Dr. Toon discusses why Disney’s award-winning short Paperman is more than it seems.

When Disney’s Paperman won an Academy Award this past month (the studio’s first win for an animated short since 1969), Disney had more to celebrate than simply copping a gold statue. The studio also rejoiced over a wedding. You may think you know where this column is going: an analysis of how 2D and 3D animation wedded through use of the innovative Meander program developed by Brian Whited. Actually, that is only one facet of the story.

Although the animation technique is indeed a fascinating subject, the use of “vector-based drawing implements” and “final line advection” underwent exhaustive discussion in countless other articles, including an excellent one by Dan Sarto on this website. I assume that readers on this website already understand how the short was constructed and how unique the results of Meander-ing truly were. What I really want to discuss in this column is how many vectors (not the drawn type) converged to produce a historic short.

We begin by revisiting an earlier Disney film, Tangled. The last hurrah of master animator Glen Keane was a source of inspiration to future Paperman director John Kahrs, who came to appreciate the artistry of hand-drawn animation during an age when no one but students and independents used it any longer. It was common expectation during the past decade that any animated feature released would consist of CGI. Disney itself declared that The Princess and the Frog would be the last 2D film the company would produce for the foreseeable future. If there had truly been a battle between the two technologies, 2D seemed to be the verifiable loser.

That was, until Whited’s Meander program married 2D and digital by allowing animators to draw and revise artwork by hand over characters and backgrounds first digitally created. The resultant blend of animation was bandied back and forth between a CGI and a 2D team until a startling hybrid of the two emerged.

As much as Paperman looks like a hand-drawn film, one can easily discern the digital base underlying it, and the effect is uncanny. As Kahrs put it, “For 2D to be revitalized, you have to figure out a way to make it new again.” One Academy Award and countless other accolades later, it is safe to say that goal was reached in full. Yet, that is only one marriage. The second was the union of technology and capital.

The total production costs of Paperman are not readily available, and to them we must add the costs of promotion and publicity. Considering that the film was in production for at least a year (fourteen months by some accounts) and utilized novel technologies, it is quite probable that Paperman is the most expensive short in animation history. Although those in the industry could make some educated guesses, it really doesn’t matter; what does is that only a corporation like Disney had the financial resources to invest in such a film.

While Paperman was in production and later making its debut at the Annecy Animation Festival, DreamWorks animation was planning and executing extensive layoffs. 350 of 2,200 employees are slated to be cut by December of 2013. Some of it was the toll of having Rise of the Guardians (2012) flop, some of it having to do with postponing other films. DreamWorks animation may eventually recover, but it is almost certain that they could not have spent a year and (possibly) millions on an animated short. Thus, the marriage of capital and technology counted for as much as the marriage of 2D and 3D hybridization in Paperman’s success.

Yet another union had to occur in order for Paperman to become a historic short. The hybrid animation style had to click with audiences. New technologies sometimes don’t; early use of motion-capture animation came close to violating the well-known “uncanny valley” effect. Many critics, reviewers, and audiences, for example, considered The Polar Express (2004) more eerie and creepy than entertaining. Nearly twenty years after Toy Story (1995) however, conventional CGI features were no longer a novelty, either.

On the other hand, as Kahrs noted, 2D animated features needed some sort of revitalization if they were to click with modern audiences. To continue the wedding analogy, for jaded moviegoers Paperman was a beautiful new bride in the right place at the right time. It looks like hand-drawn animation fused with the realism of CGI, and filmgoers were stunned. Like most successful experiments, the outcome was highly desirable and appreciated.

Finally, there was the marriage of story and audience. It is no accident that Paperman takes place in the analog days of the 1940s.This venue allows antique charm to merge with high-tech presentation. Paperman is thus a hybrid short in many ways; it was this combination, as much as the 2D/3D meld, that gave this short further appeal. The story follows the classic boy-meets-girl, boy-loses girl, boy-gets girl prevalent in films of that era, compacted into seven minutes.

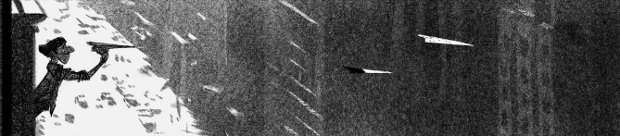

Paperman does require considerable suspension of disbelief; its internal contradictions are perhaps the film’s lone weak point. If the squadron of paper airplanes George launches are secretly in Dan Cupid’s service, why can’t at least one make its way through the office window across the street? Not only could these planes not hit the broad side of a barn, they couldn’t even (to use the vernacular of the day) land in a barn beside a broad.

Not until hundreds of them lie discarded in an alley do the planes seem to remember what it is George wanted them to do. Did they suddenly decide to play ball, or feel sorry for letting George down, or did they develop a hive mind? The planes are obviously sentient, as well as muscular, since they can overpower George and carry him along despite his struggles.

Since millions of viewers (as well as the Academy Awards voters) have obviously been charmed, it appears that none of these inconsistencies greatly matter. Paperman is a magical, romantic fantasy that upholds the First Rule of Animation: Technical proficiency, however beautiful, is worthless without a strong story. Paperman has one, and audiences fell for it as George did for Meg at that train station. The appeal of this short film is, in the end, as vivid as scarlet lipstick on a clean sheet of paper.

Paperman, therefore, is more complicated than it looks, because it draws appreciation not only as a film, but as a cultural and industry artifact as well. To call it merely a new method by which two forms of animation can produce a viable hybrid is to sell it short. Paperman, to sum up, is a marriage between 2D and 3D, between technology and capital, between audience and technology, and between audience and story. It represents the next generation of advances in the art of animation, with the bonus of adoration from film and animation fans. Not even Toy Story can make such a claim; it used only one form of technology.

It remains, of course, to discover whether entire features can be produced using Meander (or its inevitable refinements). History and economics suggests that the cost of producing such films will eventually come down, and an animated feature that is a major hit could recoup the costs. As 2D and 3D teams continue to collaborate on such features, the learning curve could decrease to the point where a manageable production schedule might be feasible. One thing is certain; now that the program exists, it is not going to disappear.

--

Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman is a longtime student and fan of animation. He lives in Anderson, Indiana.