Bill Desowitz reports back from a recent trip to Laika in Portland.

Many copies of wigs of Norman's hair had to be made for stunt sequences. All images courtesy of LAIKA, Inc.

What a difference since I last visited Laika four years ago for the Oscar-nominated Coraline. Everything about the stop-motion craft has improved with the ParaNorman zombie fest (opening Aug. 17). The Rapid Protype Printing (RPP) overseen by Brian McLean now has color, allowing faster face replacement with greater articulation; the puppet fabrication under the supervision of the masterful Georgina Hayns is much more tactile (wait till you get a load of Norman's hair); the costume design by the intrepid Deborah Cook stitches together every conceivable fabric you could imagine; the rigging from Oliver Jones is more naturalistic, as is the lighting from Tristan Oliver; and the sets supervised by the resourceful production designer Nelson Lowry evoke a timeless New England that's bucolic yet foreboding.

As director Chris Butler suggests, ParaNorman is "John Carpenter meets John Hughes." But after nurturing his first feature for 12 years, Butler thinks "John Hughes is the best reference here because he always used comedy but there was a strong emotional current underneath. And that's the biggest part of this: you care about Norman."

Norman (voiced by Kodi Smit-McPhee) is a social misfit bullied in school that communicates with the dead and is the only person to combat the zombies, witches and ghosts that haunt his town.

"They're a great combination of flavors because, if you're making this as a family film, the comedy really tempers that horror stuff," adds co-director Sam Fell, who was thrilled to return to his stop-motion roots.

This seems like the perfect follow-up to Coraline, only ParaNorman is more skewed naturalism than quirky theatricality. No wonder Laika president/CEO Travis Knight still gets his hands dirty as lead animator. How could he resist playing with zombie puppets?

"This particular story really spoke to me and I think it has great resonance with the crew here," Knight explains beside a beautiful meadow set. "I think the story of ParaNorman in large part is about the people who are making it. It's this story of outsiders -- people who are marginalized for what they are and what they represent. But, also, at the same time, these people have extraordinary gifts, and that's true of Norman and this crew here. Because of that core, I absolutely had to be involved. We all found each other in the land of misfit toys."

Knight says it's all about the convergence of technology and art, and the directors concede that ParaNorman could not have been made as effectively without the latest advances. Take the RPP: thanks to the speed and adaptability of both upper and lower faces, they can be churned out and held in place by magnets to create a wider variety of expressions. The faces are painted in Photoshop, modeled and animated in Maya; then baked in resin in the printer. There is no need for painting afterward and the added verisimilitude of teenage acne, witches' warts and zombies with squash-and-stretch would not have been possible without the new 3D color printer. Even a Scooby-Doo-like van is assisted by rapid prototyping for a wild action set piece.

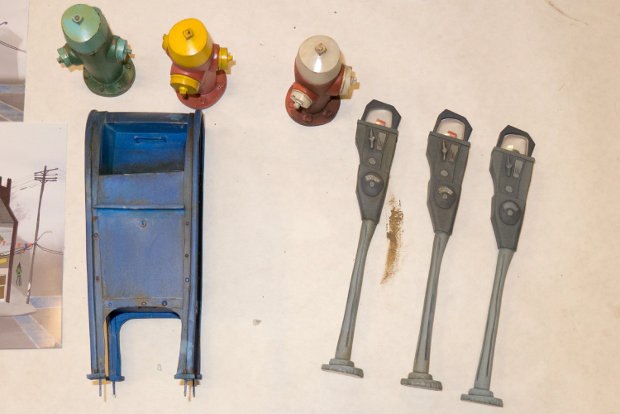

As for the sets, we visited the school (where a play within a play reveals a deep, dark mysterious past), the main street based on one in Salem and the messy home of Norman's uncle, the deceased Mr. Pendegrast (John Goodman). For Lowry, it was a trip down memory lane, since he utilized his hometown of Weymouth, Massachusetts, for inspiration. He emphasized that the sets contain no straight lines: everything is askew in keeping with the naturalistic vibe. Also, the woodwork, dirt and blades of grass play to the strength of stop-motion's tactile quality.

But even though Laika makes use of CG enhancement, they refrained from using it too much. "At one point we talked about doing elements of [the environment] in CG," Knight adds, and I said, 'No, no, no -- we're going to do that practically.' And then when I was out there stabbing my fingers with bug pins and wires and scraping my hands, bloodied with wires, I thought why the hell did I agree to this? But in the end, because it was all done practically in camera, it definitely has a certain feeling that we couldn't have captured in CG. It has a sort of veracity to it.

"If you look at some of the materials here, for instance, this big tree and all the shrubs back there are made out of corrugated cardboard. The cover on the trees is made out of shredded paper and chicken wire. If you look at the grass here, it's made of Astroturf material and bits of glass. So when the light hits it on camera, it picks up these little glistening things, which gives it a beautiful quality. And then to give depth, we add a few thick scrims."

Lighting is vital to the aesthetic of ParaNorman. Oliver says nothing is too wacky unless it needs to be. "All our environments are very natural," he explains. "Normally you put the puppets in the environment and you light the environment around the puppets. But here we've lit the environment first. If the contrast is strong, then the contrast is strong; if the shadows are dark, then they're dark." Interestingly, they looked at Conrad Hall's work on American Beauty and Road to Perdition, as well as Atonement, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and even Pulp Fiction. They paid close attention to light coming through a window or door.

Obviously this not a typical stop-motion movie: just the latest from the land of misfit toys.

--

Bill Desowitz is former senior editor of AWN and VFXWorld. He's the owner of the Immersed in Movies blog (www.billdesowitz.com), a regular contributor to Thompson on Hollywood at Indiewire and author of James Bond Unmasked (www.jamesbondunmasked.com), which chronicles the 50-year evolution of 007 on screen and features interviews with all six actors.