How a new crop of international co-productions is changing the Italian animation industry. Russell Bekins lays down the rules for success.

Obeying the Rules

Those in the know recognize that Italy possesses a series of emerging cartoon studios who pull their weight in top-level television co-productions with countries across the European market. They may even understand that there is a startling amount of artistic talent and business savvy emerging from Turin, Rome, Pisa, Florence and Milan. What few seem to realize is that the market is maturing thanks to the very dynamic of co-production. A new crop of co-productions speaks not just to the volume of this market, but how the skills honed in co-productions have changed and matured the Italian market and created a new variety of partners and types of productions.

The growing animation market in Italy is maturing thanks to co-production, which has created a new variety of partners and types of productions. Courtesy of iStock.

Rule 1: Stare reality in the face.

"Co-production is a necessity. The costs are high, and one country cannot absorb them all," veteran producer Giovanna Milano asserts bluntly, assessing the European market.

Rule 2: Drop your stereotypes by the door.

When one speaks of Italian cartoon co-productions, impish wags from the left side of the ditch are prone to giggle over the image of perhaps a Joe Pesci cartoon goombah making an offer you can't refuse. The fact that most Americans retain a view of Italy which is part Dean Martin (who couldn't even sing in Italian without an American accent) and part Godfather trilogy does not help matters. For those who still retain these images, here's a piece of advice: get a passport.

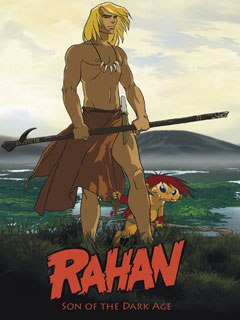

"It's better to junk your stereotypes from the start. If you are doing co-productions you have to be open-minded," shrugs Milano, who produces the Italian-French TV series Rahan, now completing preproduction. An Italian working in France, Milano has been head of distribution at Tele Images and CEO of France Animation. She is an example of the breed of co-producer comfortable in multiple countries and production situations, and intimately familiar with the needs of broadcasters in both countries with which she is associated.

Based on a French comic strip, Rahan recounts the adventures of a virtuous boy growing up in a prehistoric period of tension between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. She brought the Xilam project to Italy and RAI as a no-brainer, especially with Pascal Morelli (Corto Maltese) on board to direct. "Giovanna Milano brought up a whole generation of graphic and technical talent when she was head of France Animation," says Anita Romanelli, project manager for RAI Fiction. She has recently founded Turin-based Castelrosso Films as her pied-a-terre in Italy.

The Italian-French TV series Rahan, now in pre-production, is based on a French comic strip about a virtuous boy growing up in a prehistoric period of tension between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. © Xilam Animation/Castelrosso Films.

Rule 3: Find out what the broadcasters are looking for.

"The market has made giant steps," enthuses Luca Milano, head of marketing and animation at RAI Fiction. "The level of artistic talent is now impressive." As to the stereotype that Italian companies have "artistic delays," Milano rolls his eyes. "Ninety-five percent of our projects arrive on time or, if late, the delay is minimal. Sometimes delivery occurs even before the due date."

The Italian cartoon market has been nurtured principally by the decision by RAI to begin investing in animation in the 1990s. "We contribute around an average of 35 percent of the budget for new productions, leaving the producer to find other investors," explains Milano. This offers a strong incentive for companies from other countries to bring their projects to Italy, as well as for others to pay attention to Italian proposals.

Ah, but here's the rub: RAI will often ask for Italian artistic participation, including a co-director to go with the Italian co-producer, even for their minority stake. While this often rankles, most figure it is worth the price. "Because of the long relationship with Italian studios, sharing copyright and profits is worth it," shrugs Ellipsanime producer Robert Rea.

Rule 4: Take it to the market.

The standard path to success has been to bring a project to RAI, get their blessing, and take it on to Cartoon Forum, MIPCOM and other venues, where one tries to catch the eye of a broadcaster or production partner in another country. Along the way, Italian companies began to learn about how other countries did business.

