Troublemaker Digital and The Orphanage tell Alain Bielik how they made Grindhouse rock with creative vfx for Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino.

The Planet Terror segment of Grindhouse features a unique pistol-packing mama. Once the gunleg design was approved and built, Eyetronics scanned and built a CG model. All images courtesy of Dimension Films.

Working as a vfx artist for director Robert Rodriguez has one main advantage: every project is sure to be completely different from the previous one. After the Spy Kids movies, The Adventures of Shark Boy and Lava Girl and Sin City, here comes Grindhouse, a new intriguing feature film concept opening April 6 from The Weinstein Co. Co-directed by Quentin Tarantino and Rodriguez, the double-feature movie is an homage to the exploitation B-movie thrillers of the `70s. In the visual effects-filled Planet Terror segment, a small town has to deal with an outbreak of dangerous infected people called Sickos.

As on most of his movies, Rodriguez acted as vfx supervisor, splitting the shots between his own Troublemaker digital unit (320 shots) and The Orphanage (106 shots). Ten shots were shared by the two companies. The Orphanage also handled 35 shots for Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof segment. Troublemaker Digital (TMD) comprises of four key artists: Rod Brunet, Chris Olivia, Alex Toader and Drew Dela Cruz. "We are generalists with experience in 3D and all things 2D, including compositing final shots," Brunet says. "In preproduction, we focus on different sequences of Robert's script. Sometimes, that means concept art and storyboarding, but it always evolves into the 3D realm and grows from there. Grindhouse was the first Rodriguez project on which we completed so many final shots."

Most of the animatics were a guideline or visual blueprint to aid in communication on set. TMD tried to take them to a finished look in order to help establish the mood, choreography and pacing upfront.

A New Vfx Challenge

Compared to Rodriguez's previous vfx projects, Grindhouse required very little greenscreen work. Most of the plates were shot on real sets, providing TMD with a new challenge. "In the Spy Kids series, you accepted the exaggerated designs because they were part of an overall stylized look," Toader observes. "In Sin City, nearly all the backgrounds were CG, which made it easier for us to art direct and create. On Grindhouse, we had to do a lot of reverse engineering on the lighting set up and camera work. Everything we did had to match the live-action plate. So, there was less room for artistic license, if you will. It was far more challenging than creating a whole computer-generated shot, which made this project different for all of us."

TMD typically uses several software packages at a time. Notes technology manager Kris Bushover, "We will use whatever we have to make it work. For instance, in tracking, we use boujou 3 and PFTrack by the Pixel Farm. Each one seems to address different problems. We use SOFTIMAGE|XSI 5.1 for 3D and previs work. We have a 116-processor render farm for XSI running Softimage's implementation of mental ray. Additionally, we use Apple Shake for slates and creating QuickTimes for Robert to review. This is all managed by Rush render queue manager."

For Cherrys leg, TMD had hoped to develop an automatic tracking solution, but a keying solution was used instead.

A director with a strong emphasis on visuals, Rodriguez relied a lot on animatics to develop concepts for the movie. "Most of our animatics were a guideline or visual blueprint to aid in communication on set," Olivia adds. "We try to take them to a finished look when we have the time to in order to help establish the mood, choreography and pacing upfront. There was one instance, in the Machete motorcycle jump animatic, where I recreated the practical rig that would be used on set to fly the motorcycle through the air. I set the CG bike up on this animated rig and flew the virtual camera towards it to make it look like the bike was flying through the air. Once Robert approved this, I was able to provide different views and schematics of the virtual scene to other departments to use for the actual shoot."

A Leg One Could Kill For

Planet Terror features a lot of colorful characters, but in terms of uniqueness, no one comes close to Cherry (Rose McGowan), a tough lady who wears a fully loaded machine gun as a leg! Early in preproduction, Toader and Olivia built an in-house gunleg version for animatics and to help in the design. Once the final design was approved and built by the props department, Eyetronics scanned the prop and built a CG model. "Early on, we hoped to develop an automatic tracking solution, but due to discomfort and safety requirements, the L.E.D. cast the actress wore was thrown away, and we focused on a keying solution," Brunet says. "The green boot which lit up in a grid pattern became a diffuse gray stocking with limited leg movement, but did allow a slight knee bend if needed by the actress. Ultimately, we hand-tracked the bandage and gun in XSI for every leg shot. The actress wore an ace bandage that we blended the CG element into. It also gave us a consistent measurement to match."

