The famed Japanese illustrator divulges how his first movie design experience on Coraline has impacted his style.

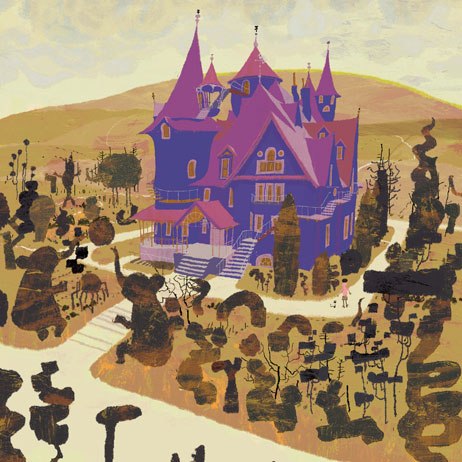

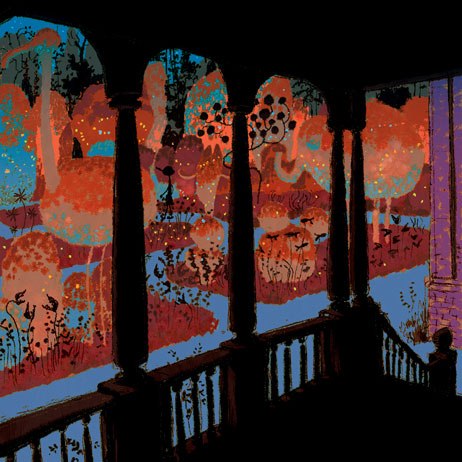

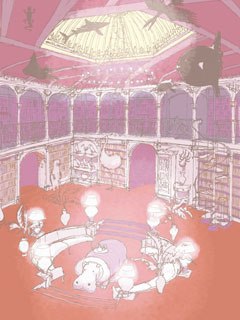

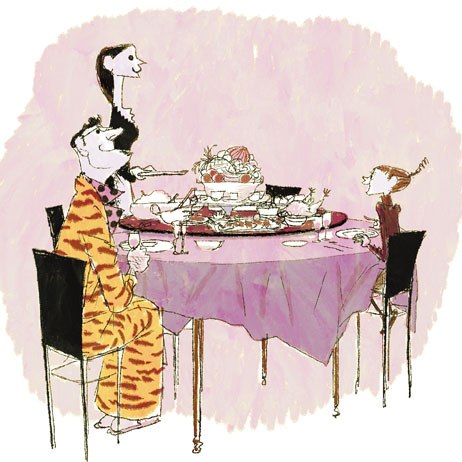

In what turned out to be a crafty coup for Coraline (opening Feb. 6 from Focus Features), director Henry Selick tapped renowned Japanese illustrator Tadahiro Uesugi to serve as visual designer for the stop-motion adaptation of Neil Gaiman's novella. In Coraline, the eponymous young protagonist unlocks a mysterious door in her new home to a fantastical parallel world that's much more exciting than her drab one.

"Tadahiro's heavily influenced by late ['50s] and early ['60s] American illustration, the kind that's portrayed in Mad Men, back when photography wasn't the first place you'd go to solve things," Selick told Metropolis. "It's a fresh, illustrative style, very graphic, but he adds a touch of soul -- a tiny bit of reflection in a water surface, a shadow, a disturbance of atmosphere. His work breathes."

Uesugi recently discussed his first-time cinematic experience doing concept designs on Coraline with AWN, and you can enjoy some of his exquisite work.

Bill Desowitz: How were you first approached by Henry Selick to be the visual designer of Coraline? Your beautiful, minimalist, '50s/'60s retro look seems to have been a perfect match.

Tadahiro Uesugi: When I met Ronnie Del Carmen and Enrico Casarosa of Pixar, in Tokyo, they asked me if I was interested in working on movie projects in the United States; my answer was yes. They delivered my interest to Mike Cachuela, a former colleague of Ronnie and Enrico at Pixar, who recommended me to Henry Selick.

At the beginning, it was supposed to be a small project over a few weeks to simply create characters; however, I ended up working on the project for over a year, eventually designing sets and backgrounds, on top of drawing the basic images for the story to be built upon.

BD: What were your impressions of the Neil Gaiman book and its illustrations and what inspiration did they provide? Have you met Neil and discussed your concept work?

