How often does mainstream Hollywood scare up an animated horror film? Alain Bielik reports how Sony Pictures Imageworks combined performance capture and keyframe animation to create a unique hybrid style in Monster House.

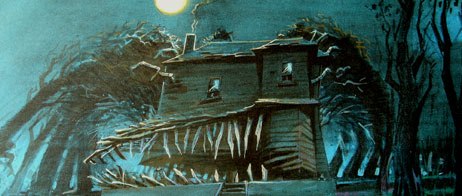

Eighteen months after pioneering a groundbreaking motion-capture technology with The Polar Express, Sony Pictures Imageworks is back at the forefront of the animation scene with an innovative computer-generated feature film. In Monster House (released by Sony Pictures on July 21), the star is a decrepit house that seems to be alive. An animated horror movie? That will be quite a departure from the traditional talking animals and other light comedies that we have come to expect from Hollywoods dream factory.

From the beginning, director Gil Kenan opted for a very stylized look. Although it would employ the same ImageMotion technology as The Polar Express, Monster House didnt use it to try to recreate reality in the computer. Visual effects supervisor Jay Redd confirms, Our characters in Monster House are indeed human, but we always approached them as stylized almost as if they were puppets. If you look at their proportions, you will notice that the heads, eyes, hands, and feet are larger than they should be. Also, we didnt concern ourselves with moisture, eyelashes or even real hair. We started our character modeling by creating actual clay sculptures of each character. Once a sculpture was approved, it was laser-scanned in, and final clean-up and patching, costumes, etc. were created. The most interesting aspect here is that we avoided symmetry at all costs. So many people model one side of a character and then simply mirror and flip to get the other side, which is highly unnatural. Admittedly, modeling and rigging non-symmetrical characters is a lot more work for the crew, but the results are so much more interesting and subliminal.

The all-important House was designed like a real house, with sketches and blueprints. The modeling and rigging team created a fantastic rig, says co-animation supervisor T. Dan Hofstedt. It had to have that flexibility to appear normal in its at-rest default pose, but it also had to be able to expand and rip and shred into this horrific beast. Actually, there were about 20 different rigs within the House rig, with a total of around 40,000 animatable controls for everything that moved on the house.

Adds Redd, We had to build an incredibly robust character because the story demanded it. We mapped out where every board would break, how they would break, etc. Character rigging supervisor JJ Blumenkranz and his crew had to get all the right pieces moving in the just the right way. The texturing part of the house is also incredibly complex. Audiences may not notice right away, but the house breaks down over the course of the film. There are many, many layers of paint on the house, and this all had to be created in textures and shaders. It is one of the most complex characters I have ever been involved in creating!

Testing Motion Capture vs. Keyframe

In order to decide what the best approach to animation was, the crew did three versions of a test shot for each of the main human characters. The first version was mocap facial data only. The second version was keyframed accents added to the mocap, and the third was keyframed only with no mocap, using the video reference of the performance as a guide. We found that the best results were obtained with the second method, Hofstedt recounts. So, we usually employed the mocap facial data as the basis for the animation, and then added selective accents and exaggerations that maintained the spirit and integrity of the actors performance. Sometimes, the mocap was left alone or only altered slightly, and sometimes for various reasons, the faces were totally keyframed. But by far, the majority of the shots blended both influences.

The scenes were shot on a 20x20-foot capture space that included a 16-foot tall vertical space to accommodate scenes with stairs, ladders, ropes, etc. The capture volume was covered by 200 infrared cameras. This volume was designed by CG supervisor Albert Hastings and capture supervisor Demian Gordon. For each performer, there would be 60-80 markers for the body, and between 40-70 markers for the face. Each set of facial markers were specifically placed on each performer, so that his/her particular range of motion and muscle structure was captured with best fidelity. By using 200 capture cameras, the crew was able to shoot with six performers at a time, capturing both face and body data simultaneously. The flexibility of the system allowed the actors to perform entire scenes without having to stop and do pick-ups.

For the human characters, my estimate is that 75-90% of the body movement ended up being mocap, with 50-70% for the facial performances. The ratio was determined on a shot-by-shot basis. The eyes and the fingers were always keyframed, and since they are the most expressive parts of an animated performance, there was always a lot of input from the animators on each shot. Personally, I think there is always room to explore the what ifs of a shot, as long as it fits the intent of the story and the personality of the character. At times, the intensity and sincerity provided by the actors did not translate 100% accurately onto the animation rig, mostly due to the fact that it was not an attempt to replicate the actors features. So the animation team often went in on top of the facial mocap data to make the desired emotion read more strongly on screen. There were also some shots where, for various reasons, we needed to add something that wasnt captured on the live-action set. Whenever we were called upon to do keyframe animation, we strove to maintain a stylistic consistency in the way the characters moved. The motion capture process has a certain texture to the movement that is slightly different than most keyframed animation.

Building an Animation Pipeline

Imageworks opted to build the facial animation controls on a two-tiered system. The first tier was based on a system that codes actors facial expressions into a library of poses based on the actions of certain muscle groups. The second tier was a proprietary keyframe tool called, Character Facial System, CFS. We developed a way to blend these two tiers into a very flexible interface, Hofstedt explains. It was theorized that the raw motion capture data on the actors faces could trigger isolated facial muscle groups in combinations to convey expressions of emotion on the animated characters. The actors made faces into the camera for many different poses (i.e., Inner Brow Raiser, Cheek Puffer, Nasolabial Furrow, Lip Tightener, etc), plus an additional set of phoneme poses. There was not a generic batch of shapes forced upon each character. Each individual actor made their version of the poses and the animation team interpreted what they did and applied it to the physics of the animation rig. The individuality of this process helped make each character unique. This interpretive process is especially what made our process on Monster House different from Polar Express. Our characters did not have to exactly match the likeness of any well-recognized performer.

The chosen frame for each of the facial expression shapes performed by the actors on video was given to the animation team who used the CFS system to create the individual facial poses. These poses were saved and named under a custom naming convention devised by the facial integration team. After a full set of facial expression shapes and phoneme poses were created and stored, they were given back to the integration team to run the facial mocap data curves. In the early stages of testing the process, there was a lot of back and forth between the facial expression shapes team and the animation team. Sometimes, wed have to adjust the range of the actual shape we had created (i.e., making the Lip Stretcher pose narrower or wider as needed), or maybe the facial expression shapes team determined that they had to adjust the percentage of influence of any given shape (i.e., amp up the influence of the Brow Lowerer). These choices were built into the facial expression shapes poses that would be driven by the mocap data. Once we settled on the facial expression shapes pose library, and determined that we needed the flexibility to go even further, we could concentrate on ways to push the performances to a new level.

Since Monster House was basically an animated horror film, it was important to maintain the intensity of the scary moments in the characters expressions and body language. One common theme throughout most of the film, which was especially true of the scarier sequences, was the application of what the crew came to call the trapezoid mouth.

While the mocap facial data was actually pretty faithful to the literal position and shape of the mouth in general, an extremely distressed mouth expression usually had to be enhanced manually into a trapezoid shape, Hofstedt notes. There was a breakthrough shot early in the production where Chowder is yelling for help. The first version was OK, but Chowders mouth looked rather mild and rounded. The actors mouth on the take was convincing for a human, but for a stylized animated character, it was missing the intensity. So animation supervisor Troy Saliba did a sketch that had the mouth corners pulled down, the lower lip fairly flat straight across, and the upper lip with a couple of distinct corners, hence the trapezoid mouth was born. This technique became a shorthand approach throughout the film to add an extra level of intensity to shots where there was fear or distress onscreen, which basically was about 85% of the movie.

The House itself was 100% keyframed (as was the dog). With this character, the animators had to strike a delicate balance in the way the House moved. It needed to feel heavy and massive, yet it also had to be maneuverable and energetic. Although animators had the ability to add squash and stretch to the animation, they strove to keep it subtle in order to maintain the rigidity of the materials.

