Doug TenNapel and Mike Dietz take us on a full tour of The Neverhood, a cutting-edge studio which uses claymation to create interactive games.

Download an exclusive, sneak preview Quicktime movie of an animated sequence from Skullmonkeys, The Neverhood's soon to be released game. 479k © The Neverhood

Also, download a fun Quicktime movie of the creative team at The Neverhood. 165k © The Neverhood.

An anonymous warehouse in an Orange County industrial park is home to one of the most creative people in the video game industry. Just beyond a tidy receptionist area is a large room which contains a melange of artistic tools, from computers to animation disks, clay, acrylic paint and even live animals. Slappy, a hamster, which appears in the latest video game from the inhabitants of this dorm-room like studio, happily prowls his cage for food. A black scorpion which failed to make an appearance in Skullmonkeys occupies another cage, much to Slappy's relief.

A clay set in The Neverhood studio. © The Neverhood.

This is the conference room of The Neverhood, a game development company founded by Doug TenNapel, who assembled a group of his friends and formed a company where innovation is the name of the game. Informality is the rule here, and titles are unimportant as evidenced by the Neverhood's business cards. As "mayor," Doug has the vision to make the Neverhood work.

Orange love beads from the `70s which resemble throat lozenges strung together festoon Doug's office door. A Persian rug seems subdued under a wood-stained desk and neon-colored walls striped with orange and green paint. Doug's 6'8" body is sprawled on a print sofa as he contemplates a technical problem with a Neverhood inhabitant, Mark Lorenzen, who has been a friend for 14 years. We'll return later to interview Doug, but first Mike Dietz, "Ditch Digger" and lead animator, will show us the rest of the studio and explain how a group of 13 friends came together to create Skullmonkeys out of clay, latex and ingenuity.

Studio Tour Time

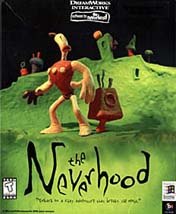

Skullmonkeys is the second puppet animated game for The Neverhood. Their first title, The Neverhood, introduced Klaymen, the character, to the video game industry and most of the team to puppet animation. The Neverhood was a puzzle adventure game developed for the PC and released in December 1996. The Neverhood team put in many 100-hour weeks to deliver the game on time and under budget to DreamWorks Interactive. They were in uncharted territory, having no experience in developing for PCs, working in puppet animation, or in doing a puzzle game, or even in working together. It's true that many of them had worked at Shiny Entertainment, on Earthworm Jim, which was created by Doug, but Jim was a platform game, done in traditional 2-D cel animation. The Neverhood was something altogether new, different and exciting. Only Doug had worked in clay before. Mike admits he was terrified, but that "the stop-motion animation community was completely open with sharing information, which is 180 degrees different from the video game industry where everything is a matter of national security."

Mike shows us how they built Klaymen's body with latex around a brass armature. He demonstrates how to do surgery using an exacto blade, slicing into Klaymen's body to reposition the armature. A box of eyes and mouths backed by thumbtacks lend Klaymen an array of emotions. Like playing with a Mr. Potato Head, Mike exchanges a mouth and eyes on Klaymen and suddenly, he looks surprised.

Neverhood visionary, Doug TenNapel. Photo © The Neverhood.

Mike explains the controlled design process used in their games. "Most of the interactive game animation was done on paper first to help make all the hook-ups easier to pull off. With Doug's movies [mini-sequences in between levels] we mostly only storyboarded first, with only the more difficult scenes animated out on paper. I used a Panasonic digital AV mixer to flip between video of my drawings and my puppet." The puppets were shot on huge sets lit from overhead against a green screen. Large sets were required because the camera could not be restricted. The most frustrating aspect of working with the puppets was that they had physical limitations, unlike hand-drawn animation where anything was possible. Many puppets were broken in an extreme squash or stretch. He shows us a can of Pepsi covered with sculpey which appeared in the "boiler room" of their current game. "Whatever works," Mike says as he concludes the tour.

