Mary Ann Skweres goes behind the mask to discover the invisible visual effects secrets of The Phantom of the Opera.

Director Joel Schumacher brings Andrew Lloyd Webbers haunting love story, Phantom of the Opera,to the screen with the grand scale and elaborate production values of a classic opera production. Ornate sets, lavish costuming, unforgettable musical performances, sweeping camera moves and subtle visual effects all contribute to the film experience. Cinesite U.K. provided the bulk of the visual effects for the movie, including miniatures, tracking camera moves, compositing and rough previs. David Jones supervised the work in the U.K. for senior visual effects supervisor Nathan McGuiness, owner of post-production house Asylum in Santa Monica, California, which completed more than 150 shots for the film, including the breathtaking opening in which a postcard comes to life.

Phantom was shot in London with no studio being large enough to accommodate the 40-foot long falling chandelier the story required. As a result, Asylum used the inferno system to composite the chandelier into necessary shots.

Discreets lustre system is the beating heart of our film workflow, McGuinness explained in a release. We used lustre to time all the visual effects shots in The Phantom of the Opera, in order to create continuity. With lustre, what you see is what you get on film. It enabled us to control and maintain the director and director of photographys vision. After the effects shots had been timed with lustre, they went to our inferno stations, where eight-10 artists worked on the effects simultaneously.

Visual effects were used to achieve the majestic exterior dimensions of the Opera House and its fiery destruction during the dramatic conclusion of the story. They were also used to create a chandelier element using both the real and miniature chandeliers for the most violent swinging during the interior destruction. Working out of the Cinesite Shepperton facility, model supervisor Jose Granell collaborated once again with production designer Anthony Pratt to accomplish the director and designers vision. An art department liaison served as model unit art director to keep continuity between the departments.

For the exterior shots, the art department in reality only built the square and entrance of the Opera House. Miniatures were used to extend the building past the top of the columns. A majority of the models were built at 12-scale. There was a 1/4-scale chandelier that was used in the transformation of the chandelier from its damaged state back to its earlier glistening glory. For the ending, when the fire blows out the glazed windows, 1/4-scale window elements were match-moved and then were reduced down and tracked into the 12-scale model. That was done primarily for the flame, debris and glass window elements that worked better at the larger size. Granell thinks that most audiences will fail to notice the miniature work. I know the shots inside out. Even looking at them yourself and its your own work, you wouldnt really know. The things that suggest it [visual effects] to the industryyour peers look at a shot and they see that camera move is vast, so they know its probably not for real. Something is going on.

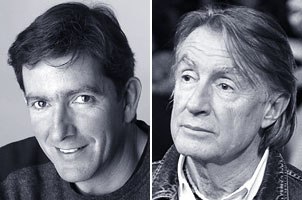

Cinesites Jose Granell (left) was a leader in bringing director Joel Schumachers lavish Opera to life.

The greatest challenge in building the miniatures was the shear amount of detail. Every inch of the exterior façade had some form of architectural detailing gilding, elaborate sculptures, cornices and moldings. Plus, not only did the Opera House have to appear in beautiful pristine condition during its prime, but also in the ramshackle disrepair of its latter days. During a tight turn-around the same miniatures were repainted and damaged to show the ravages of time. Miniatures also helped create the dramatically inspired pullback from the Phantom perched between the wings of an angel sculpture on Opera Houses rooftop high into the sky.

The miniatures footage was combined with the live-action footage to create the illusion of reality by continuing the live-action camera moves. In pre-production, model unit director of photography, Nigel Stone talked with production director of photography, John Mathieson, to get the feel of the show. As dailies came in, Cinesite received tapes of the selected scenes as well as grading (color timing) clips. To match the shots by the visual effects unit to the live-action, the team studied the footage and lighting, the placement of key-lights and practical lights, from sources such as windows and lamps. For Granell the key to seamless integration of the shots is to mimic what first unit is doing. You hope that you are able to create moves and to light in a way that is totally sympathetic to the main unit director and cinematographer, so youre not going off on a tangent and start creating your own version. Ideally people shouldnt notice your signature on the shot. At least thats how I like to work. In a perfect world the main unit would be shooting everything themselves, but they dont have the time to do that. Our job is to take a look at the way they light sequences, the style that they use, the types of moves that the director stylistically tends to go for and then use their approach in our part of the film.

Much of the live-action shots were done on a crane. This style of camerawork made it difficult for the Cinesite team to track shots on set because the cranes werent encoded. Granell explains, In one scene the camera was flying down a wire. It was the equivalent of a big Steadi-cam shot. Or unsteady, I should say. Who knows what the camera is doing up there. When these camera moves needed to be extended in the miniature shoots, they were tracked at the Cinesite digital facility. The Cinesite team used 3D Maya to track the moves. From the selected takes of a shot, main unit dimensions and model dimensions were determined.

The grand chandelier was a key effect that plays a huge role in the story.

Cinesite 3D supervisor, Andy Bull, worked on set. The data he received from Maya was given to motion control. A graph of the move was charted to reveal consistent speed changes, the angle of the climb and the rate of the climb. Data recovered from the tracked move allowed the miniature unit to duplicate scale moves on the 12-scale miniature. But there were certain pitfalls that the team had to be careful to avoid when working with models.

The 3D team came in and took key dimensions and measurements from the miniature of the Opera House as it was being constructed. By the time the model unit was scheduled to shoot, a fairly detailed three-dimensional wireframe of the Opera House had been created. It was used for the model unit to previs their own shotsto check out the camera moves that they needed to mimic in order to extend the original camera moves. It was an invaluable tool for Granell, Wed take over the move to make the shot last longer. I could look at the original moves on the wireframe. It gave us an idea of how far back we would have to track on that model and how high we had to rise above it. I have heard of instances where people built miniatures and no ones paid attention to scale. Then you get on the set and suddenly you realize when you go to playback a scale move, your camera ends up outside the stage. You have a big problem. We like to plan ahead as much as possible here.

Using miniatures instead of computer graphics for the set extensions draws on classic visual effects techniques aided by technology. The use of miniatures is a decision the production has to make which is not always practical in the real world. The benefit is that the shoot is done using all real elements. Although it is done at a smaller scale, it is done in the same manner as if it were done during the live-action shoot. If a hand-held camera is used on set, then a hand-held camera can be used with the scale miniatures. For computer graphics, the virtual camera can mimic the live-action move, but has a different feel for the traditional camera operator. The computer can do more extreme movesfrom outer space all the way into an extreme close of an eyebut these moves by their very nature can lose a sense of reality. The realistic techniques used in a miniature shoot are generally more likely to look real by the nature of their limits and the comparable limits of live-action shooting.

However, the computer has become a standard method for finishing. When the 3D digital department received miniature shots for compositing, they used the beauty shot as a guide. As they started putting the miniatures into the live action, they broke the footage down into separate parts and tweaked the lighting. This allowed them to dial in higher or lower exposure values for all the different elements. Granell concludes, Effectively, it gives them total control in post-production, which is the accepted way now. Thats the way weve been working for a long time.

Mary Ann Skweres is a filmmaker and freelance writer. She has worked extensively in feature film and documentary post-production with credits as a picture editor and visual effects assistant. She is a member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild.