How did kids survive prior to the introduction of educators into children's programming? Martin Dr. Toon Goodman takes a look at the impact of their presence.

Who's educating our children? Parents or the TV?

But increasingly...parents are looking to TV to help them do a better job of raising kids...Inside those (TV) networks, a growing number of Ph.Ds are injecting the latest in child-development theory into new programs. Newsweek, November 11, 2002

How to say this firmly: raising kids is an impossibility that usually works out anyway. Tom Tiede, Self Help Nation

This months column, dear readers, is brought to you by a scarred and grizzled survivor. My parents, ever mindful of their monumental ignorance of what Moms and Dads do after the umbilical cord is sliced, attempted the daunting task of raising me anyway. Somehow, despite the mistakes, child development magically happened. The entire process was accomplished with nary an educational cartoon to help them along or a single script supervised by a doctoral-level professional. Yet all was not well; I was fated to suffer severe educational deprivation. I was forced to rely on the public school system for my formative learning, bereft of even the merest shred of animated tutelage. Its true; I was never a beneficiary of modern psychologys blessings. No Blues Clues. No Dora the Explorer. No Rolie Polie Olie. When I entered the school system Sesame Street was still eight years from its debut on PBS. It should be considered a miracle worthy of Lourdes that I am able to write this column at all, save for one thing: as I look around at those who grew up with me, it was much the same story for all of them. And the kids are all right.

Still going strong, Sesame Street started the educational trend in children's programming 33 years ago. Courtesy of Sesame Workshop.

Enter the Ph.Ds

Dont ask me how. Back then, coyotes went flailing off cliffsides, felines had nutcrackers applied to their tails by mice, and Dishonest John might halt walloping Cecil in order to ask the audience: "Do you think theres too much violence on TV? Those are just a few examples, of course. We also had Popeye pummeling, Mighty Mouse mauling, and the Fantastic Fours fracas-fraught festivities. Bugs Bunny could certainly be dynamite, and little was learned about cooperation in the adventures of Sylvester and Tweety, or Foghorn Leghorn and a certain barnyard dog. I cant even begin to recount the lessons that Goofy taught us regarding safe behavior. The only counting lesson to be learned was when one character presented another a cup of tea and asked, One lump or two? before the mallet did the math. This however, is the 2000s, and the new mood is best summed up in the November 11, 2002, Newsweek article, Why TV Is Good For Kids. In this article we learn that an army of Ph.Ds are now heavy contributors to the scripts for animated shows. The cartoons are scrutinized, analyzed, test-marketed at daycare centers, and are guaranteed to be educational lessons in cooperation, self-esteem and overall healthy development as estimated by, well, an army of Ph.Ds.

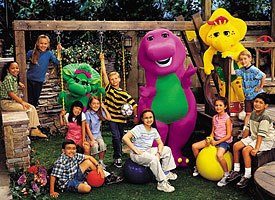

Psychologists routinely analyze children's shows such as Barney & Friends and come up with data on what is being taught. Photo by Dennis Full. © 2002 Lyons Partnership, L.P. All rights reserved.

The article, by Daniel McGinn, details a happy afternoon at the Yale psychology department wherein we find five undergrads dissecting an episode of Barney and announcing: Ive got 9 vocabulary, 6 numbers...11 sharing, and then turning the numbers over to a data analyst who compares them with past shows. Animated fare is subjected to much the same elaborate analysis. Details are provided on how a team led by Dr. Christine Ricci from the University of Massachusetts break down an episode of Dora the Explorer by observing audience behavior minute by minute, charting it on bar graphs and analyzing the results. We also visit with Dr. Daniel Anderson (also from UMass) as he winces through an episode of Dora the Explorer. It seems that the heroine and her friend Boots paddle a canoe in the direction of a waterfall, modeling unsafe behavior. If Id read the script Id have completely blocked this, states Dr. Anderson. Later in the episode he agonizes as Dora paddles her canoe under some fallen tree limbs: Oh, God, another dangerous thing...The education is a little thinner than I would wish and its a little dubious sending them on such a dumb journey.

Oh, rather. It is reassuring to know that these intrepid researchers are on the job. Wait a minute, you say, arent you one of them too, Dr. Toon? Yes, and a UMass graduate at that (1987). Still, the state of childrens programming today makes me wonder what sort of role schools, parents and families have during these oh-so-enlightened days. Are these institutions now so archaic and incompetent that psychologists must now pick up the slack and review everything that passes under our childrens eyes? Cant cartoons simply be entertaining trivialities that let the action rip for seven to eleven silly minutes and teach nothing but what a good laugh feels like? Not any more.

Blue's Clues took educational television to a new level by introducing an interactive component. Children were asked to actively participate in the lessons being taught. Credit: Nickelodeon.

Why?

No single factor alone accounts for the tendency to make childrens cartoons the vehicles for learning and self-exploration that they are today. The best starting point in this examination might be the Childrens Television Act, passed by Congress in 1990. This piece of legislature mandated childrens shows to display an educational component in every episode. Many programmers balked, and there are hilarious stories of how TV stations passed off The Flintstones as genuine teaching about prehistoric life, or The Jetsons as a scientific program. As surely as men actually quarried rock astride dinosaurs, the Federal Communications Commission sternly laid down the law on such shenanigans and the educational edict was enforced in full. From that point on, childrens shows stepped up the hiring of psychologists and other like-minded consultants to make sure that learning happened.

