Bill Desowitz chats with the directors of Disney's 50th animated feature and first CG fairy tale.

Check out the Tangled trailers, clips and featurettes at AWNtv!

Tangled is a first-time Disney hybrid when it comes to storytelling and technique. Images courtesy of Disney.

As Nathan Greno relates in Jeff Kurtti's invaluable The Art of Tangled (Chronicle), he was surprisingly approached in 2006 to direct Tangled (formerly Rapunzel) after Glen Keane suffered a heart attack. There he was with John Lasseter, Ed Catmull and Andrew Millstein (general manager of Disney Animation Studios). Of course, he said yes. After his work on Meet the Robinsons and his promotion to head of story for Bolt, he seemed a natural. Then, when asked to recommend a directing partner, he suggested Byron Howard, given their successful collaborations on Bolt and the short Super Rhino. When Catmull asked why Howard, Greno explained that between them they would have all the bases covered. Now we have them together for an exclusive interview about Tangled, opening Nov. 24.

Bill Desowitz: Given, Glen Keane's intention to make this a new kind of hybrid, do you think you've achieved that?

Nathan Greno & Byron Howard: Yes, yes!

NG: This movie has been very exciting for us because it does feel in many ways that it has a classic Disney look.

BH: And at the same time, it's a very contemporary, unexpected film in our pacing, our action and humor. I like this idea of branching things together. Working with Glen, having a 2D and 3D hand-in-hand approach, that was very exciting for us because it hadn't been done before.

NG: We wanted to do something non-traditional yet not cynical with a smart script and characters that you could relate to. People at the studio didn't get that at first. We love these stories and are very enamored of the classic films and tried to get the best of what those have to offer while giving the audience a film that belongs in a theater of today. We tried to push the animators to a new level and without Glen there, the human acting wouldn't be where it needed to be for this film.

BD: Talk about Flynn in this equation.

NG: Having Flynn as a thief seemed like a fresh spin, especially in contrast to Rapunzel, who is a really smart girl but is just locked away in this tower. So she has a very limited world view and Flynn could complement that as this worldly guy.

BH: He's such a crazy character -- very funny -- and with all of these characters, including Maximus, the horse, we kept looking to go off-road on a wild ride over here. And with Flynn, we kept going after characters we like.

BH: We kept referencing live-action characters we like such as Ferris Bueller and Indiana Jones, who are skilled but have a human side to them. And what we liked about Flynn is his immediate sense of charm and he thinks he's the smartest guy in the room.

BD: But he's emotionally repressed.

BH: Exactly. She's so out there and really has to dig at him to get these secrets out there.

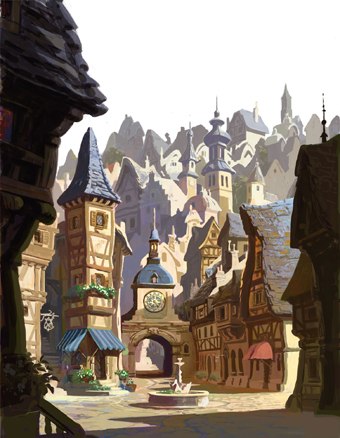

BD: The design of the kingdom is patterned after Fantasyland, and I couldn't help thinking that this part of the movie was like being at Disneyland.

NH: A part of what's going on is that it's about a girl whose wishes are coming true and she has these dreams to go out and see the world. And so when she got to the kingdom, it had to be the greatest experience ever, right? Because we love the parks so much, we talked about them quite a bit, actually, when we were making the movie. "It should be crowded in a Disneyland kind of way. Not uncomfortable but there's a lot going on to see." And we would reference Disneyland often.

BH: And we did a lot of research. We went to central Europe; we went to Budapest; Hungary; Austria, where those actual buildings came from. But at the same time, we were under the same challenges the Imagineers were under in the '50s and '60s when they put that land together: taking these 2D drawings and converting them to 3D buildings. And we had to build every brick of this town and every part of this island kingdom virtually by hand in the computer. And so it was a good reference point. What makes this charming? How does this make us feel good?

BD: And it's all about Rapunzel's artistic expression.

BH: Right, we even tried to tie her colors to the kingdom's colors and design elements in buildings -- these swoopy hair shapes that she herself does in the tower.

BD: It's all coded like The Da Vinci Code.

NG: Yeah, when she's going home, we wanted it to feel like this is where she belongs. The same thing with the way we designed Rapunzel's parents as opposed to Mother Gothel. When they're standing together, it is very clear that this is not a mother and daughter, just by the frames of their bodies, their hair, the pigments of their skin.

BD: But they all have large eyes.

BH: It's true: we debated that a lot early on because with CG you can't always get away with what you can in hand-drawn. But the more expressive and the emotional you need characters to be, it's something that you have to push. And there's one scene near the campfire where she's laughing at Flynn and she's got these huge, beautiful eyes, and you just lose yourself…

NG: You fall in love with her…

BH: You fall in love with her and he falls in love with her right there too. It's amazing because so much of the acting, especially with CG, they can do these tiny eye shifts and readjustments with the eyes where they're focusing on what you're feel that it's almost impossible in 2D, where it might seem like a mistake -- like a line jumping around -- but with CG there's micro-animation that you can do that really sells it.

BD: What were some of the personal experiences that found their way into the performances?

BH: We always ask the animators to animate from the inside out, like that king and queen moment before the lanterns are released. We talked to the animator and asked about the first time he ever saw his father cry. What did that do to you? What does that feel like? Or have you ever been in the hospital with someone who is at the end of their life? Is there something that you can bring to this that is so real and so true on a human level that it will reach everybody in the audience? And what's so great about that scene is the choices the animator made are so subtle and in context it means so much and it makes the end of the movie pay off so much more.

NG: After a while, some of these animation sessions were turning into therapy sessions. You walk out of there and you're so exhausted talking about your experiences, but the way Byron and I approached this movie is that it's a world we created and these are characters that popped out of our heads, but in order to make the movie work, the world has to be believable and those characters need to be relatable, and so we took our own experiences and the crew's experience and we put that into the movie to better engage the audience.

BD: In terms of 3-D, I really think the lantern sequence justifies it. What was the importance?

BH: When one of our story artists pitched that idea of doing this lantern ceremony, we thought it would be perfect for CG, so it was always in our heads. So to see it finally done after all the layers and layers and layers of work that had to make that happen. To be able to reach out and almost grab the lanterns is incredible to us.

NG: Yeah, and the thing is, with 3-D, we've all seen movies where we've gone out wondering why we paid the extra money to see something that doesn't serve a purpose. And so early on we knew this was going to be a 3-D film, and Byron and I wanted our 3-D to have a purpose. It gets you involved in the story.

BD: One of the best analogies was by Megamind director Tom McGrath, who said it makes you a better voyeur.

BH: That's true -- it really gets you into the movie more. And you can't find a better example for why this movie is in 3-D than that lantern sequence. It's this moment she's had in her head for 18 years; she's finally there and surrounded by this and she's got all these new emotions and her world has completely opened up and you're right there with her and see all of it right in front of you.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN & VFXWorld.