Virtual filmmaking is energizing the industry and leading to a more creative climate for directors and other filmmakers, according to Robert C. Powers (Avatar, Tintin).

A camerman stands inside a soundproof camera booth with a Vitaphone camera, circa 1926. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The dawn of a new "virtual filmmaking" age is upon us. Sparked by the pioneering work of Bob Zemeckis on The Polar Express and Beowulf and amped to the extreme to create a realtime director-centric workflow by James Cameron, Rob Legato and team for the upcoming Avatar, this new evolution of the filmmaking process is energizing the Hollywood industry. Having worked on a couple of these bleeding-edge film projects (Avatar, Tintin) with many of the industry's' leading filmmakers, artists and technicians has allowed me to witness and contribute to the development of this new virtual filmmaking system that will likely lead the moviemaking process over the coming decades. The virtual filmmaking process is an amalgamation of traditional filmmaking, CGI, visual effects pipelines, previs workflows and realtime computer gaming technology. Virtual filmmaking combines the best parts of all of these previous traditions in a unique way to create something immensely useful and creatively liberating for the director and other artistic team members. Although I can't elaborate on the specifics of any one system, I'd like to briefly touch on the technological progression toward the virtual filmmaking revolution in general and point out some of the innovations of this new system.

Technical limitations imposed on filmmaking are nothing new. The art form endured an earlier "dark-ages" period when it struggled with the coming of sound and the introduction of the first color film stocks. These technological advancements actually changed the way that films were made for short while due to the often overwhelming limitations they imposed. The fluid moving cameras of the silent film era had reached an almost poetic height only to be temporarily restricted when cameras suddenly required bulky soundproof enclosures to eliminate the noise from their mechanisms. Actors that previously had freedom of motion now found themselves speaking into potted plants or telephones, which concealed a hidden microphone, as in the infamous Warner Bros. film The Lights of New York produced in 1928. In addition, there were three different, non-compatible sound systems competing to become the sound standard. These were the Vitaphone, Movietone and Photophone systems and much like the current format wars of today they were all backed and supported by different studios and groups. Sound familiar? Later, in the 1950s, the heavy lighting requirements of early color film stocks imposed limitations on the cinematographers and production designers and also influenced and changed the final imagery of the films themselves. Given time and ingenuity, these limitations were overcome and the art form once again was able to flourish.

Similarly, our current visual effects and CG filmmaking evolution has been technologically shackled throughout its first several decades of development. Filmmaking has gone through a tremendous change in the last 30 years with more and more films involving elaborate visual effects sequences with complete digital environments and characters becoming commonplace. Often the films are so heavy with vfx that the effects themselves almost become the "star of the show." Filmmakers and actors comfortable working on a live-action set in the traditional way have increasingly found themselves alienated from the living, breathing, realtime discovery process that was previously inherent in the moviemaking workflow. Many wonderful "happy accidents" and creative discoveries were born from the director, cinematographer and actor's interaction within the "real" environments on the live-action set and this allowed these creative individuals to be fully "in the moment." These types of creative inspirations cannot easily be planned or anticipated and attempting to do so often produces results that are hollow or false.

For the filmmaker, virtual filmmaking could easily be seen as a long overdue correction to a system often hampered by the inherent limitations of traditional visual effects pipelines and CG technology. As the fully CG films have evolved, they have inherited the benefits and limitations of a traditional visual effects pipeline. With all of the fantastical imagery that these pipelines have allowed, they have also often stifled much of the immediate, organic discovery and replaced it with a slow and laborious process that required the director to wait weeks or months before seeing how a sequence would actually look in the final film. As a result, this slow turn-around time for the visual effects often limited or altered some of the decisions and discoveries that would have occurred had the shots been created in the traditional live-action way.

