Karen Raugust investigates how guilds get together to deal with the changing digital technologies affecting production design, cinematography and VFX.

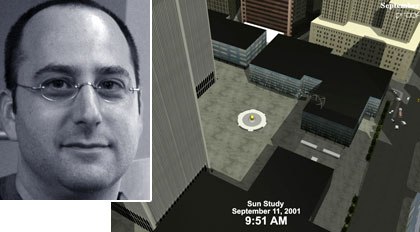

Like Proofs work on World Trade Center, previs is morphing the pre-production stage greatly. © Paramount Pictures Corp.

The technology committees of the Art Directors Guild and the American Society of Cinematographers have created a joint working committee to deal with the digital technologies that affect production designers, art directors and cinematographers, not to mention vfx supervisors and others involved in film production. The committees objectives include sharing information and creating and promoting a nonlinear workflow that allows for both efficient decision-making and consistency all along the production pipeline.

The ADGs technology committee has been focused, in part, on promoting this new nonlinear workflow paradigm, in which creative decision-making is centered in the art department. The 3D previs serves as a digital hub of information, aiding not only the production designer, but also other departments in making effective and efficient decisions during preproduction.

Alex McDowell, a production designer who heads up the ADGs technology committee, says the art department now has access to cost-effective 3D design tools such as Maya and XSI. We were able to take back some of the design work that had gone to the VFX supervisors when workstations were $10,000 to $100,000, he says. A lot of design was happening after the designer was done.

On the 2002 film Minority Report, which involved a futuristic design, McDowell and his team set up a previs using 3D modeling tools and a workflow that was digitally based, networked and digitally archived. We created, by default, a fully digital art department that worked in a completely different way, explains McDowell, who has subsequently worked on Cat in the Hat, The Terminal, Corpse Bride, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Bee Movie.

Other art directors and production designers have adopted the same techniques over the last few years. The art department is central to preproduction and is becoming the digital hub of information, adds McDowell. Its digital, free-flowing, and nonlinear. Storyboard information, camera positions, avatar actors, sets, sequences and vfx can be integrated into the same previs, allowing problems and issues to arise and be solved months before shooting. We create a virtual production space that represents the physical production space, explains McDowell, adding that the digital data can then be output and used in subsequent phases of production.

Part of the ADGs goal is to disseminate information about these tools, making it available to its 1,500 members and encouraging them to take advantage of the technology. McDowell points out that not all members are using 3D modeling tools during preproduction yet, but they could be. I use the same tools on a $15 million movie as on a $100 million movie, he emphasizes.

Meanwhile, the ASCs technology committee has been involved lately with the issues arising from the move to digital from film, affecting everything from image capture through digital interface and, ultimately, digital projection. In particular, cinematographers are concerned with color management, data management and digital standards that would allow them to maintain image integrity and consistency over the entire pipeline.

Curtis Clark, a cinematographer and chairman of the ASC technology committee, notes that digital image capture is starting to occur on films as diverse as Superman Returns and Prairie Home Companion. With digital acquisition, there is no intrinsic color space as there is with film. We need to figure out how to integrate image and look management into the workflow, Clark says. We need consistency to be maintained at least through the digital mastering stage. And there will be a point in a little more distant future where there will be more deployment of 2K or 4K digital projection. In the mean time, there are already digital distribution platforms, including DVD, HD-DVD, Blu-ray and digital TV. So the industry is working toward an end-to-end digital system, which opens up many technical issues for cinematographers.

With changing technology demands, the role of production designers like Alex McDowell (left) and cinematographer Curtis Clark are expanding and changing.

Common Issues

Since art directors and production designers are active mainly during preproduction, while cinematographers come into the picture just before the camera starts rolling, the ADG and ASC had been working independently on the technical issues that face each group respectively. But they began to realize their issues werent mutually exclusive, and thus formed the joint working committee. The cinematographers single greatest collaborator, aside from the director, is the production designer, insists Clark.