"The first time I took a project to Cartoon Forum, I pitched to an empty room," laughs director Giuseppe Laganà, whose Everybody Loves a Moose! project with British Cosgrove Hall is now finishing its pilot phase. "The next year I took two projects. Nothing. Finally the third year I had learned: I took Lupo Alberto and we had a series." Lesson: For European co-productions, it helps to have a popular product already in print.

The confrontation with the market allows for a healthy development of the project itself. Luca de Crescenza, head of Florence-based Stranemani, just returned from pitching his preschool project Glu Glu to a packed house at Cartoon Forum. He found a lot of enthusiasm, but also a series of demands he had not considered, such as stretching the five-minute show to seven minutes to suit the British market.

This process of mixing it up leads to relationships that cross borders and form the first level of trust essential for co-productions. "We look for partners with whom we have worked before, or with a spirit similar to ours," says Stefania Raimondi, President of Turin-based Enanimation. Raimondi is co-producing Me, Myself and the Others, a fantasy series about a jumpy group of problematic jungle animals confronting decidedly human situations, loosely based on the artwork of legendary Italian illustrator Andrea Pazienza. Their partner is Germany's Motion Works, as well as the Italian studio Motus.

Rule 5: Spend more time in preproduction ironing out the details.

Producers stress the importance of such things as production schedules and responsibility for deliverables. French producer Robert Rea is also a fanatic for a "big" preproduction, stressing the importance of the modelization setup. "But after that you save time," he affirms. This is seconded by Giovanna Milano, who underlines the importance of finishing the literary and graphic bible and at least six screenplays before moving on. "You need your railways well aligned from the start," she says, evoking a train metaphor. Street Football producer Giorgio Welter of French Teleimages is even more emphatic: "You need at least a year before you can begin production."

Me, Myself and the Others, a fantasy series about a group of jungle animals confronting human situations, is the product of an Italian-German co-production. © RAI Fiction-Enanimation-Motus-Motionworks.

"The hardest part is the very beginning," agrees Gianluca Bellomo, whose Rome-based Cartoon One is now finishing work on the horror comedy School for Vampires. Their partner is German Hahn Studio, which has the majority stake and the artistic lead in the project under Gerhard Hahn. "It's important to agree who controls production flow, direction, story, and storyboard. It's vital to take at least a month to divide the work."

Cartoon One has 36 percent of the production, including model pack, storyboard, animation, and music by Angelo Poggi. Gerhard Hahn has been quick to praise their work. "In a situation where everybody is complaining, I found Gianluca Bellomo's no-problem attitude very encouraging," he asserts. "Cartoon One was definitely the right choice." Bellomo is quick to return the compliment. "We have learned a great deal from them," he affirms. "Cartoon One has grown, thanks to Hahn Film."

Well, that proves that co-production partners can like each other.

Rule 6: Know your partner.

Pisa-based Toposodo/Fulmini & Leopardi worked first with Ellipsanime as an animation service for Potlatch. "This started our relationship of co-production, which has become closer over time," states Topisodo partner Marco Bigliazzi. Ellipsanime producer Roberto Rea was also enthusiastic. "They have a good culture of the cartoon," he says, adding that their artistic contributions on Potlatch helped immeasurably to improve the series.

Toposodo then took their project Birds Band to Rea and Ellipsanime and they began to develop it together, with RAI's blessing and contributions. The series relates the adventures of a group of feathered friends who live on a dirigible and scour the globe in search of animals in crisis. "The project evolved, characters were refined," Bigliazzi relates. "Peggy the Penguin was added, even though flightless, as was Nat the Bat, who is decidedly a mammal."

Rome-based Cartoon One is now finishing the horror comedy School for Vampires. Germany's Hahn Studio holds the majority stake and the artistic lead in the project. © Hahn Film AG/Cartoon One S.r.l./ARD/RAI-Fiction.

