Joe Strikes goes back to school with an indie master.

The latest crop of students learned the nuts and bolts in Plympton's School of Animation. All images courtesy of Joe Strike.

It might not be the equivalent of studying under Rembrandt or da Vinci -- but in terms of animation, it's pretty darn close.

It's Jan. 18th and the second iteration of Bill Plympton's School of Animation is underway. Under his tutelage and in his studio, 11 students are learning the nuts and bolts of what goes into creating a cartoon -- and how to make sure money comes out of them.

Speaking of which, what motivated Plympton to offer the course? "Money -- I was really broke this summer. I almost had to leave this space," he says, referring to Plymptoons' home, a compact West Side Manhattan loft where the course is taking place. "Everybody [on his staff] complained "about a possible move, "so, I said, 'OK, I'll teach a class.'

"I've been doing lectures, master classes for a long time, I used to do summer animation classes --it didn't pay very well and it was a lot of work. It's more comfortable for me to do it here in my studio and do it at my own pace, my own schedule."

Tuition for the 10-week, two-hour course is $1,200: a hefty-sounding sum, perhaps, but one that works out to $60 an hour -- a pittance to learn from one of the superstars of the independent animation world. "It's the second time I'm teaching the course here. We have some people who were here the last time, so I'm trying to vary it a little bit."

Plympton's goal for his pupils: create a 30- second cartoon (the class ended March 22). Things get rolling with a getting-to-know-you session, as his students introduce themselves, show samples of their work and explain why they were there. People with illustration or animation experience already under their belt seem to predominate, including a Massachusetts college animation instructor, A Scanner Darkly assistant animator, an animation studio production assistant, a documentarian who was part of the legendary Yellow Ball animation workshop in his childhood, a French CGI producer eager to go hands-on in classic 2D and the president of New York's Society of Illustrators.

"I heard about the course and I had the knee jerk reaction that I had to do it," explains Dennis Dittrich, the Society's head and an illustration instructor at New Jersey City University. "I figured I'd grab it while I could. Bill is an amazing draftsman and he's a draftsman who can make his work dance. Who's gonna say no thanks?"

Scanner Darkly animator Blue Bliss is hoping "some of Bill's magic rubs off on me. I want to come away from this class conceptualizing short, snappy ideas that end with a bang and really work. My ideas tend to run towards David Lynch and Werner Herzog -- long, grim, deep-meaningful things, so I need to work on my humor."

Skip Wrightson, the New England animation instructor, first studied the medium in 2005 at the Vancouver Film School. Soon afterward, he found himself "lured to Los Angeles by a job at JibJab that, unfortunately, wasn't there by the time I drove from Cape Cod to California. They had shelved a large scale production of a direct to internet Flash-animated feature about a monkey's first day at school.

"I worked at some small post production houses and I briefly volunteered at ASIFA Hollywood hoping to get in with the John K[ricfalusi] crowd -- the closest I got was thumbing through almost every original Ren & Stimpy storyboard. Last year I wrecked my VW and signed up for Bill's workshop with the insurance money. It seemed like a great opportunity to meet folks in the New York animation/illustration community and get some feedback from one of the masters of independent animation. I'd like to have a studio like Bill's someday."

Early in the evening, Plympton shows the class a work in progress: The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger, the story of a deluded bovine who almost gets her wish. Plympton asks for feedback on the cartoon's ending, a payoff gag that doesn't quite read. "I know we have some problems with it… like all my films, it doesn't have an ending yet. I think it's really important that you get feedback on your film before it's finished. You work on it for so long, you're so involved with the character you can't see it with fresh eyes anymore. Nothing's worse than going to a film festival and a joke you thought was really going to be great falls flat, nobody laughs. You realize what you should have done but now it's too late --you've spent thousands of dollars on prints."

After a brief glance at his production techniques -- keeping a cartoon's art organized in scene folders, explaining exposure sheets and separating elements in a shot onto different levels ("anything that moves gets its own level"), Plympton talks about brainstorming: "A good idea is half your film right there --I've seen badly animated films that were great because they had a great concept." He points to two file cabinet drawers "filled with ideas -- anytime you get an idea, just jot it down. That's why I like New York City; you see so many different kinds of people that spark ideas."

Plympton screens his Oscar-nominated Guard Dog film, explaining "it was inspired by a walk through the park and seeing a dog barking at a bird." Wondering how a dog could see a small bird as a menace to its master led to the film's series of nightmarish "what if" scenarios, with the paranoid pooch seeing danger at every turn. ("People love the dog," he explains the following week, as he quickly sketches out ideas on a large newsprint pad for the canine's next film that won't be revealed here. "These are terrible drawings" he mutters. "I cannot do a pitch-- that's why I can never do television. The thrust of the dog films is that he's looking for love, looking for acceptance... and never getting it.")

According to Plympton, the formula for a successful short film is "a strong beginning, strong characters, humor and a big finish." He asks the class to come in next week with ideas for their 30-second films, "the simpler the better, with one or two characters and a gag at the end." Wrapping things up for the night, Plympton talks about his influences, beginning with a childhood in the Oregon woods where "there wasn't a lot of culture," but plenty of Warner Bros. and Disney cartoons on TV. The toons led him away from the fine arts and into animation. "Paintings don't have humor. Animation is universal; you get to show it to everybody. I want to make people laugh with my art."

