us is a CG shadow. We noticed that one of the things that made a car feel real in the open sun is that the shadows underneath are inconsistent, theyre not as dark along the edge as in the middle, so we got that with a combination of occlusion and shadowing.

A further lighting technique used on Cars was radiance, which is primarily the color light spill from one object onto another. When McQueen drives along the racetrack, a reddish puddle of light thats mixed into the shadow is an example of radiance.

A lighting technique used on Cars was radiance, which is primarily the color light spill from one object onto another. An example is seen in the reddish puddle of light mixed into McQueens shadow.

One of the biggest tasks was being able to accomplish all of the expanded lighting techniques while cutting down on the render time, which, early on, approached 17 hours per frame. We instrumented a lot of what we did with statistics so we could glance at the numbers and figure out if we were doing what we should be doing and to catch our mistakes, Ostby adds. Say we had an object that was using ray tracing for shadows. If we knew that the whole world was looking to the car for shadows, it could be expensive. But if you could limit that to just one road, you could simplify things dramatically, particularly when you have the vegetation that we had, which contains a lot of detail. So we wanted to make sure that the part of the ground that was checking for information from plants was doing so only from plants in its neighborhood.

We reengineered our lighting pipeline in a couple of ways. The primary thing was we wrote a new tool for ourselves for the setting up lights, which made it possible to deal with the complexity of light sources and all the things doing ray tracing. We put those controls in the hands of the lighting team. We also reengineered the way we construct low level lighting so we could hook together different parts of a light and make it more powerful and modular, so a light could do both shadowing and occlusion. One of the highlights with a lot of eye candy value is the neon sequence. There we had to do a lot to make it look lovely, primarily to get the sense of light emanating from all along the neon tubes. For that we needed light sources that werent just point sources but were areas all along the tube casting spill along the buildings and along the ground. Of course, the tubes themselves had to glow and there were dirt and dust on the tubes. Plus for all the characters that were reflecting those neon lights, we wanted the neon to reflect off a particular body panel. So there was a lot of cheating of light source location so it would read just right and tell the story that we wanted to tell.

Pixar created the tool Ground Locking just for Cars. It allowed the animators to lock the wheels to the ground but give the car real suspension and bounce.

Besides lighting, Pixar created a whole new set of other tools for Cars. One was Ground Locking. We wanted to help the animators concentrate on the expressions of the cars, Ostby continues. Shoulder motion, head motion. So we made the cars automatically stick to the ground. This was new to us. We could make the wheels lock to the ground and roll, and then make the body position dependent on that as if there were springs and a real suspension in there. As a result, the cars were already where they needed to be and all we needed to do was add something special. The car would react to bumps in a realistic way. Certain cars had a bouncier suspension than others.

The Kingpin system allowed cars to behave in a realistic way, including all the secondary motion involving wheels, suspension, springs and antenna.

Universal Rig was the technology behind the character rigging setup. That was a single character that the animators liked to work with, and we found a way of applying those central controls to other characters. So all the characters worked essentially the same way. This made it easier to build them.

The animators did a lot of tests and dialed in how bendable the car should be without throwing you out of the movie. You dont want rubbery looking cars or have them be too hard looking so you lose expression. After a short while, you realize its like a persons face where its not too elastic and theres a sense of structure there.

Sweetland, meanwhile, says Cars is all about creating fantasies within a believable, naturalistic world its why the movie lends itself so well to the computer animation medium.

Bill Desowitz is editor of VFXWorld.