In the last installment of his exclusive Polar Express production diary, David Schaub breaks down characters and performances that were keyframed.

The Polar Express animation supervisor David Schaub.

This is the final installment in VFXWorldsThe Polar Express production diary. Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

From the very beginning, it was clear that certain portions of The Polar Express would have to be keyframe-animated. We had wolves, an eagle, caribou and reindeer that obviously couldnt be directed in MoCap. There was also a fantastical sequence where we follow the ticket as it flies out the window of the train, which also didnt qualify for motion capture. The nature of the Smokey and Steamer characters were by design more exaggerated and cartoony than real people, and thus required the kind of freedom and control that keyframe animation affords.

As the animation supervisor on this project, it was a great opportunity to create characters and performances in much the same way weve done in the past.

The Ticket Ride Sequence

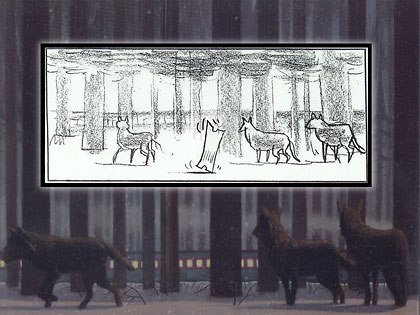

The real motivation for the ticket ride was the illustration in the book where we see an image of three wolves looking at the train. (Every illustration in the book is represented somewhere in the film.) We needed some reason to establish that shot, and Bob Zemeckis thought, lets do the ticket ride, where Chris loses the ticket and it floats around and lands in the forest and these wolves come along and strike the same pose as the book.

Bob Zemeckis imagined the ticket ride sequence as a crazy journey and he gave the animators and digital artists carte blanche to go off and explore. All images © 2004 by Warner Bros. Ent. Inc.

Bobs imagination went from there, and he wanted to turn it into a grand bit, where the ticket goes on a crazy journey his inspiration just spilled out. From the outset, Bob turned to us and told us to start playing, to start executing stuff. He really gave us carte blanche to go off and explore, with the idea of pitching new ideas as we went. It was an exciting exploratory process.

We were given some rough drawings and story ideas that his storyboard people had mocked up, and we took those drawings and set it up as a real shot. The unique thing about the ticket ride is that it is all one shot no cuts from beginning to end. In the original cut it was five minutes long we ended up with 2.5 minutes.

Stephane Couture was the first animator to start work on the sequence, creating wolf cycles. I also started animating early on with the wolf performances as they run into frame and strike the pose from the book. We did some tests and pitched some ideas to Bob about how the ticket would move. He wanted the ticket to move naturalistically, so once we got that feedback, we rigged the ticket to support that idea.

Because it was one long move, the sequence was assigned to Stephane. Hes designing the camera move and the ticket animation to make sure it stays in frame and make it look like the camera is following the ticket and not the other way around. As other animators got involved, theyd do wolf runs and wolf business there were a lot of cycles of wolves, running, jumping over obstacles, tripping. Stephane would get these animations, time them, compose them and lay them out with the camera he was working with. It was a constant back and forth, because every time Bob saw an iteration, hed make changes, and that would change the composition. Stephane would have to go back and reposition the wolves so that they are framed in an appealing way. Once they were back in frame, they might run into a tree, for example, so wed adjust the animation so theyd run around the tree or jump over that log.

Once the ticket goes past the wolves, were out over the water where the eagle picks up the ticket. The eagle grabs the ticket out of the air and flies under the bridge, to bring the ticket to the nest where the eaglet is. Were working on this its about four months into animation at this point and Bob has a new idea: Wouldnt it be funny if the ticket had a life of its own, alive like Aladdins carpet? The whole thing is a dreamscape anyway so its not completely preposterous. It just so happened that we had Randy Cartwright on staff, who was the lead animator on the carpet in Disneys Aladdin. The casting choice was an obvious one, and he took over that small task of bringing the ticket to life.

Of course, we had to throw out everything beyond where the ticket lands in the woods. Now weve got a ticket that behaves differently. Randy, being a traditional animator, produced a series of 2D pencil tests that we would lay in over the top of the wolf animation wed already done and try to get an idea of how the ticket would behave. J.J. Blumenkraz rigging department re-rigged the ticket to support that motion.

The motivation for the ticket ride was the books illustration of wolves looking at the train. Zemeckis wanted the lost ticket to float and land in the forest, where the wolves arrive and strike the same pose as the book.

We then went through a series of board developments, for actions such as the ticket jumping onto the wolf and moving from tail to ear, like a cowboy. Then the ticket turns into a flapping butterfly to try to get back on the train, but fails. Once we got the ticket into the eagles nest, we discover its three times the size of the eaglet. We were able to cheat the scale of the ticket, especially at the point where it gets crumpled up so the eaglet can swallow it then spit it up as a crumpled ball. During its fall from the nest, it origamis itself into a paper airplane and takes off full steam after the train. It hears the train whistle, gets disoriented, hits a tree and falls down to the train tracks where it gets stuck. This is where the bunny comes along and tries to dislodge the ticket.