Adds Dela Cruz, "There wasn't always a clean plate. And even for those shots where a clean plate existed, the camera wasn't motion controlled, so matching the two shots was difficult. Most shots began by removing much of Rose and the background. Clean plates were manufactured in Flame or Photoshop, and tracked into the scene. Then, specific parts from the original plate would be rotoscoped back in. Each background plate posed unique challenges. Shots that one thought would take five minutes took three days. More difficult looking shots sometimes took only hours."

The Sickos look was realized through special make-up effects created by KNB EFX Group with several enhancements by The Orphanage.

In several scenes, Cherry wears a mere table leg instead of her signature gun. Although looking simpler than the gun leg, at least on paper, the effect turned out to be much harder to sell as being real. Animation was made difficult by the fact that the prop connected to the actress above the knee. Any movement by the actress shifting her center of gravity or bending her knee caused the CG object tracking to look wrong. In many shots, a rigid table leg would travel below the deck or floor To overcome this, the final table leg rig gave the team a lot of freedom to lock the tip to the floor, but also allowed a natural hinge or joint under the bandage.

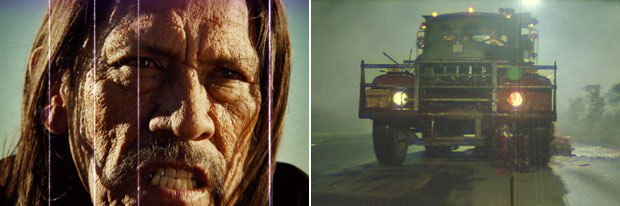

Joining Rose and pals in the zombie bashing is a wild biker (Danny Trejo) who rides a Gatling gun-equipped motorcycle. In a key vfx shot, the character jumps on screen while a massive explosion occurs behind him. "The plate was shot with a rig raising the cycle and actor about six meters off the ground," Brunet notes. "The rig was remotely controlled to rock the cycle back and forward while spinning the wheels. Trejo was placed on top of this contraption and fired blanks out of the gun while a massive pyro ball was detonated from behind at a safe distance. We took that footage, replaced the sky, removed the rig and added CG bullet shell casings on takes where he did not fire the gun." The effect of moving forward in space was achieved by animating in XSI a 3D camera past digital models of power lines, particle smoke and a textured sky dome.

The Orphanage created the exterior shots for a sequence in which the Sickos are chopped up by the rotating blades of a helicopter. This challenging sequence featured CG body parts, blood and many full-CG Sickos.

Zombie Bashing

The Sickos, the cause of all this mayhem, were primarily realized via special make-up effects created by KNB EFX Group. On specific shots, Rodriguez requested that some more life was added to some of the Sickos. "Within Shake, individual shapes were tracked to individual pustules and boils on the skin, and then, with 2D distortion, we made them appear to grow and bubble," Olivia says. "Subtle color correction helped sell the effect and make it appear like either fluid was building up behind the skin or the skin was stretching. We had to be careful with where we applied these effects because if the distortion happened across obvious shadows or highlights in the plate, then it became immediately apparent it was a 2D gag."

Several Sickos enhancements were handled by vfx supervisor Ryan Tudhope and his team at The Orphanage. "Robert's goal was to add interest and movement to the rashes and blisters but in a way that looked like it could have been achieved on set," Tudhope notes. "Some shots were successful with simple 2D compositing approaches, while others benefited from full-CG blister patches that were modeled, animated using blend shapes, and then painstakingly tracked to the deforming surfaces of the actors' faces. In every case, however, the original practical make-up was used as the underlying texture, reference or actual basis for the effect."

The Orphanage was also responsible for a scene in which the hero vehicle flips over and crashes.