A "fix it in post" attitude often prevails with the larger visual effects houses who know that if given the time and money their large teams of animators and technicians will eventually turn over visually impressive shots for the film. This works great for the visual effects houses with their regimented technical pipelines, but it isn't the most ideal situation for the director, actors or cinematographer, who often make many profound artistic discoveries "in the moment" and are inspired by having direct interaction with the lighting, sets, props and other characters. Give these creative individuals something tangible that they can see, touch and interact with and they will flourish: Thus, the emergence of the virtual filmmaking process.

One of the biggest challenges faced by CG filmmaking and visual effects has been to duplicate all of the subtle accidents and unpredictable events that happen in the real world and make a shot look alive and believable. The barely perceptible twitch in a character's eye or the way the characters move through lighting on a set can be taken for granted on a live action movie, but often these things require weeks of painstaking work by numerous individuals when replicated in CG. As a result, many of the subtleties of the real world are often lost, leaving the audience with a feeling that something is missing or wrong with the shots.

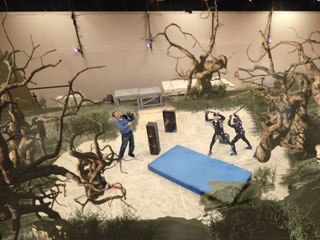

On a MoCap stage, traditional moviemaking elements are replaced with strange suits, flat-gray sets, harsh lighting and empty stage walls. Unless noted, all images courtesy of Robert Powers.

At least on a traditional live-action film the director and actors have real world, tangible cues from the lighting, real sets, costumes and props to immediately interact with. On a motion capture stage, however, these elements have been replaced with strange multi-colored, skin-tight MoCap suits, flat-gray sets, harsh bright lighting and empty stage walls. In this strange environment, these very creative people have often found themselves alienated and distanced from everything that they know. As motion capture emerged with such pioneering companies as Giant Studios and became common throughout the 1990s, it revolutionized CG character motion because it allowed all of the subtle motion cues of the living actor's performance to be placed onto a CG character. The CG "dancing baby" is an early example of this motion capture technology being applied to a CG model and producing something that moved more lifelike than previously animated characters. When I worked as a CG animator on the first season of the Ally McBeal television series, I remember being surprised at the public's reaction and level of attention on the 3D baby. Looking back, I'm sure that the novelty of the character being a baby had a lot to do with this but also I think the public was responding to the more lifelike motion capture that was driving the CG baby model. At the time, it was unique and interesting to see such realistic motion on an obviously computer-generated character. Capturing the direct motion of trained, professional actors was a huge step toward reconnecting the CG filmmaking process with the real filmmaking world, but it was still fairly alienating because of the lack of realtime feedback of the performance.

Shortly after body motion capture emerged, there was also a push for facial motion capture, which recorded the subtle facial muscle movements of the actor's faces and mapped them onto a CG character face. Both body and facial motion capture have continued to evolve and are currently at a much more sophisticated level than even five years ago. Both of these forms of motion capture technology have been instrumental in bringing the human actor forward into the emerging CG filmmaking process. After all, acting is a very complex craft that many individuals spend a lifetime perfecting and it would be a shame to disenfranchise this amazingly talented group of people from the process and replace them solely with animators and CG technicians on productions where more realistic performance is required.

Virtual filmmaking gives creative filmmakers something tangible that they can see, touch and interact with.

This motion capture process is great for involving the actors and their craft but what about the director? To replicate the director's experience on a live- action set there were still some things missing from the CG filmmaking pipeline. The director's point of view and immediate creative impulses were still not accounted for anywhere in the motion capture process. It was often not conducive to natural situations with real visual stimuli for the actors and director to bounce off of creatively. If a lighting effect, digital environment or animated creature isn't present at the time of shooting, then it becomes much more challenging for the director to block the shots and get inspired performances from the actors. These wonderfully creative people are all required to "imagine" what it would be like if the tracking marker dot on a C-stand was actually a creature attacking them -- which is a much different experience than actually interacting with something in realtime.