One epic shot near the end of the movie has DJ swinging around at the end of a cable dangling from a crane swinging around a construction site. Animating the camera move alone on that shot took several artists a few days There was a very complicated choreography of managing the constraints between the camera, the character and the environment, Hofstedt recalls. Sometimes the camera had to follow DJ, sometimes it had to follow the dynamite, sometimes it had to aim at the House, and sometimes the camera drove the action. There was a careful blending between each constraint switch as to appear seamless onscreen, all the while managing the switches in speed and direction. And none of the animation could be finished until the camera got locked down

Film Noir Influence

When time came to address lighting issues, Redds background in photography and cinematography became a strong asset for the production. Monster House is a dream film for a lighter, its a scary adventure and, therefore, demands strict visual storytelling. For this movie, the shadows were just as, if not more important, than the light. In creating mystery, one has to be very conscious of not revealing too much too soon. Creating dramatic lighting requires heavy contrast, hot hots, dark darks but also the choice of color plays an important role. Some colors appear to have more luminance than others, and you have to balance that by light angles and shadow softness. I tried to take a photographic approach as the starting point, and then added the necessary drama to create interest and tension in a scary scene. I took my crew down to a stage and lit a physical miniature set with different style lights, gels, smoke effects, etc., to get everyone on the same page stylistically. Again, in creating our unique universe, we always kept the miniature set feel in our minds this comes through as shallow depth-of-field, blown-out highlights, and subtle falloffs with shadow edges.

We developed new rendering technology with Marcos Fajardo at Imageworks. The first day Gil Kenan and I met, back in Feb. 2004, we both talked about how much we loved stop-motion films, and how we wanted to make a movie that looked like it was shot on film, but using all the modern miraculous technology. So for me, light quality was an absolute key ingredient. The simplest thing to create reality in a CG image bounce light. Indirect colored diffusion. Its what makes a plastic dollhouse still look real. We mostly stayed away from ambient occlusion, because it doesnt incorporate color into its calculations. We chose our characters skin to look more like high-density foam or clay. We didnt want to introduce any materials that tried to feel like human skin or hair. Digital effects supervisor Seth Maury and I spent many weeks mapping out and testing sun color, shadow color, shadow length, etc. as this was all important to the passage of time in the film.

Other software packages used on Monster House included Maya for modeling and animation, Maxon BodyPaint and PhotoShop for texturing, and Houdini for many of the effects and natural phenomena. The crew also developed a sprite renderer called Splat, that allowed them to create seemingly rich and deep volumetric effects efficiently. These smoke and dust effects appear throughout the movie. The shots were composited with proprietary software Bonsai.

Pioneering a Hybrid Style

With Monster House, Sony Pictures Imageworks has confirmed how versatile its ImageMotion system is. It was produced 18 only months after The Polar Express using the same technology, yet the results couldnt have been more dissimilar. As the process evolves and those who are aiming for the alleged holy grail of replicating reality with the technology get closer to that goal, I think there are still many other ways to use the technology for stylized animation and storytelling, Hofstedt concludes. I think the use of mocap will evolve and expand. It doesnt have to be limited to only attempting to emulate photographic reality. It has a lot of potential to be used in new and different ways.

Adds Redd, Monster House is a very stylized film. Our main characters are humans, but our universe is particular. After all, its called Monster House! We combined performance capture and keyframe animation throughout the film to create a unique hybrid style. The technical challenges were really driven by style. We wanted to make a movie that looked different, felt different, something that no one had seen before. This was all driven by the story as well its not often that we get to make an animated horror film!

Alain Bielik is the founder and editor of renowned effects magazine S.F.X, published in France since 1991. He also contributes to various French publications and occasionally to Cinéfex. Last year, he organized a major special effects exhibition at the Musée International de la Miniature in Lyon, France.