The Sickos play a key part in the most outrageous moment of Planet Terror, a sequence where a helicopter chops them up with its rotating blades. All exterior shots featuring the helicopter were assigned to The Orphanage. "There was a practical helicopter on set, which consisted of the wheels and front body section, minus the tail and rotors," Tudhope says. "We gathered detailed reference on set and modeled a matching CG helicopter in Maya. Daniela Calafatello designed a rig that allowed our animators to manipulate various aspects of the geometry in physically accurate ways. The rotor blades, for instance, had both global and individual controls to adjust how much the blades sagged when the helicopter was sitting on the ground, and inversely, bend upwards when the helicopter was suspended in the air.

"We approached the shot in which the Sickos are being chopped up with a variety of techniques. Anytime we can throw more than one technique into a shot at once, it's a great thing because it keeps the audience guessing. For example, once animation was complete, we picked frames where the blades were making contact with the live-action Sickos, and Heather Han painted out the top half of their body for the remainder of the shot. We then added CG body parts, blood, etc., to liven up the event. We combined this with 6-8 full CG Sickos who would take the brunt of the fierce blades. The CG Sickos were modeled by Michal Kriukow to be pre-cut under their clothing, and then simulated by Michael Hall. Michael also added soft-body and cloth simulations of smaller body parts and chunks. Alex Wang handled the look and lighting, and really made the sequence come together."

The Orphanage was also responsible for a scene in which the hero vehicle flips over and crashes. Detailed references were gathered on the actual vehicle for modeling and textures. The animation began with a rigid body simulation of the truck flipping, which provided a near-physically accurate representation of how the vehicle might behave. It was then modified with traditional animation by Sal Ruiz to convey the specific actions that Rodriguez was looking for. Chains and other movable objects were simulated once animation was complete. CG supervisor Mike Janov and td Joel Lelievre handled the overall look and lighting of the vehicle, as well as vfx simulations for the smoke, flying dirt, grass and chains. Mike Terpstra did the final composite.

Rodriguez wanted to reproduce the look of damaged reels and missing frames that was so typical of double feature shows. TMD artfully damaged five of the six 25,000+ frame reels by combining real film damage, plug-ins and stock footage.

The Art of Damaging One's Work

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Planet Terror project was that Rodriguez wanted to reproduce the look of damaged reels and missing frames that was so typical of double feature shows. To this purpose, Troublemaker artfully damaged five of the six 25,000+ frame reels. The damaged look was an amalgam of real film damage, plug-ins and stock footage. "We used actual filmed damage obtained from sources such as Artbeats and Efilm, and couple of plug-ins," Bushover explains. "The main plug-ins were Cinelook for After Effects, Magic Bullet for Avid and Tinder for Shake. Additionally, we shot some practical effects for sparks, smoke, and blood splatter. These elements were all combined in Flame to produce a damage layer that was placed over the color-corrected frames, and then rendered out via an 8-node render farm running Autodesk Burn."

The color-corrected reels were approximately 30,000 frames each -- 10-bit DPX files. They were imported into SGI CXFS Infinite Storage SAN (8TB), and, from there, into the Flame systems. These ran on SGI Tezro workstations and IRIX with 4 TB of local storage each, whereas the Burn nodes were running Red Hat Linux ES3. Additional 2D work was done in Apple Shake (on both Windows and Mac Pro platforms), eyeon Digital Fusion 5 and Adobe After Effects.

"It was not as simple as screening, adding or placing the footage on top of the final plate," Brunet concludes. "We found it looked much more realistic by using a host of compositing techniques. We wrote noise expressions to alter individual color channels randomly over time as one example. We experimented and found all sorts of ways to alter the footage. Robert had us all do passes, and encouraged that we do not share resources. It allowed him to get very different takes on the same idea for his edit. It was a fun process in experimentation!"

Alain Bielik is the founder and editor of renowned effects magazine S.F.X, published in France since 1991. He also contributes to various French publications and occasionally to Cinefex. In 2004, he organized a major special effects exhibition at the Musée International de la Miniature in Lyon, France.