Roger Vizard did all of the eagle, eaglet and bunny animations. Again, Stephane compiled all the animation elements and orchestrated all the camera moves to support that animation. When it was naturalistic, Stephane handled the ticket and worked the camera to the ticket. Once the ticket was alive, rather than being naturalistic, it was animated by someone else in little chunks. Now hes receiving animation from Randy and a couple of other animators, and having to work that into his camera moves. The big master environment is what Stephane was in charge of.

Bob loved the bunny animation so much so that he first asked us to expand it to a pair of bunnies, and then a whole family of bunnies. We tried to deliver stuff we could sell to him, that was actually working so we gave him sequences that werent lit but were pretty far along. We incorporated all kinds of little gags that we were trying to sell him on.

All through this, we had a lot of freedom to develop and try ideas. Hed say make it two bunnies, and we had to come up with ideas here of how to get them to interact. We thrived on this every new idea he came up with, as crazy as it sounded, was a wide-open canvas for us to do creative things.

Then there was another big switch-up. Three months before delivery, Bob ultimately concluded that this ticket-being-alive thing, no matter how much fun, just wasnt working for the movie. Its time to go back to the naturalistic ticket on the wind. The fanciful approach was a huge risk from the beginning, and he knew it. However, this is Bobs creative process. He knew it was worth a shot. Even with all those months invested, he is also not afraid to strip it down and start again. We had three months to complete this sequence and revert back to the original idea. Stephane re-inherited the ticket animation for the entire piece. It was a technically monstrous challenge to wrangle everything, because the smallest camera adjustment in a world that vast throws everything off. What was originally expected to be a three-month commitment for Stephane, turned into a project that lasted the entire duration of the show.

Steamer (above) and Smokey were modeled in pre-production and built from scratch digitally. When it was decided they were going to be keyframed, a rig was built that allowed animators to animate traditionally.

Even though the ticket ride is one shot, we divided it up into five digestible chunks, based on convenient transition points: one starts the moment the ticket leaves the train to just before it lands in the forest, with the empty sky as a backdrop. Another was the moment the eagle snatches the ticket, and another was the moment it leaves the nest. CG supervisor Mark Lambert was heavily involved in working with Stephane to define these transitions and manipulating the camera in this huge environment.

With only three months to re-do the sequence, we made use of everything we could. The camera and the ticket were completely re-animated, but we definitely made use of the wolves, which we were able to adjust. The eagle didnt have to change. The eaglet needed a little bit of work. We were able to re-use a great deal of the animation wed already done and hand the whole shot over to lighting with just enough time to spare.

Steamer and Smokey

Bob wanted these characters to be the films comic relief and they were definitely proportioned that way the Three Stooges minus one. Steamer and Smokey were voiced by Michael Jeter, and the original idea was to motion capture him. Jeter would be playing an eight-foot tall character and a four-foot character. Due to the huge size discrepancy, it was impractical and ineffective to retarget motion data to those proportions. The dynamics and physicality simply did not translate in a believable way. Since these characters were such caricatures to begin with, we thought that keyframe animation would be the best approach. We could make them more exaggerated not with traditional cartoon timing where physics doesnt apply, because physics did apply to fit them into this world. But we could create these kind of cartoon-like characters through extreme broad poses and wacky gags with a physicality that worked within this environment.

The characters had been designed and modeled months before, in pre-production, built from scratch digitally by our modeling group. Originally these characters were rigged for motion capture, but when it was decided they were going to be keyframed, we needed a rig that would allow animators to animate traditionally without all that MoCap overhead in the rig. That included facial animation. We had a motion capture-based facial animation system that was impractical for keyframe animation. We would have to manipulate 20 muscles to get a simple smile.

Instead, we opted to go with an entirely different facial animation rig, one that was being developed for Sony Pictures Imageworks sister company, Sony Pictures Animation. Doing this required stripping out what was there and rebuilding with a completely different facial animation system, but I was set on using it because I knew how much time and effort it would save.

A song-and-dance routine featuring Smokey (above) and Steamer was created but never included in the final cut. It was a funny slapstick piece of animation that helped to explain the characters.

The very first thing we did with these characters was a song-and-dance routine that didnt make the movie [but can be viewed as a bonus feature on the DVD from Warner Home Video, which streets Nov. 22]. Once again, we had carte blanche. They had recorded Michael singing the song and we explored the gags we could achieve with these characters. We made it into a really funny slapstick piece of animation and the entire process allowed us to figure out who the characters were. Even though it ultimately didnt make it into the movie, this was our character development piece and it made Bob realize what we could achieve with this style of slapstick animation even in this reality-based world.