Were using tools that are very helpful to cinematographers, McDowell adds, citing previs as a key example. This could become a component of the whole production workflow pipeline. He points out that the data compiled in the digital hub of previs can flow through shooting and post-production, with editors, gaffers, vfx supervisors, cinematographers, production designers and directors accessing it for decision-making purposes, or importing it into their own systems as a starting point for their work.

The previs could help solve some of the color-management issues that are of concern to the ASC, as well. Information about how a particular red wall should look, or what lights and filters should be used, could be stored and carried all the way through, says McDowell, so when the scene gets to DI and the color timing, that nugget of information remains in place. That would enable the scene to feature the color the designer and director wanted rather than an approximation.

Previs applications and the previs work by the production designer could be more effectively integrated into the planning of scenes and shots, Clark agrees, adding, Wed like to see more consistent work being done on developing the previs side as a way of integrating the look management [the tools that allow color correction tweaks to reference materials] into the preproduction and production process.

Were really connecting the two pieces of the pipeline, McDowell asserts. Its clear that the tool sets were both creating are mutually beneficial.

We all have the same concerns and ambitions in common, confirms Thomas A. Walsh, production designer and president of the Art Directors Guild. Were all overwhelmed with the new technologies. We so fundamentally affect each other, and no one has enough experience yet to say, This is the one way to do it. Were all hunter-gatherers in the wilderness, trying to do this on our own. We need a clear perspective on what the tools are and how they are best used.

Cinematographers seldom are involved in preproduction, and therefore have to make a lot of assumptions about what the production designers, who have already completed their work, had in mind. With 3D modeling and rendering, cinematographers eventually could be involved earlier, such as at the set design stage, at which point they could decide how to light a scene and set up other elements, according to Ron Frankel, president of Proof, a previsualization company, which recently worked on World Trade Center. It would make for a more efficient design process, he says, noting, the general goal of promoting communication among departments is a positive one.

Thomas Walsh (left) and Kim Libreri believe a set of digital standards would be beneficial.

Impact on VFX

While vfx supervisors are not directly involved in the ASC/ADG joint initiative, the guilds work will have an impact on the VFX community. Vfx supervisors are increasingly coming on board earlier in the filmmaking process, and view the previs as an increasingly essential tool. The design department is giving them a space in which they can work, says McDowell. Theres much more collaboration in the design process, which makes us both happy.

He notes that once the previs, which is created three or four weeks after the start of preproduction, has incorporated information about sets, cameras and sequences into the 3D animation space, its an easy pitch to the producers that the vfx supervisor should be in on it. Its practical and efficient to make effects decisions at that point, such as where animation or matte paintings should be used or where set extensions are needed.

McDowell points out that production designers have been frustrated when their vision hasnt been carried out accurately in the VFX, while vfx supervisors have been frustrated when theyve had to fill in the blanks after the designers have scattered. All this due to a lack of collaboration between the two departments. We can design the full arc of the film in all aspects [using the previs], McDowell says. We can negotiate the line between live-action and set extensions. This coordinated planning saves time and money.

In addition, some of the data from the previs can be used for building VFX in post. Youd be carrying files through the process, reports Walsh. There would be no redundant or obsolete information. Youd maintain a continuity. Theres a lot of duplication waste, and it adds lots of time to the process. We cant go on forever making films for $300 million or $400 million.

The information created with 3D modeling tools during preproduction all is getting handed downstream, adds Frankel. VFX will inherit a lot of information that otherwise they would just be guessing.

Kim Libreri, vfx supervisor at ILM, notes that modern movies have a significant number of VFX shots, and often rely on multiple vendors, who are increasingly involved earlier in the process, while the art department and designers are still doing their job. Its hard to keep track of which vendors are doing what, he says, and of which versions of scenes are being used. You get out of synch, Libreri says. People think with digital effects you can change anything, and you can, but it costs time and money. You could spend millions working on the wrong design.

Scott Andersons Digital Sandbox was key in keeping quality control consistent on Superman Returns, which was the first major film to use the new Genesis digital camera.

Millions of lines of software define what a VFX pipeline is, Libreri continues. A set of standards is desperately needed. He points out that any shared information from other departments would assist the vfx supervisor, even if its just small steps at first. Communicating the edits and the flow of how the editor and directors are thinking would be so helpful.