Note: For a more detailed look at the production processes used in animating The Neverhood's stop-motion games, read Mike Dietz's article, which includes a Quicktime movie of the animator at work.

Let the Interview Begin!

Doug's meeting with Mark Lorenzen is finally concluded, and he drives us to Coco's (a family-style chain restaurant) for lunch, in his wife's unassuming sedan. Doug wears a plaid shirt over his Skullmonkeys T-shirt and a Kermit watch. His thick glasses and beard don't hide his boyish enthusiasm. Despite his success in Hollywood, he is unpretentious and candid. He grew up in the outskirts of Turlock, California in Denair, raised around farms. His guilelessness is real, but he is not naive. His integrity is paramount.

Pamela K Thompson: What was your first job as an artist?

Doug TenNapel: I was a graphic designer at Sea World in San Diego. I was a mural artist. I designed costumes, props, and did whatever they needed me to do, menial tasks. I learned stage lighting from Debbie Rosengrandt which I use every day now in stop-motion animation.

The Neverhood's eponymous debut game was released by DreamWorks Interactive in 1996. © The Neverhood.

PKT: How did you get involved in animation?

DT: I loved cartoons when I was growing up. I started making flip books when I was seven years-old. I used text books because they are big and thick. I drew on the page edges, things like a man walking. I was not a good animator. I was always impatient. My stuff looked bad. My animations got better after working and doing it wrong and haphazardly. This lead to my ability to break the rules. What I never lost was speed. That's a non-negotiable for me.

PKT: Who were your biggest influences in animation?

DT: Mike Dietz and Harriman who did Krazy Kat is a real inspiration to me. I admire people who did their own thing just like I am doing my own thing. I was influenced by Warner Bros. cartoons because I watched so much of it, I must have been affected by it. The Disney stuff did not have as much impact for me. I can learn more from Warner Bros. I can see it better. If it was the 1940s, I'd be working for Warner Bros. I would work for Clampett if I could work for anybody.

Animator Mike Dietz demonstrates how he animates puppets in a "green screen" set which will later be replaced by backgrounds in the computer. © The Neverhood.

PKT: What are your favorite TV shows?

DT: Gilligan's Island is the greatest TV show ever made, like Laurel and Hardy with sound. What a great premise. Currently the only TV show I watch is Siskel & Ebert because I tend to be home on Sundays. And I watch The X Files. My favorite movies are the darker comedies from the Coen brothers, like Raising Arizona.

PKT: And your favorite video games?

DT: Robotron, the original version. Myst, Mario 64, Command and Conquer...

PKT: Tell me about the early days.

DT: Angie and I were married in 1990 and I was making $4,000 a year doing freelance illustration in San Diego. I worked about an hour a day and played Ms. Pac Man at the Laundromat. Our expenses were about $400 a month. I was desperate for work. Then AFT (American Film Technologies) got a project called Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, a Saturday morning cartoon show. They had to find 150 animators. I barely got hired, I'm not good on presentation. I learned how to read a storyboard and an x-sheet and got paid minimum wage. There were a lot of mediocre talented people there including myself who were all overwhelmed. I became the lead animator and worked from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Ron Brewer was the director on Killer Tomatoes and translated Warner Bros. cartoons to me, which changed my animation a lot.

I did some freelance work for Real Time and Associates. Dave Warhol gave me a 486 [computer] to work on at home. I did some freelancing on Batman for Park Place. The money I made freelancing was used to make a down payment on our house.

I was desperate for work and applied to Blue Sky Software, and was going to take a job for $22,000 US, but then a bidding war happened between Blue Sky and Park Place and I ended up starting at Blue Sky at 28K ($28,000 US). I was the lead artist on Jurassic Park [the game] for Genesis and we did some puppet animation in that. We got to use a raptor puppet from the movie that cost 75K ($75,000 US). I can still remember how the armature worked. I cold-called Steve Crow at Virgin.

Mike Dietz: David Bishop called me into his office to look at Doug's portfolio, which were these wonderful paintings of toasters done on paper bags.