Plympton fills a sheet and a half of that newsprint pad listing other artists who've influenced his work, from Milton Glaser to Robert Crumb to Charles Addams ("the first guy to make sick humor popular… that was very revolutionary in the 1930s") to Winsor McCay, Miyazaki, John Kricfalusi, "the Pixar guys," Jacques Tati, Oscar Grillo, Nick Park… and, as they used to say, many more. "I could go on for three more pages," Plympton admits before ending the first week's class.

A week later Plympton, beach sandals on his feet, explains storyboarding to the class ("the place where your film comes to life -- the more detailed, the better your film will move along") before asking to hear his students' cartoon concepts: Illustrator Tom Cushwa wants to do a follow-up to his Edison vs. Tesla cartoon he screened last week, praised by Plympton for its "great colors and good timing… a good job making Tesla's head spin --that's hard to do." The next student presents a storyboarded vignette of a woman reflecting on her divorce. "What's her motivation?" Plympton asks. "You could do this in live action. Make it more magical, more animated." The ideas continue: mothers and daughters…city life is tough…a cat and a cuckoo clock…a guy wearing too-tight shoes…Bliss presents a pair of animal con artists, Ticket Ted and Toad (inspired by an airport warning that illegally parked cars "will be ticketed and towed")… a commercial for Dietrich's New Jersey college… a commercial for a church…a music video that doesn't have a song yet…an explosive soda bottle that leads to unforeseen consequences… a lesson in counting to a billion…

Plympton asks the students to come to next week's session with their chosen idea storyboarded out. In the remaining weeks the class will focus on both the technical aspects of animation production (layouts, pencil tests, timing, visual and sound effects and music) and the business end of the medium: real-world, need-to-know information on budgeting, publicity, promotion and distribution that most art school and university animation programs never quite get around to covering. (Plympton's long-time producer John Holderried will cover the ins and outs of copyrights, comic conventions, festivals and internet screenings.)

It's March 29th, and the last session of Plympton's animation class (extended by a week to due to an out-of-town trip on Bill's part) has begun. Back in January he had hopes of seeing more completed films from his students than in his previous go-round teaching the class. "Only four or five people finished their cartoons," he said at the time. "They varied in quality, they were all good, but I was disappointed: there were three or four artists in there who were quite good, and for some reason they didn't get it together to get their films done. I was very disappointed because I wanted to see what they could do. I thought they were really talented and would produce something excellent."

Once again only five films were ready for screening, several of them still in mid-production. If Plympton is disappointed he doesn't show it; he's well aware his students have career and personal obligations outside the classroom.

Skip Wrightson has followed through on his original idea: a bottle of Fizzy Beverage contains far more kick than the person drinking it was ready for. The pause between cause and effect is nicely timed, and Plympton suggests a few gags and sound effects to push the comedy further. Blue Bliss' Ticket Ted and Toad will have to wait until another day to pull their scams on the unsuspecting; instead she presents Hell's Kitchen, a vignette of a satanic chef cooking up body parts (including a hand still clutching its iPhone) and a frying pan full of eyeballs. Rich Pickens' Bard None depicts Shakespeare as being a little too picky for his own good in seeking divine inspiration, and winding up resembling poor Yorick for his troubles. Katie Smith's work in progress features a pair of mischievous kids at the lunch table. Lydie Greco's naughty knitting granny has her eye on a handsome jogger, and, in Pick Me!, Ashanti Freeman's frustrated schoolgirl takes extreme measures to make sure she's noticed by her teacher.

As the class draws to its close, Plympton offers quick lessons in creating a complex walk cycle as viewed from an overhead angle, avoiding unwanted strobing effects when artwork travels laterally through the frame (the secret: soft edges to the artwork in question). He screens some of his earliest work, including the madly mutating singer of Your Face and his very first animation, an R.O. Blechman- inspired college effort starring a pair of larged-shnozzed characters drawn as outlines. ("I was really into Blechman at the time…my timing was terrible and I broke the 'big nose' rule.")

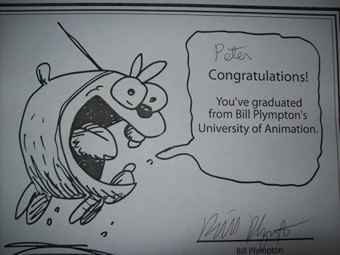

Plympton rewards the creators of the screened films with their choice of the large sized sketches created in the course of teaching the evening's class. Bill Plympton's School of Animation may be over for the moment, but he asks everyone to complete their projects and let him see them when they are done. Will they do so? As he remarked at the outset of the course, "Ambition is a large part of someone's success; if you have no ambition you probably won't succeed."

Joe Strike has written about animation for AWN, New York DailyNews, Newsday and New York Press He is currently teaching Mass Communications at New York's St. John's University and hosting "Interview With An Animator" at Pratt Institute.