Thomas Tannenberger, vfx supervisor and owner of Gradient Effects, notes that the VFX community would like to be in on the ADGs and ASCs conversation. For one thing, it has many tools it would like other filmmaking departments to embrace.

For example, Gradient Effects is promoting the use of a Lidar scanner to capture exact measurements on location, whether a one-mile section of highway or a front porch, which is then used to accurately create the previs. You can see to the last tree branch what issues, if any, need to be resolved, Tannenberger says. He notes that some people shy away from the Lidar because its difficult to make sense of the billions of data points, but Gradients proprietary software organizes and facilitates the data flow, handing over to Maya the just the information needed, all within a few hours.

Such technology is useful for production design as well. On Southland Tales, according to Tannenberger, the art department designed an airship to be placed into downtown L.A., which required exact measurements of all the buildings. It would have been a nightmare with traditional means, Tannenberger says, noting that a CG model is a lot like a model in the real world. You cant just go in and size it up. You have to add elements and re-texture it, which is time-consuming and gives all of CG a bad reputation.

Tannenberger believes that this kind of technology could be integrated into a nonlinear workflow of the sort the ADG and ASC are promoting. In the case of a Lidar-scanned highway scene in Premonition, for example, all the departments involved were tapping into this data, he says. That included the art department, the stunt people, camera people, set dressers, grips and the director. Lidar is a very valuable tool, he says. We want to get this across to every production we work on.

Clark points out that ensuring consistency in color throughout the pipeline, starting with the previs, would benefit the VFX department. Everyone, whether the vfx supervisor or the editor, would be looking at exactly the same image, no matter what kind of display was used. There is software available that stores color information as metadata that accompanies the file, Clark adds. If we could get a handle on that, starting with the previs, that would be a huge asset in the process. Accurate references, with an established color space, contrast, dynamic scale and other properties, would allow VFX supervisors to fit their 3D objects into the same color space as would be seen in the final film.

Scott Anderson, vfx supervisor and president of Digital Sandbox, which specializes in VFX and image management, says he shares the goals of creating standards for color and image management, as well as creating a workflow that allows communication throughout the process. At Digital Sandbox, we want to protect the image from beginning to end, he explains. Our approach is to maximize the power thats in the negative.

But he cautions that, although the current lack of standards is an issue in terms of preserving quality and communicating goals, creating standards shouldnt lead to a least-common-denominator result. He points out that theres a huge difference between what Ansel Adams did with a negative and print and the standards-compliant output of a one-hour photo store. Both cinematographers and vfx supervisors, he says, push the envelope of the medium, which means going above and beyond the average.

Anderson also wonders, while acknowledging that having a central place for color and other decisions will benefit everyone, whether the hub always should be located in the art department. In some cases, decision-making might better be centered in the editorial or camera department, depending on the discretion of the individual production.

Real-Life Applications

The processes being discussed by the ADG and ASC are already evolving on their own, at least to some degree. McDowell points out that the discussions the two guilds technical committees are having are all in real terms, not theoretical, and that all the things theyre looking at are already in use.

Libreri points out that supervisors on most VFX-heavy films already use some sort of central database to keep everyone closely coordinated. If youre not, millions of dollars get wasted. Its a disaster. This is particularly true if there are companies sharing assets, with each vendor having a slightly different pipeline. Its quite a complex process, he says.

Similarly, it has become fairly commonplace to do 3D planning. Frankel notes that this has evolved organically, but he points out that each production, with its unique team, uses different tools in different ways. Making everyone aware of what worked successfully on a particular production would help the industry as a whole. Bringing the weight of the guilds to bear will help bring it to a wider audience and make it more standardized, Frankel says.

Clark comments that collaboration among production designers, cinematographers and vfx supervisors is already happening, and that all have to keep abreast of innovations affecting the digital workflow. We want to develop industry-wide methods of consolidating planning and creative thinking, so everyone is on the proverbial same page.

Karen Raugust is a Minneapolis-based freelance business writer specializing in animation, publishing, licensing and art. She is the author of The Licensing Business Handbook (EPM Communications).