In the seventh Open Season production diary, Sony Pictures Animation chronicles how it pushed the boundaries of 3D character animation performance.

From the AWN/VFXWorld Exclusive Open Season Diaries.

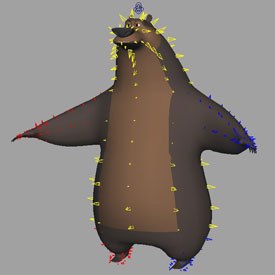

Imageworks animators were given the ability to refine poses and sculpt the silhouettes with special shapers, which were built into the surface of a character. All images © Sony Pictures Ent.

Directors Jill Culton, Roger Allers and Anthony Stacchi knew they would have to push the boundaries of animation in order to get desired performances they envisioned for Boog, Elliot and the entire cast of creatures that inhabit the town and forest of Timberline.

Fortunately for them, the Open Season animation team rose to challenges, lead by animation supervisors Renato Dos Anjos, Chris Hurtt, Sean Mullen and Todd Wilderman.

The animation needed to match the graphic style of Eyvind Earles world and the preferences of the directors who wanted snappy, cartoony, squash-and-stretch, old-style animation. So, animators needed tools that would help them maintain the characters graphic silhouette and create a 2D style of animation in a 3D world.

A fundamental, driving aspect of the look of traditional 2D films is the appeal of the drawings created by animators through various artistic cheats. In 3D, an animators ability to incorporate these cheats into his or her scenes has largely been restrained by rigs that adhere to more realistic, physical limitations.

One element of this is that 3D animators usually pose characters simply by rotating joints, but that doesnt allow for traditionally clear silhouettes. For example, an arm may be rotated up to a straight horizontal position. However, due to the physical reaction of how the surfaces of the model is driven by the joint being rotated, this may cause a lump or other similar break in the line extending from the base of the neck out to the wrist.

If this movie were being hand drawn, the animator would simply draw a clean line, unrestrained by any physical limitations. This gives the characters a designed, caricatured feel rather than a solid, realistic feel. So, Imageworks animators were given the ability to refine poses and sculpt the silhouettes with special shapers. The shapers were built into the surface of a character. An arm, for example, might have eight sections or slices, each of which an animator could move and scale independently using control points. An animator could move an entire slice, creating an effect like a rubber hose, or grab individual points and pull the surface of the arm on one side. Using these shapers, the animators could maintain straights and curves, in which the inside of an arm would curve and the outside would have straight lines that bend sharply at the elbow of the character.

Imageworks artists solved the problem of shaping the silhouettes of characters that had thick fur through the use of fur volumes being added to the rigs.

Imageworks artists also had the challenge of shaping the silhouettes of characters that had thick fur, which had potential to significantly compromise the shapes we were trying to achieve. This was solved through the use of fur volumes being added to the rigs. The shapes would be sculpted based on pulling the skin volume of a character around, but the results would also be reflected in the fur volume. While this did not show exactly what the final fur would do, it provided enough of an idea that the artists could get basically what was necessary out of our poses.

The rigs were also built with the capability of squashing-and-stretching almost any part of the body. There are many ways to use squash-and-stretch in traditional animation, but on Open Season, the crew opted to use squash-and-stretch as something that is felt more than seen. In past 3D films, this effect was primarily achieved by posing joints in a way that would give the impression of squash and stretch, but frequently limited the extent to which it could be used, or resulted in awkward, unappealing poses that we could only hope to hide within the overall movement of the character. On Open Season, squash-and-stretch was achieved with an amazing range of pliability. Using these squash-and-stretch capabilities in conjunction with shaper controls allowed artists to squash or stretch the characters while maintaining volume. A character pointing quickly, for example, might have its arm stretch unnaturally long and thin as the arm snaps out, and then settle back into its default length and volume in one or two frames to then hold in the pointing pose, just as would have been done on a traditionally animated film.

While the issue of sculpting a characters silhouette had been dealt with by building shapers into the surface of the models, we did still face one more significant challenge as a direct result of this methodology. Once a scene left animation, it went to final layout for any last camera adjustments that were necessary. But since the shaper work we were doing was so camera specific, any significant camera change could potentially have an adverse affect on the characters silhouette. To deal with this, we showed early animation passes to layout for the express purpose of getting feedback on what they would need to do with the cameras once the scene reached their department. At times, this would result in the final layout camera changes happening while the scene was still in progress in animation. Other times, it meant setting up a camera that we could modify in animation which layout would then use as a guide for their final camera work. But however the individual scenes ended up being dealt with, this turned out to be a blessing in disguise since it forced even more inter-departmental communication than we had managed to have on previous shows.

The rigs were built with the capability of squashing-and-stretching almost any part of the body. There are many ways to use squash-and-stretch in traditional animation, but here its meant to be felt more than seen.

