Alain Bielik chronicles the adventure of bringing Exorcist: The Beginning to the big screen for the second time.

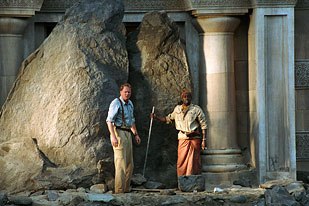

The process of bringing Exorcist: The Beginning to the big screen was a scary story. All images, unless otherwise noted, courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures © 2004 Morgan Creek. All rights reserved.

One of the scariest movies ever made, The Exorcist traumatized millions of spectators with its groundbreaking make-up effects by Dick Smith and inspired direction by William Friedkin. It grossed more than $400 million worldwide, a staggering amount in 1973. Two sequels, in 1977 and 1990, failed to generate a similar response from audiences. However, the very successful Version You've Never Seen reissue ($30 million) in '00 gave rise to the new prequel, Exorcist: The Beginning, which has generated more controversy and acrimony than anyone ever anticipated, with two different versions produced one by Paul Schrader that was scrapped for not delivering the prescribed goods and a more conventional scare fest by Renny Harlin that Warner Bros. is releasing on Aug. 20. But there is talk of releasing both versions on DVD next year.

Hired to direct the prequel was John Frankenheimer. The veteran filmmaker worked on the project for several months before poor health obliged him to step down. He eventually passed away only one month after he had resigned. Schrader was then brought in to helm the project, but when executives at Morgan Creek watched his first cut of Exorcist: The Beginning, they found that the movie was not scary enough to their taste. Schrader had delivered a subtle psychological thriller instead of the in-your-face horror flick that they had in mind.

Starting from Scratch

Since the movie did not provide the requested frights, Morgan Creek initially looked for a director to do a few re-shoots in order to enhance Schrader's version. When that did not pan out, they took the unprecedented decision of throwing away just about everything Schrader had shot and starting from scratch with a new director. The movie was entirely re-shot in Rome, Italy, with Harlin at the helm, a new script, some new actors, and visual effects supervisor Ariel Velasco-Shaw overseeing plate photography. However, when the shot list grew from 150 to more than 500 shots, Harlin felt more comfortable bringing in Brian Jennings who had supervised the effects work on all of his latest movies. A veteran of large-scale productions, Jennings wasn't available for principal photography due to a prior commitment to Man on Fire.

The new visual effects supervisor was faced with the daunting task of jumping into an enormous project for which he hadn't even shot the plates. "Basically, we had four months to do 600 shots and a very little budget to do so!" laughs Jennings. "We didn't have the money to farm out all the shots. So, the only solution was to set up our own studio. I figured I needed about 20 people. I especially looked for artists that had their own gear. We paid them a salary for their work and a rental for their equipment. For those who came without gear, we bought a bunch of Macintosh G5s. 2D work was done in Shake, Combustion and After Effects under the supervision of Jeremy Burns and Tom Mahoney, while 3D effects were created in Maya and Houdini by a team lead by Robert Emrich."

430 Shots In-house

Originally, Schrader had planned to have all the effects realized in Italy by Cinecitta's Proxima, a company owned by the son of great cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (who shot both versions of the movie). However, when Harlin took over the project, the decision was made to relocate the entire effects work in America. "The previous supervisor had already hired Meteor Studios to do a sequence involving CG hyenas. I brought Pixel Magic in to do other sequences and we did the rest with our own unit. So, the organization was completely different from what had been arranged for the Schrader version. We tried to do as much as we could in the production effects unit, but there just wasn't enough time. We still managed to produce some 430 shots in four months with a crew of 20"

This digital fly was just one of the CG creatures created for the film. © 2004 Morgan Creek. All rights reserved.

One of the issues with the Harlin version was that it had been entirely shot in Rome. As the action was supposed to take place in the Middle East, Jennings' crew had a lot of location work to do. They produced about 50 matte paintings for static scenes and 20 CG environments for tracking shots. "We didn't have to go to the Middle East to capture background plates," reveals Jennings. "We had all the plates we needed in the Schrader version, which had been partly shot in Morocco. The problem was that we were not familiar with the footage and it took a lot of time to find the right plates. In some instances, we managed to find empty shots of Moroccan scenery that we combined with the new live-action plates. In many cases, though, we had to paint out the actors and some elements before we could use the images as background plates. Fortunately, both versions had been shot in sunny conditions by the same cinematographer. The footages actually matched up pretty well."

The opening scene of the movie features the most elaborate 3D matte painting created by Jennings' crew under the supervision of Timothy Clark. The scene starts with a long shot of the Gizah pyramids in the 19th century. Then, the camera drops down to a street set and catches up with the actors. The key aspect of the shot was to track the camera move on the live-action set, a task carried out in Boujou. After that, CG artists worked out the camera move backwards, starting from the first frame of the plate, and generated a digital environment that perfectly blended with the real set.

Many of the landscapes were retouched.

Besides retouching landscapes and backgrounds, Jennings and his crew tackled many other "invisible" effects such as breath enhancement. Whenever a demon appears in a scene, the air around the characters becomes very cold, which makes their breath visible. Supervised by David Crawford, the effect was created in After Effects as a particle animation and added in 150 shots in which the camera was moving. For some rare static shots, real breath elements were photographed on a black background and composited in.

Of Fangs, Claws and Wings

Wild animals play an important role in several scenes in the movie. "There's one sequence in which a character is attacked by five hyenas," says Jennings. "Harlin had tried to get some footage with real hyenas, but they just stood there in front of the greenscreen. So, they shot the plates with the actor pretending to be attacked and relied on CGI for the hyenas. Meteor Studios created those shots, using dog footage and documentaries as a reference for the animation. During plate photography, the crew had used wires to pull the actor's costume in order to simulate the presence of the hyenas biting the character. The animation of the digital hyenas was then timed with this practical effect."

