In Part 1 of this two-part series, Ellen Besen examines the motivations and effects of animation's obsession with realism.

Where did the desire to make people believe that animation was real begin? Winsor McCay has talking with Gertie long before photo-realism was even a thought.

Have you ever had one of those moments where you're doing something important, like trying to time the microwave popcorn so precisely that every kernel is popped and none is burnt, when suddenly you find yourself asking, "Why am I actually doing this?"

Did the grunts who spent whole lifetimes building the great cathedrals of Europe have moments like that? Do scientists who devote years to the mating habits of fruit flies?

It's funny how we can be so in the middle of something that it never occurs to us to question it. Like animation's obsession with realism: when was the last time we asked ourselves why are we so keen on achieving this? Is it worth the effort or have we been duped into devoting ourselves to someone else's dream or perhaps, madness?

Now you may be thinking that it's a little late in the game to start questioning this. But I would say that this is the perfect time to take stock, not towards bailing on the enterprise, of course, but to make sure that we've got a handle on our motivations. And it wouldn't hurt to be sure we really understand the implications of where this trend is leading animation, before the whole thing really takes off. Because the one thing we can be quite certain of is that when it does take off, it's going to be big.

And there is no person who makes that clearer than Chris Landreth. His work has always been interesting but his new film, Ryan, does something quite remarkable: it simultaneously reflects on the past and the future of realism in animation.

It manages this feat by sitting on the key cusp that every new medium must come to, that swing moment when it gives up the thankless role of being a new tool doing an old job and starts to work on its own terms. But before we can understand why Ryan is in this key position, we have to understand what came first.

Ryan reminds us of both the past and present marches toward realism. Courtesy of Copper Heart Ent. and the National Film Board of Canada.

The history of realism in animation is older than you might think. As early as 1832, there were rumblings about the quality of the art in magic lantern shows not being sufficiently believable and there was a wish for more realism. Yet almost 70 years later, in 1899, pioneer animator James Blackton and his partner Albert Smith were able to convince audiences that their film, The Battle of Santiago, was an authentic record of the recent event even though it was animated with cutouts of ships, with cigar smoke for special effects.

This reminds us, right off the top, that realism has always been a relative thing that changes with audience perception and experience. Like those 360 degree movie theatres which were such technological breakthroughs in the 1960s. Remember how they were built with rows of bars because the audience, who watched the wraparound presentation standing up, was prone to falling over whenever the camera tilted? Try going into one of those theaters today, if you can still find one and see what a thrill they aren't. Even kids who've never seen one before have grown past the illusion.

And imagine the reaction from today's audience to "newsreel footage" created with cutouts and cigar smoke. So this has never been just about objective realism, but about perceived realism leading to believability. Keep that in mind as we continue this exploration.

Then, of course, there was Winsor McCay, whose fluid technique, developed in the early part of the 20th century, was decades ahead of its time. But McCay was strictly interested in personal expression. It seems to me that it was the commercially driven obsession with realism that turned animators into the Dr. Frankensteins of the modern art world. And that, of course, leads us to Walt Disney.

Interestingly, Disney's early cartoons were praised for embodying the principles of modern art. But by the early '30s, Disney had taken his studio in a direction that was the antithesis of the modern movement: while the rest of the art world was busy breaking away from the boundaries of realism, he began a steady, highly organized march towards it.

Walt Disney (right), pictured here with Salvador Dali, often teetered between modern art and realism with his films. © Disney Enterprises Inc. All rights reserved.

There was nothing inherent in drawn animation that demanded realism, so why did Disney do this? Some reasons were certainly practical: he wanted to take animation into commercial features and couldn't do it unless his characters could generate believable emotion. The decision to study real movement as a foundation for performance was brilliant. But it didn't require changing the aesthetic of the whole studio over to realism. In spite of his few later flirtations with modern art, it's more likely that Disney subscribed to the old fashioned idea that realism equals fine art and the change of direction came from a wish to have animation taken more seriously.

But still, Disney never had to face the full dilemma of animated reality because the possibilities in 2D were self-limiting. No matter how realistic the design and movement becomes, 2D is still clearly art and not live-action. Therefore, the world it occupies is immediately recognizable as something totally other than our own and with that, a built in license to change the rules, however dramatically, is granted.