Another way to achieve a more traditional feel was through the specific approach we took to animating, which could be best described as a combination of pose to pose and straight ahead animation.

Pose to pose animation is built on the idea of key poses, also sometimes referred to as storytelling poses. Theyre the few poses your character(s) needs to hit within a scene in order to convey the core emotional goals of the performance, as well as illustrating the most extreme points of the characters movements. As with every approach to animating, this has advantages and disadvantages.

The advantages are that it tends to read more clearly than any other approach can. This is because youve worked out the extremes of the shot before hand, and simply need to work from one pose to the next as you break the scene down. Also, you are assured that things will happen in the right time and place, because youve worked it all out in the beginning stages of the scene. This approach also makes it easy to be sure your actions will all take place within the framing of the scene, and will lend themselves to the overall composition of the shot.

The disadvantages tend to be that the animation can end up having less of a natural feel due to the fact that all the movements were pre-planned. The opportunities for spontaneity are very limited, so it can end up looking a bit stilted. Also, this more analytical approach sometimes causes a scene to loose some fluidity because rather than following an evolving progression of movements, youre trying to hit specific targets along the way.

Straight ahead animation is a more instinctive approach in which you move ahead from start to finish on a scene, working out movements and acting as you come across it. This approach is best suited to fast or very broad actions for a number of reasons. One, it lends itself to getting a nice flow to your actions since youre focusing more specifically on movement than on story-telling poses. Youre also more likely to create spontaneous and creative animation that would have otherwise been very difficult to plan out.

Pose to pose animation is built on the idea of key poses a character needs to hit within a scene in order to convey the core emotional goals of the performance. They also illustrate the most extreme points of the characters movements.

Unfortunately, the disadvantages of straight-ahead animation far outweigh the benefits in a production environment. You can easily lose track of your timing, and end up running out of room to convey what the scene requires because youve gotten too wrapped up in evolving movements vs. sticking to the core point of the scene. Its also a much more difficult approach to use in terms of showing your early pass of a scene to the directors since its not going to be clear whats happening in the scene until its almost completed. Also, its much harder to hit your crucial storytelling poses when your focus is so significantly on movement. And, of course, its harder to keep your animation within the confines of the scenes framing and to work with the composition of the shot when you havent set any limitations on the overall actions of the character.

Working with a combination approach offers the best of both worlds: you can hit the main story-telling poses very clearly, but still maintain the flow and spontaneity of straight ahead animation as your scene moves ahead.

The Open Season crew did this by starting with key poses set to stepped curves. This typically entails posing virtually every element of the character on your main emotional points of the story, setting a key on all and then moving on to the next pose. When an animator would render a scene using this approach, each pose would be held frozen in place until the next key is reached, so the character pops from one pose to the next. This ends up looking very much like the pencil tests that we would have filmed in traditional animation. When creating these poses, the focus would be specifically on conveying a clear emotion, as well as a strong silhouette, so it would be easy to know the scene was heading in our intended direction, as well as to show our initial idea to the directors for review. As the scene progressed and the primary elements were approved and working well, straight ahead passes on certain elements of the characters, like ears, tails or sections of broad animation, could be employed.

This meant, for some CG animators, learning an entirely new approach to animating compared to what they were used to. In some cases, they picked it up very well, but other animators who did not use the pose to pose/straight ahead combination approach would have to find alternative ways to get their initial thoughts in front of the directors before investing too much time in their scenes. One common way was through filming reference footage of themselves acting out a scene, and cutting it into the sequence to show in dailies. Another was through thumbnail drawings. Both of these processes are very familiar to directors and supervisors from traditional backgrounds, so it allowed us to have some easily communicated alternative approaches to the style we were attempting to achieve.

The variety of characters in Open Season meant having to approach each with a notably different stylistic frame of mind.

The variety of characters in Open Season also meant having to approach each with a notably different stylistic frame of mind. Boog is a huge, 900- pound grizzly bear with a smooth, relaxed attitude. Elliot is a small, wiry mule deer with a high-energy personality and frequently changing moods. Beth is a petite, quirky park ranger who laughs at her own jokes when no one else does. Shaw is a lumbering, viscous, wise-cracking conspiracy freak. Gordy is a fatherly, old man with an egg-shaped body and stick legs. These physical and personality traits all required a broad approach to how each moved without making them feel like they came from totally different films. For reference, the animators initially looked at films that tackled similar challenges, such as Disneys 101 Dalmatians and Sleeping Beauty.

Eventually, however, the characters took on a life of their own, and as a result, the animation began taking on its own unique feel, achieving the desired goal envisioned by the directors.

Various artists at Sony Pictures Animation, who worked on Open Season, have contributed to the writing of this series of production diaries on the making of the film.