DT: You can't always believe a portfolio. People get caught up in presentation. I don't know if I'd hire myself. I'm not good at presentation but my CONTENT is very strong.

MD: Once is there anyone can do the polish.

DT: Discipline is an underrated talent. And patience. We always admire in others what we lack in ourselves.

MD: Everyone at The Neverhood has one thing they are very good at and many things they are good at. Everyone has to wear a lot of hats.

DT: The team is well-balanced. Everyone is confident enough to defer to others and everyone has their strengths and weaknesses. I'm real interested in seeing the whole team do well and learn. I don't want to do the same job all the time.

PKT: What qualities do you look for in an employee?

DT: They have to be versatile, have a sense humor, be loving, friendly and be fun to be with. I'm real selective in choosing an employee. I trust all my employees to go above and beyond the call of duty. I expect more than what I can pay. I can't ask that of people I don't know. I've picked up guys at every place I've worked.

PKT: How did The Neverhood get started?

DT: After I left Virgin, I went to Shiny where we did Earthworm Jim. I decided to leave and start my own company and got a commitment from Mark and Ed Schofield. Two weeks after I left Shiny, I announced at E3 that I was starting my own company and DreamWorks offered us the best deal to do our game. By the end of the summer we had our team together and had funding. DreamWorks allowed us to survive. They wanted to break into the game industry and needed some experts to help them. It was a good combination. They took risks along with us. I admire that. They are not doing the same old thing that everyone else is doing. When you are creating zero you aren't adding anything to the world.

PKT: What do you like best about working in games?

DT: The freedom. Where else in Hollywood can you get money to write your own story, do production, do your own voices and not have to work with a union? This is a business where you're free to pioneer. The thing I love about it is that it makes you think on your feet and respond quickly. We're at the point where filmmaking was in the 1920s. Game animation still has a long way to go.

PKT: What advice do you have for other game developers?

DT: Project-oriented hiring is bad for games. It's hard to find great people. The problem with the industry is people don't deliver when they say they will. Hit your deadlines. Be respectable and responsible to your financial partners. Don't break your promises. Hold up your end. I was disappointed that we were a month late with Skullmonkeys. It doesn't matter if we were a day late or an hour late. If we didn't hold up our end of the deal then how can we expect the people we are in business [with] to hold up their end? I have expectations from them to have autonomy, support, competence and timely payment. Developers have to be responsible with the team, budgets and designs. And deliver a quality product.

Skullmonkeys, Neverhood's new game, for Sony PlayStation. © The Neverhood.

DT: Learn life drawing and a 3-D program like 3D Studio Max. Notice I didn't mention anything about doing puppet animation in your garage?

PKT: What's next for The Neverhood?

DT: We're not sure. We will do a third game for DreamWorks but we are not sure if that is going to be our next project. We may do something in another medium. We are probably going to do something with 3-D [computer animation] in our next game and that scares me. I would be less scared going to medical school than going into 3-D animation. But we have to try it. The best creative stuff happens when serious limitations are imposed.

At The Neverhood, whatever they do next, you can be sure that it will be a new challenge to the team, giving them an opportunity to do what they do best - to be inventive, ingenious and to create something unique.

For a more detailed look at the production processes used in animating The Neverhood's stop-motion games, read animator MikeDietz's article.

Pamela Kleibrink Thompson is an independent recruiter. Her past clients include Walt Disney Feature Animation, Fox Feature Animation, and Dream Quest Images and Engineering Animation Inc. and interactive companies such as Raven Software, Hollywood On Line, Activision, and Adrenalin Entertainment. Thompson is also a consultant to colleges and universities helping them design their animation training programs. As manager of art at Virgin Interactive Entertainment, she established the art department, recruiting, hiring and training 24 artists, many with no previous computer experience. Her animation production BACKGROUND includes features such as Bebe's Kids, the Fox television series The Simpsons, and the original Amazing Stories episode of Family Dog. Thompson is a founding member of Women in Animation and active in ASIFA. Her articles on animation, business and management topics have appeared in over 40 periodicals. She is currently writing a book called The Animation Job Hunter's Guide.