The psychological community brought with it another agenda, one that met with considerable approval from both broadcasters and parents. During the late 1980s there was a trend in school psychology that paralleled the prevailing educational beliefs: self-esteem became the watchword of the schools, along with a preponderant focus on feelings. School counselors, armed with tools such as Mr. Aardvarks Game of Self-Esteem or The Feelings Journey made sure that if kids learned nothing else, they could identify anger, shame and being OK! This trend occasionally produced dubious results; American children scored lower in many academic areas than their European or Asian counterparts, but when asked to rate themselves, put their performances at the top of the heap. Nevertheless, the trend seeped into childrens broadcasting and messages stressing cooperation, tolerance, self-esteem and the healthy expression of emotions were soon augmenting educative material on TV.

Would TV stations have tried to sell this rare meeting between the Flintstones and the Jetsons as a lesson in time travel? Courtesy of Cartoon Network.

Early educational efforts (notably Sesame Street) appropriated the codes of commercial television including its advertising, and educational shows dovetailed perfectly with the new proscriptions against violence since the characters were too busy cooperating and respecting one anothers diversity to conk each other on the noggin. The third and final component of modern childrens television was added in 1992 when a large purple dinosaur brought the dimensions of caring, sharing, accepting and self-esteem to children via a personal relationship that had every child believing they had a close friend. Barney brought the trilogy of education, nonviolence and feelings to its present conclusion; though many irritated adults plotted dire fates for the simpering saurian, Barney and friends were works of genius, the templates for everything to follow. Barney also showed that through ratings and licensing and merchandising, childrens programming could make dinosaur-sized profits.

Who were parents to disagree? Televisions fill every household, and children spend more time in front of them in the course of a week than they do in front of chalkboards. Soon, psychologists and educators were defining childrens television and stringently evaluating its contents. This is accepted as being for the best, and on some terms it may be. If children are learning new material, concepts, self-love, and love for others, so much the better, right? If educators are getting a louder voice in society, whats the problem? What about the psychologists, frustrated in their efforts to obtain prescribing privileges, battered by HMOs and watching private practices shrivel as insurance companies cut their number of reimbursable codes? If they are finding cool jobs in a hot new field, why begrudge them?

Can animated children's fare just entertain instead of acting as a teacher all the time? Psychologists study Dora the Explorer in minute detail to learn what the show is teaching children. Credit: Nickelodeon.

ButWait A Minute

I certainly dont. Yet, a faint miasma hangs over the whole enterprise that I have difficulty in dispelling. Exactly why parents need so much help in teaching these same lessons has never been clear, but since the 1950s there seems to have been an increasing tendency for parents to defer to the experts: physicians, professional educators and my colleagues in the psychological community. As economic and social conditions across America changed and the two-career household became the norm for increasingly busy parents this was an easy path for many parents to follow. Yet, no one can definitively say that this has resulted in smarter or more cooperative children that sit at the top of the class while showering both themselves and others with the fruits of love and self-esteem.

Standardized test scores have declined since Sesame Street first appeared. Horrifying social anomalies, such as children killing children and school shootings, which the Road Runner generation never experienced, have materialized. Colleges have been forced to allocate considerable resources to remedial classes, and news stories about how some ungodly percentage of college students cant identify our allies in WWII, the dates of the Civil War, or find Japan on a map are common. A study conducted in my own city of Anderson, Indiana in 2000 indicated that of 200 black males entering Anderson schools as freshmen, 156 never graduated. Perhaps psychologists, educational experts and their TV shows didnt cause such things, but neither have they seemed, over the long haul, to prevent them.

To wit: child-development theories are just that theories. No matter how much revision or what sort of modernizing spin can be placed on Piaget, Kohlberg and their ilk, predicting the development of any given child is close to impossible; there being too many intervening variables in the mix, factors that muddle the nature-nurture controversy beyond hope of resolution. These theories, as general guidelines, are not useless but they are not all-inclusive either. The greatest paradox surrounding them is that they seem to assume that the child is raised in a supportive environment which encourages the unfolding of a natural developmental process; in other words, we come back to parents and family. Childrens television certainly cannot be discounted as an educational medium, but it can never be a vital tool in doing a better job of raising kids.

Past generations missed out on the multitude of children's educational shows that are now ubiquitous. Rolie Polie Olie © Nelvana.

One of the saddest emails I have received since I began writing commentary on animation came to me in January of 1999. A perturbed mother of two girls, both under the age of three, responded to a column I had done on the old Animation Nerds Paradise Website. She complained that her toddlers were being grievously shortchanged by childrens television, and that viable female role models were not adequately represented. Angry that her girls had no role model but Baby Bop, and that childrens television was slanted toward males, she stated: Tell me it has no effect on the 3-year old girl. This is clearly a case of asking childrens television to do too damn much of an important job. May I suggest shutting off the TV, telling your little moppets stories about female heroes (no, you dont need a psychologist to make them up for you), and doing the job of being a strong role model for them in your own right? Give a child attention, a nurturing environment, respect for its innate curiosity and eagerness to explore, and perhaps just perhaps a child could survive something like a half-hour of classic, uncut Looney Tunes. You may even hear them laughing.

Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman is a longtime student and fan of animation. He lives in Anderson, Indiana.