"The French animation industry is far more developed than that of Italy," Bigliazzi adds. "But culturally speaking we are very similar... This is very important for stories, but also for the acting of the characters, and allows a closer creative and production process between the two countries."

Well, I guess they like each other too.

Rule 7: Make a mutual decision about the tools you are going to use.

"While everything is so new for each production, the basic process is always the same," Rea insists, but in the same breath is adamant about the need for partners to sit down and agree on their tools beforehand. "Do we need a new release of this software? Sometimes you don't need it."

Evelina Poggi, director of production for DeMas Partners, is now collaborating on the second series of Street Football with Teleimages of France. The series, in which orphan kids win the world cup of street soccer, was a smash hit especially in France. Evelina's company De Mas and Partners confronted several cultural obstacles at the start of production. "Every country has its own way of working," she asserts. "In Italy we work in digital, while the French tend to use paper. We settled on drawings on paper colored in digital for the model pack." She also credits liberal use of ftp for document exchanges.

Teleimages producer Giorgio Welter agrees that there were perplexities in preproduction. "It was tough at first," he admits, "but now we love each other."

Ahem.

Rule 8: Make sure you are selling the same project.

"Every producer has to sell the same product," insists Giovana Milano. Partners in different countries need to agree on how to present their project to the broadcasters. "You can get in trouble sometimes if you have two broadcasters who have a different vision of the show," adds Robert Rea. Horror stories abound of networks demanding changes in order to sell the show to a demographic for which it was never intended. "It sometimes happens that there is tension [between broadcasters] in Germany and France," Rea adds with that insouciance for which the French are famous.

Toposodo took its project Birds Band to previous partner Ellipsanime and they developed it together, with RAI's blessing and contributions. © 2007 -Ellipsanime/Toposodo/RAI-Fiction.

Rule 9: The contract should be balanced so that the partners will be able to sustain the effort over the period of the production.

While the businessman seeks to make the best deal possible for the good of his company, the artists working under him (or her) need the reassurance that their partners will be motivated to keep up the pace and deliver quality product. "There is a myth that the contract is a thing you negotiate, throw in a drawer and forget about," laughs Richard Trigona, CEO of Trion Pictures and co-developer with Colin Davis of Everybody Loves a Moose, a co-production of Trion, RAI Fiction and Cosgrove Hall. "You have to be careful to define the respective roles of management and artistic direction."

"From the middle of the project onwards, there is always a fatigue that sets in," Enanimation's Stefania Raimondi reminds us, implying that the quality of the work will suffer if there is not sufficient motivation for one party or the other to keep digging down and churning it out.

Rule 10: Find a language in common.

Rea says the common language of productions is "animated pidgin" English. It helps to be bilingual, if not trilingual. Rea, Giovanna Milano and Giorgio Welter are at a distinct advantage because they slip easily from one language to the other. Scripts, by the way, are written in English, French, Italian and whatever language the partner speaks.

Rule 11: Work with a company that is equivalent in size to your own.

This rule comes from Stefania Raimondi. Her company of 40 may be small by American standards, but it is an exception in the Italian market because they made a choice to hire all of their employees full-time instead of outsourcing their work (see the next rule). "It is important for us to work with companies of similar size because our problems will be similar," she asserts. Their partner, Motion Works, is indeed about that size.

Rule 12: Know your own team.

See above.

Rainbow Entertainment, which owns the Winx Club franchise, is the first international success story to emerge from Italy recently. It has two new series, including the horror comedy Monster Allergy (above). © Warner Bros. Ent. Inc.

Rule 13: Seek the solution, not the guilty parties.

"For us," Raimondi asserts, "it is always important to seek the result when we are working, to find the solution. There are always problems, but it is important not to automatically seek out who is wrong when there is work to be done."

Rule 14: Travel often and spend time at each other's facilities.

"I spent most of my life on planes going to Asia," Robert Rea comments grimly. "Seoul in winter is not pleasant." He is therefore sanguine about finding partners in Europe with whom to share not just one production, but even a slate of productions.