The next huge revolution occurred when the director's point of view was finally brought into the motion capture process with the virtual camera concept. The virtual camera offers a way for the director to experience the virtual environments, sets, props and characters in much the same way that a "first person" video game player is able to move through the game levels in realtime and interact with the characters, props and environments in the video game engine. In addition to giving this realtime feedback to the director, this advancement also allowed the director's physical camera position and settings to be tracked alongside the motion capture of the actors and allowed his immediate "in the moment" interaction with the actors' performances and the camera. The handheld camera was back on the scene -- and the hand holding was that of the director himself. No longer did the director have to solely rely on legions of CG animators and the visual effects houses to create keyframed and often stilted camera moves.

In addition, a "virtual camera" allows all of the features of a real world camera with none of the real world limitations. Changing focal lengths, zooming and "virtual crane moves" are all possible and on call at any moment. This wonderful advancement started appearing in SIGGRAPH papers from the late 1990s and was pioneered for film and television applications by companies such as InterSense Inc. among others.

And its emergence encouraged a stronger artistic consciousness in the virtual production pipeline by helping to integrate the art direction, cinematography and realtime visual feedback of the sets, virtual environments and characters during the virtual camera "shoot." You can track the motion of the actors and the director's camera, but if you can't see an appealing environment and atmosphere through the camera in realtime then the organic "in the moment" discovery process is crippled. Early tests of most virtual camera systems included crude representations of the environments and characters at best and lighting and shadow were almost entirely missing due to optimization issues, unfamiliarity with the software and system calculation overhead. Being familiar with the current motion capture tools, 3D software and hardware and the limitations of those applications, it became clear to me what could be achieved by combining the strengths of game engine optimizations while packing in as much of the production design and lighting information for realtime feedback for the director.

Additionally, once those basics were covered, why stop there? One of the major strengths of virtual filmmaking is the additional realtime flexibility that it allows for the director and creative team above and beyond that of previous filmmaking workflows. Some of the techniques that I and other team members stumbled upon while working under fire led to the development of creative organizational systems for the digital assets, which allowed easy re-use, interactive manipulation and unparalleled creativity in realtime for the filmmakers. The goal was to make the virtual props and environments serve the needs of the directors and their virtual camera while offering as many options as possible as quickly as possible. The techniques that emerged could easily fill an article by themselves and often required thinking way outside of the box.

The combination of these various technologies equals so much more than the sum of the individual parts. Used together, the actor's facial and body motion capture, the director's virtual camera data and the realtime artistically appealing feedback of interchangeable 3D virtual sets and characters created by the virtual art department all combine to give a realtime, visceral experience back to the director, actors and the rest of the creative production team. More creative decisions can be made "in the moment" and on the "virtual set" with the "virtual actors" in much the same way that directors are accustomed to on a live-action film shoot. By solving many of the creative and logistical problems early and directly with the director and actors during the virtual production, process time and money can be optimized and the problems aren't unnecessarily sent down the production pipeline to create wasted effort on shots that don't work and require endless feedback and more expensive post-production time to fix. On top of replicating a live-action production workflow, the virtual workflow allows additional options for the director that would likely be impossible on a live-action set. The realtime immediate feedback of all of these elements is the overriding theme that once again heralds the dawn of a new cinematic era, unshackles the filmmakers and offers a re-emergence of the organic, living, breathing, filmmaking process now reborn as "virtual filmmaking."

A graduate of the USC Cinema Production program and AFI Fellow, Robert Powers has most recently worked on stereoscopic projects as animation TD and/or virtual art department supervisor for directors James Cameron ( Aliens of the Deep and Avatar) and Steven Spielberg ( Tintin).These have been for Earthship Prods., Lightstorm Ent., Pandora Film Services Inc. and DreamWorks Prods. LTD.Powers specializes in early design/animation conceptualization and virtual filmmaking workflow setup. You can contact him at rob@robpowers.com(link sends e-mail).