Meanwhile, Jennings' unit had its own load of animals to deal with, namely flies and crows, two species traditionally associated with the Devil. Featured in more than 100 shots, a swarm of thousands of flies was animated in Houdini as a particle animation with a layer of behavioral animation. As for the crows, dozens of hand-animated CG birds were used to complement the handful of real animals that had been photographed on the set.

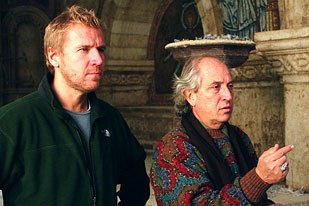

Director Renny Harlin and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro plan their next horrifying shot.

A Vision from the Past

50 shots were assigned to Pixel Magic, which had a long working relationship with Jennings. They included a sequence in which the main character, played by Stellan Skarsgard, walks in the desert in the middle of a sand storm and is suddenly transported to a battlefield from another time. Tens of thousands of dead warriors appear, crucified upside down on the hills around him. "The scene had been shot with less than 10 real people as the warriors around Skarsgard," says Ray McIntyre Jr., visual effects supervisor and vp of Pixel Magic. "The rest of the army is entirely computer-generated. We had 10 different models for the digital bodies, plus the CG cross itself, all built and rendered in LightWave. The plates had been shot in Italy, but the landscape did not work for the sandy desert that was required. Thus in every shot, Skarsgard had to be rotoscoped and unwanted set elements had to be removed in order for us to add matte-painted landscapes behind him. We also generated the sand storm itself, using hypervoxels in LightWave for background elements and real elements of blowing sand for the foreground."

The highlight of the sequence is a spectacular pullback that starts tight on Skarsgard and stops two miles away, revealing the traumatic sight of the crucified army in the process. "The pullback is 732 frames long that's more than 30 seconds of screen time," notes McIntyre. "We had two live-action plates to work from. The first one was the start of the pullback with Skarsgard photographed on a minimal set. The second plate was the very end of the pullback where the camera comes to rest, two miles away from the original location. That plate featured some real cross elements in the foreground. The in-between was totally computer-generated."

According to Mike Hardison, CG supervisor for Pixel Magic, "The first part of the job was to track the camera moves. Then, we heavily retouched the first plate, adding hundreds of CG crosses and bodies and replacing the original landscape. After that, we projected the last frame of the early pullback onto CG geometry and did the same with the first frame of the final pullback. It gave us a start position and an end position for our digital environment. Once the match-move was complete, we could seamlessly blend the two live-action plates with our digital landscape. Many layers of CG blowing sand were then added in the scenery. Each layer had hold out mattes for bodies and crosses to create the feeling of distance and depth to the blowing sand."

Enter the Gore

Pixel Magic also tackled some of the goriest aspects of the movie, the very element that prompted the studio to re-shoot the whole film. Part of these effects involved a female character that is possessed by the Devil. As a result, she has superhuman abilities that allow her, for instance, to spiderwalk on a wall. "Some of the things that she does are really extreme and CG animation was the only way to achieve them," comments George Macri, visual effects producer for Pixel Magic. "We modeled a digital double of the actress in Maya and did a Cyberscan to capture her features. The most spectacular of these shot has the character hanging upside down on a cross and then, bending up backwards, which is obviously impossible. To achieve this effect, we actually combined elements extracted from two different plates. We took the legs in one plate and the torso in the other one. For each plate, the actress was positioned in a way that allowed her to perform the move. By combining the two body elements, we created an impossible and very disturbing move. When she jumps down off the cross at the end of her move, we switched to a full CG double, except for the hair and face. Clothing simulations were done in Maya with Syflex, then the actress' actual face and hair from live-action plates was grafted onto the CG body to create the final image."

In a few months, fans will get a chance to see both versions of the films on DVD.

In what is probably the goriest scene of the whole film, a character uses a shard of glass to slice his throat open back and forth all in glorious close-up To show the shard piercing the skin, Pixel Magic added a CG replica in the empty hand of the actor, and painted a CG wound. In the second shot, the actor was wearing a two-inch green band on the neck and simulated the slicing action with a harmless shard. CG artists reconstructed the missing skin by using still photographs of the actor, and painted the injury, frame by frame. "We mainly used Commotion & After Effects to paint and track the effect," observes McIntyre. "It was a very difficult set of shots as the camera was really close to the action. This said, I'm not sure all the shots will be in the final cut. It's so graphic"

More Re-shoots

Well into post-production, it was decided that a new ending yes, a third one was required. The crew flew back to Rome for another three days of shooting. Since there was no time for a lot of set building, the team relied of visual effects to accomplish the scene. Kleiser-Walczak was brought in to execute some of the most complicated shots, with the remainder staying in-house. "We had our team running 24 hours a day for three weeks in order to pull this off," noted Randall Kleiser, visual effects supervisor.

Although Jennings is very proud of what he's accomplished with his team, the hard work and long hours took a toll on him: "Honestly, I wouldn't want to do it again! It was such an undertaking. I'm still very happy that we managed to deliver so many shots with so little money. This is an approach that I had already tested on previous projects. We did 200 shots on Driven that way and all 450 shots of Mindhunters too. Without an in-house unit, Renny would have been obliged to give up many sequences. So, it's a great satisfaction for me that he was ultimately able to get everything he needed."

Alain Bielik is the founder and special effects editor of renowned effects magazine S.F.X, published in France since 1991. He also contributes to various French publications and occasionally to Cinefex.