In addition to that song and dance, another part of this sequence was explaining the ghost story behind the hobo, using shadow puppetry. It was an interesting idea: the fire of the furnace was the light source and the tarp between the engine and the coal car was the screen. We were given the audio track of Michael Jeter telling the story and Bob said, do it like kabuki theater just tell the story with shadows. It was a great opportunity for animator Roger Vizard and me to craft the equivalent of an animated short. We animated it and executed this piece using virtual cardboard cut-outs, playing with light to create interesting transitions. Bob loved the storytelling aspect but thought that the perfectly crafted cut-outs implied that theyd told the story before. He wanted the story to be spontaneous, told with tools youd find in an engine room along with their bodies and hands. The second pass ended up very natural and organic and we all loved it. But, for restrictions of the films final length, it got cut.

Animating Smokey and Steamer was a real chance for us to have fun, because Bob gave us broad stroke direction for each one of the bits theyre featured in. Working with Roger and Renato Dos Anjos, storyboard ideas were produced and pitched to Bob before executing them. Since the song-and-dance intro piece was cut from the film, we were stuck with the dilemma of a unique way to introduce the characters. We pitched all different kinds of ideas, which finally evolved into the shot on the front of the train where Smokey lowers Steamer down by his beard to change the light bulb. That was actually one of the last shots delivered.

Another deleted sequence explained the ghost story behind the hobo using shadow puppetry, as seen in the painting above. The furnace fire was the light source and a tarp served as the screen. It had the feel of kabuki theater.

It was that way with all the Smokey and Steamer scenes. He let us go for it. Wed have big brainstorming sessions with the boards. This was Bobs comic relief as well, and I think he always looked forward to the new batch of storyboards. Once he latched onto an idea, wed go back and block out the performance along with a rough camera. Roger, Renato and I were the lead animators. The first pass was very rough, but enough to get performance and screen direction notes so that it could become a real shot (or series of shots) and taken to the next level.

The next step would be to cast it to an animator, shot by shot. Wed typically block the entire chunk, maybe as one big shot, and then Bob would break it into three shots. Once it was broken into shots, it would be executed by one of the three lead guys or passed around to other animators on the crew. There were about eight keyframe contributors at that point.

That sequence on front of the train introduced Smokey and Steamer, and led into the big caribou sequence. To get the caribou cleared off the track, the conductor realizes if he pulls on Smokeys beard, Smokey lets out a scream like a steam whistle that the caribou respond to. Thats another wacky gag that doesnt sound funny or doesnt even play funny in storyboard form, but you can do a lot with it in animation and facial expressions to make it come off very funny.

The big cotter pin gag came next. Smokey and Steamer have lost the cotter pin that holds the throttle mechanism in place, and the train spins out of control the sequence known as the roller coaster ride. Rather than applying the brakes, theyre looking for the cotter pin to cut off the throttle. In the process of the roller coaster ride, they retrieve the cotter pin and Steamer ends up swallowing it. Now what do you do? You know were not going to get the pin back. We drew up an idea (and actually executed it) where Smokey grabs the coal shovel and smacks Steamer in the back to dislodge the pin - then it flies out the window lost again. Now what?

Editor Orlando Duenas, threw out the idea that the pin sticks in the frozen lake and its that little pin that causes the lake to crack, which leads to the complete destruction of the lake. Bob thought it was a great idea, and just like Disney used to when an animator came up with a really good gag idea, he threw out $5 on the table for Orlando.

These concept sketches from the roller coaster ride sequence were used to pitch to Zemeckis. The creative team came up with the idea that Steamers cotter pin causes the lake to crack and that Smokey (above) gives up a prized hairpin to stop the

We still had to figure out how to stop the train. We boarded up a series of ideas, based on the idea that Smokey had other cotter pins on him but didnt want to give them up. In one idea, he uses them to hold up his suspenders so when he pulls one out, his pants drop. Another was that he had a collection of hairpins in his hair, and when he takes his cap off, he reluctantly gives up one of his prized pins and sticks it in the mechanism to stop the train. That was the winning idea.

Conclusion

The Polar Express has rightly so gotten a lot of attention for the innovations in using motion capture for an entire film. But to me its just as interesting that keyframe animation played an important supporting role, to create segments of the movie that were either impossible to MoCap or better done keyframed. All of these segments benefited creatively from what we were able to bring to them with keyframe, adding whimsy and fantasy, comedy and realism. Working with Bob was a true creative partnership. We all felt lucky to be in a position to be invited to contribute substantially to the creative direction of the picture and execute animations that helped to bring The Polar Express alive and make it the unique film that it is.

Since joining Sony Pictures Imageworks in 1995, David Schaub has served as an animator, animation director and supervisor on a number of projects. He is currently working as the directing animator on Surfs Up, Sony Pictures Animations second 3D-animated feature. He recently completed work on The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe as the animation director for Mr. & Mrs. Beaver, the fox and wolves.

In 2004, Schaub worked with director Robert Zemeckis as the animation supervisor on The Polar Express, for which he and his crew received a VES nomination (Visual Effects Society) for Steamer, one of the keyframe- animated characters in the film. He was a supervising animator on Stuart Little 2, receiving a VES Award for Best Character Animation in an Animated Motion Picture. His other film credits at Imageworks include the Academy Award-nominated Stuart Little, Cast Away, Evolution, Patch Adams, the Academy Award nominated Hollow Man, Godzilla and The Craft.