Bill Desowitz gets a first look at Pixar's new short, Presto, with director Doug Sweetland: a "cartoony cartoon" with lots of traditional magic.

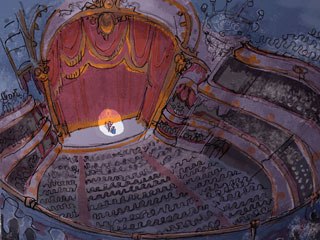

Presto, the newest Pixar short, which premieres at Annecy on June 10 before screening theatrically with WALL•E on June 27, is a real cartoony departure. It's a slapstick ode to Warner Bros. and Tom and Jerry toons, in which a turn-of-the-century magician finds himself in a hilarious onstage feud with his hungry rabbit. Talk about a carrot and stick reversal. Presto, the magician, has never experienced such humiliation, as the crafty rabbit, Alec, gives him a taste of his own supernatural hocus pocus. There are plenty of magic hats and vaudevillian antics during the frantic five minutes, punctuated by iconic squash-and-stretch gyrations and bug-eyed reactions. Presto gets egg on his face, is attacked by a ladder, has his clothes torn off, gets electrocuted, uncontrollably dances a jig and is hurled high into the rafters. And the stuffy audience cheers every moment of it.

For first-time director Doug Sweetland, the animator who's worked on every Pixar feature up to Ratatouille, as well as the Boundin' short, Presto was a revelatory experience -- just as shorts should be.

replace_caption_presto02_DougSweetland.jpg

"What I ended up pitching and what ended up on screen are two different things," he says. "The only consistent thing is that it's a magician and a rabbit. The idea of it being a throwback to old cartoons came along the way. I pitched the magician as a sympathetic character who gets dumped by his rabbit. And at an opportune moment, a fan boy rabbit comes knocking at the door asking for an autograph and he incorporates this knock-kneed newcomer into his act almost immediately. And all these hat gags sprung from that. I wanted both of these characters to be innocent... Once it got approved, that's when my troubles started and the real work began, when Presto becomes a really antagonistic character, who's more oblivious than mean-spirited up front."

Sweetland got deeply lost trying to find a working story. "There were months and months when I was pitching and bombing." But the Pixar brain trust of John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Pete Docter, Bob Peterson and Lee Unkrich proved invaluable.

"It's like when you sign up for the Army: you don't expect them to go easy on you. And it was very much a boot camp-like experience. But it was the opportunity of a lifetime to be taught by these guys. I would be a fool not to trust them, but I did everything to hold onto my ideas. And, ironically, the first time I went in to pitch something where I had no idea whether it would work or not, was the first time that they bought it. It ended up being a total laugh fest.

"My main misconception in the beginning was that story was about the best collection of ideas relating to a topic. But it's not: it's all about sequence. Andrew Stanton at one point sensed that I was holding onto old ideas. 'Well, just try it out, draw it -- it takes five minutes.' It was that 'stop holding on, stop holding on.' That was the advice that got me to go into places and see where it went, rather than trying to control the process.

"The other thing is that the hats are a device in the story. And for the longest time, I was fixated on the gags. The story just didn't work from a character standpoint and Bob Peterson said, 'I know this is going to sound weird, but the short should work without the hats at all.' His comment got me to focus purely on the two characters and charting a progression of their argument."

The Tom and Jerry influence stemmed from a genuine story need and was helpful in establishing a quick setup. In order to get to the conflict quickly, viewers had to know what the rabbit needed.

Thus, the Warner Bros. and Tom and Jerry influences stemmed from a genuine story need. "We needed a really quick setup, we needed to know what the rabbit needed right away, and we needed to know what the conflict was. And that was where we spent the majority of time, working out the first 30 seconds of the short. When it became clear that Presto was a comic villain, then it couldn't help but point back to these great antagonistic relationships between Bugs and Elmer or Yosemite Sam. And so that became a model for us. Serendipitously, we had Teddy Newton as our character designer, who is steeped in classic cartoon history and styles. He designed our characters for us and John [Lasseter] was very clear up front about having them be iconic: signifiers of the magician and the rabbit you would expect him to have.