TU: I haven't had a chance to meet Neil Gaiman himself, but I drew the designing process upon the story of the Coraline book released in Japan. (By the way, illustrations of the Japanese version of Coraline book are done by a Japanese illustrator.)

BD: What did Selick convey to you conceptually about what he was looking for in terms of design, color and light?

TU: I was told which images in the book I was going to translate into the movie; except for that, everything was basically up to me. Henry's only instruction was: "Design with your own ideas; but we would like to see something we've never seen before!"

BD: Would you be more specific about what you visually translated?

TU: First, I was asked to design characters for the movie based on my reading of the Japanese book, NOT based on the illustrations of the book. Then I started designing the setups and the backgrounds; however, I was given directions and resources for these designs. Soon after, I received the script and started designing according to the descriptions in the script; therefore, if I tell you what I translated from the book, I would say the basic design of the characters.

BD: I take it this was your first experience working on a movie?

TU: I've done some advertisement projects for movies before, but this is my first time to work on the movie itself.

BD: What was the process like for you?

TU: I joined this project where there were no visual images available; so that I started drawing the characters based on my reading of the book. After the basic images were set up, I kept drawing characters and backgrounds, and designing sets based upon them, which were to be the basic common idea for the staffs to build the movie.

Art of the Other World Living Room.

BD: Were you inspired by other animated works? When I look at your work, I immediately think of 101 Dalmatians.

TU: I was influenced by graphic designs from the 1950s to 1960s for my design. Therefore, 101 Dalmatians is one of my favorite animations, being a movie which represents the style of that era.

BD: Tell us about your contributions and what you've gleaned artistically from the Coraline experience. What are you proudest of?

TU: Most of the projects I've done are covers of the books, advertisements in magazines and posters; however, I've always thought that I have a point of view of moviemaking whenever I've worked on those designs. At the same time, I thought I will never have a chance in commercial movie production projects because of the style of my illustration, which I never thought is suitable for movies, especially in Japan. Therefore, I have sort of taken out my frustrations on such projects as magazines or posters, for not being able to work on anything about movies, which I've been yearning for.

On the other hand, Coraline was a very exciting project because I was able to directly exercise my ability to the full extent. I had a hard time going back to my senses after I completed Coraline, as if I [had] the diver's disease. However, because I was able to let out almost all of my frustrations on this project, it actually helped me become interested in more planar graphic designs. With less perspective and therefore less three-dimensional appearance, I believe my illustrations will articulate more colors and composition of the shapes.

BD: Did you get the chance to visit the set at Laika in Oregon?

TU: I visited Laika twice. Though they just began building the sets, some were already closer to completion.

BD: What did you think?

TU: Those sets surprised me with the magnitude, which is impossible in Japanese stop-motion animation. Also, what amazed me was the professional sense of the set designers, who were trying their best to re-create jagged lines on the edge of the sets, which is a typical style when I'm drawing the outlines on my illustrations.

Other Mother and Other Father welcoming Coraline to the Other World with a deliciously-prepared meal.

BD: And did you see footage?

TU: I saw the preview on my computer. I believe it is going to be a great movie, and am really looking forward to seeing the complete version.

BD: In your book of illustrations, Three Trees Make a Forest (also featuring the works of Del Carmen and Casarosa), you wrote that you must capture your ideas quickly now that you've discovered Photoshop. What's it like working digitally and what kind of Sketchpad do you use?

TU: I am using Intuos3 PTZ930. Because it has been a while since my designing process became digital in full scale, drawing by hand with paints became such a cumbersome work. I believe the merit of digital processing is a great reduction in time in materializing the images from the inspirations in my head. On the other hand, it takes a great patience in doing the same with hand-painting. It would be wonderful if I could produce the design by hand-painting which has the same quality as the digital production.

BD: Speaking of animation, what are your some of your favorites?

TU: Sleeping Beauty, animations by Tex Avery, the modern style by UPA Studios, film title designs by Saul Bass and works of Yuriy Norshteyn of Russia.

BD: And what have you seen recently that you like?

TU: Among what I saw recently, Peter and the Wolf, winner of the 2008 Academy Award for the Best Short Film [Animated] was very good.

BD: Coraline marks the first stop-motion feature in 3-D. What do you think of stereoscopic 3-D overall as a storytelling tool?

TU: I don't have a good impression from the 3-D works I've seen in the past. However, I've never seen the works done by the latest technology, so I am looking forward to seeing the new ones.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of VFXWorld and AWN.