Rea is clear that one of the most important factors in a relationship is frequent meetings in each other's studios. "[Topsodo] came once a month to Paris for a production meeting," he affirms, "and we went once a month to Pisa. It's just a one-hour flight."

Rule 15: One partner must always have final say.

Both contract law and good business practice reaffirm the fact that the partner who has the majority stake has the final say. This is often moot, however, when artists get together and feel passionately about their product. "You have to look at the budget," says Giorgio Welter. "The majority partner must guide the project, and this must be understood from the beginning." This said, Welter is still a great supporter of the "right of the word." "The real rule is to talk, talk, talk," he smiles. "When one is in the middle of a free creative process, it's normal to argue."

Rule 16: Seek opportunities in the changing landscape.

Rainbow Entertainment is the first international success story to emerge from Italy in recent years. Driven by the power of its Winx Club franchise, Rainbow is about to go public, boasting that the fairy-dusted television series now in its third season has grossed over a billion dollars in licensing fees. With two new series, horror comedy Monster Allergy and the action-adventure Huntik, they are moving ahead to conquer new TV markets. Perhaps the most surprising development, however, will be the December premiere of the feature Winx Club: The Secret of the Lost Kingdom. It will be the first time in years that a highly-sought-after animation product will premiere in Italy before America.

There is also a new division of labor in the Italian market. Production companies such as Atlantyca Entertainment are driven more by the literary properties and licenses they control than the need to keep a cartoon studio running. With the fantastic success of their children's book series Geronimo Stilton, Atlantyca is now starting work on a TV series, and is looking across the pond for top-level name directors in order to assure a ready market in the states. This is good news for Italian studios, which can continue to supplement their income with services to these production companies and the projects they generate. Indeed, leading producer Enarmonia has divided its work now between its studio, which continues to do service work, and its production company Enanimazione, as has production company Toposodo with its studio Fulmini e Leopardi.

There are also signs that Italian companies are poaching in domains where they never would have gone previously. The upcoming Spike Girls, based on the world of volleyball, may well be a co-production involving partners from Asia.

Often production companies are driven by the literary properties and licenses they control. Atlantyca Entertainment is using its successful children's book series Geronimo Stilton as a basis for a TV series. © Atlantyca Entertainment.

On a corporate level, the climate is also changing. Martin Mystery was an Italian comic that Marathon produced in France and RAI helped finance. Now the Italian publishing giant De Agostini has bought French Marathon Media, and the rights to Martin Mystery along with it. So it appears that, in the name of globalization, what was originally Italian is returning to Italy as an international product.

Street Football producer Giorgio Welter, an expatriate Italian working in France, is perhaps the most passionate when he talks about the changes occurring on the Italian scene. "In the space of three years, everything has changed," he marvels. "The proposals coming from Italy are more beautiful, more interesting. They have understood the French, European market, the international system and are making giant steps. I think in another four years their projects will be the most fascinating and creative ones on the market."

Rule 17:And, above all, listen to mamma RAI.

Each of the production teams has universal praise for RAI's leadership team of Luca Milano, Anita Romanelli at RAI Fiction, and Claudia Sasso at RAI 2. Aiming at quality, they have not shied away from financing projects that have no Italian partners, as is the case with the Spanish TV series of The Invisible Man.

Giorgio Welter recounts that the second season of their very successful Street Football was held up when Rai Fiction's Anita Romanelli insisted that they make changes. After their orphan heroes won the world championship of street football (soccer) in the first season, the new season was supposed to be based on the same premise. Romanelli insisted that they instead focus on a strong antagonist who puts their sportsmanship to the test. "At the time I was not happy at all," Welter recounts. In time, he acknowledged that this was the right choice. "Now I'm happy," he smiles. "That's co-production."

Russell Bekins has served time in story and project development for Creative Artists Agency and Disney. He now lives in Bologna, Italy, where he specializes in concept design for theme park, aquarium and museum installations.