The Disney style wasn't so much realistic as "realistique." It was grounded in real movement and real structure but even the most realistic elements were, in fact, highly stylized, although this wasn't obvious to the eye of the average viewer.

This was actually a key factor in the studio's success. Instead of putting real and fantasy elements at the extreme ends of their continuum, both were kept, each on their respective sides, hovering around the middle. Different enough to be clearly distinguished from each other, each side still had enough in common with the other that the audience could accept that they belonged in the same world. In balance, believability was achieved.

You can see this right away if you compare the character designs in Snow White to the approach used in the Fleischers' Gulliver, a feature from the same era. Unlike Snow White's coherent approach, Gulliver has three totally separate styles of both design and movement: the highly realistic Gulliver, achieved with rotoscoping, the semi realistic romantic leads and the distinctly rubberhose supporting characters. None of these groups of characters fits with the others, an unintended effect that greatly weakens the film.

Snow White pushed the boundaries of realism mixing realistically rendered human characters with more cartoonish characters.

One way or the other, Disney's success with the realistique approach came at a price. When he moved to realism, he also adopted, almost wholesale, the film language and performance standards of live-action film. Yes, he could now make animated feature films with human characters who could hold an audience's attention for 90 minutes, but only by putting a straightjacket on this most versatile medium an unnecessary limitation which stymied innovative thinking.

Disney's decision had a profound effect on animation taking it simultaneously forwards and backwards. It's not overstating the case to say that we have been struggling within the dilemma he created ever since.

But what would Disney have done with a true third dimension? There were, of course, other animators who were beginning to explore that issue even while Disney animators were perfecting classical animation. Model animation created new possibilities but also added new complications, especially in the hands of such talent as Willis O'Brien and Ray Harryhausen. The technological leap that put animated models such as King Kong into the same world as live-action actors opened the door on a new type of storytelling that tapped deep into our psyches. Now there could be films that were like waking dreams and nightmares, like mythology come to life, starring fantastical creatures and people just like us.

In these films, something impossibly real was being inserted into our world, creating an altered reality rather than a totally new one. So the more realistic the design and movement of the animation, the better. The real elements such as the actors had such absolute, automatic audience identification built into them that they naturally set the standards for credibility. It was the animator's job to match that, not fight it.

Harryhausen had a deep sense of the importance of this. Pioneering as he went along, he not only advanced the standards for building and animating creatures, but also accounted for atmospheric details like the draft that would be created by the wing action of a giant bird. So when the live-action plates were being shot, he would have fans available to stir up waves and dust. The result was a much greater sense of integration between the fantasy elements and the real ones, which set a new standard for what audiences would accept.

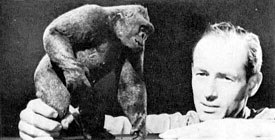

Harryhausen with his creations like Mighty Joe Young blurred the line between fantasy and reality.

For a long time, classical and model animation existed side by side, each dealing quite separately with realism within the boundaries of their particular technology. In fact, though Harryhausen identified himself as an animator (and, of course, was the true, if uncredited, director of most of his films) he did not identify with the cartoon community. Frustrated that, for the general public, the word "animation" had become a synonym for cartoons, he even gave his process a new name, Dynamation, to clearly distinguish it. And for classical animators, model animation was barely a blip on the radar.

Then along came CG and suddenly, worlds collided. Model animators and classical animators each brought different advantages to the development of the new technology. But whose approach would dominate? Would classical animators simply add the extra dimension to their existing technique and carry the field? Or would the model animators exert their obvious superiority with 3D and finally get a little respect? And most importantly, how did this effect the development of realism?

In spite of appearances, the dust hasn't settled on this subject yet. In the next article we'll explore these questions, which have everything to do with the future of realism in animation, of animation itself and by extension, of cinema in general. This is more of a cliffhanger than you may think.

Ellen Besen studied animation at Sheridan in the early 1970s. Since then she has directed award-winning films both independently and for the NFB, worked as a film programmer and journalist, taught storytelling and animation filmmaking at Sheridan and given story workshops at many institutions and festivals, including the Ottawa International Animation Festival. She is the director of The Zachary Schwartz Institute for Animation Filmmaking, an online school that specializes in storytelling and writing for animation.