When it became clear that Presto was a comic villain, the filmmakers used the great antagonistic relationships between Bugs and Elmer or Yosemite Sam as a model for the main characters in the short.

"As far as animation style, that was tricky to find too. We did look a lot at Tex Avery, but mainly our source material was Tom and Jerry, because it's very clear that Presto is Tom and Alec is Jerry. And we looked at Warner Bros., of course, especially any performance-oriented cartoon, particularly the one where Bugs is fighting with the opera singer, called Long-Haired Hare [directed by Chuck Jones in 1949]. And there's a lushness to Tom and Jerry that's almost in Disney territory. Warner Bros. is a pretty good middle ground for fullness and crack timing. Tex is more joke-oriented and since this is basically like a stand-up piece -- we are telling visual pantomime jokes in animation -- we looked at Tex just to see how he controls motion to deliver jokes."

Sweetland thinks Presto was a refreshing change of pace from the more nuanced, emotionally complex and hyperreal Pixar features. Fortunately, a lot of the technology for the squash-and-stretch in 3D came with Brad Bird and The Incredibles. "The challenge was artistic," Sweetland suggests, "and the hardest thing was to de-program everything I had learned on the features...

"With the short, the main thing is, 'Where's the punch line?' And let's design movement for the punch line, because you don't want to water down the screen with a bunch of ancillary movement and nuance. It takes a high degree of control to stage things. It's one of those counterintuitive challenges where you think animating less will be easier, but doing anything with less means you have to think a little bit more."

Also integral is the look of Presto, supplied by Production Designer Harley Jessup (Ratatouille), which Sweetland admits is a cross between those two terrific turn-of-the-century magician movies, The Prestige and The Illusionist. "This is perfect because the classic cartoons sprung out of a vaudeville style. You have true magic with the hats and it's nice to think of it as overlapping with the modern age, but it's not overwhelmed by technology. Harley was great at making that world seem lush and decadent and alive. And that was important for the comedy. You had to have this environment of total formality.

"We kept looking at the London Opera House and the Paris Opera House and classic vaudeville theaters here in San Francisco, including the Geary, which we actually took a tour through. Presto has to try so hard to be a high-status person and impress the crowd, which is the aristocracy. Overstatement is a motif of the short, and Harley is the perfect person for that. The theater is one of my favorite things about the short."

To get an environment of high formality, the filmmakers looked at the London Opera House, the Paris Opera House and classic vaudeville theaters like the Geary in San Francisco for set design ideas.

However, populating this ornate theater with 2,500 patrons (even with the help of Massive software under the supervision of Matt Webb) was an expensive proposition. There was talk early on of just doing some cutaways to reveal a few audience members. But Sweetland thinks that seeing just the back of their heads makes it seem all the more real, and adds to Presto's humiliation.

"I couldn't be happier about getting a [full] crowd into that theater. We got the chance to create a world inside this theater, which is like a steroid-pumped vaudeville theater that can only exist in fantasy with such a ridiculous scale. But it has every bit of Pixar realism to lend the grandeur of it."

Jessup definitely dressed their world from the Ratatouille prop room, as they rummaged left and right and had sticky fingers.

"One bit of technical R&D: We were pushing the characters pretty fast and there were lots of scrambles and we noticed that the motion blur after animation was a little fuzzy and faint, so we had the time to go in and try different composites. We tried to get the characters a little more solidified.

"There's a tendency with standard motion blur to, say, have a character's foot during a scramble de-materialize just a bit. It looks a little too diffuse. We didn't do a uniform change in motion blur, just those instances where the animation is really pushing the characters to the limit: about a dozen shots or so. We were going for a combined dry brush or distortion drawing look, trying to emulate hand-drawn animation. I was glad that most of the animators really dug working on a cartoony cartoon. They found the slapstick pretty liberating."

Bill Desowitz is editor of VFXWorld.