Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman takes the challenge of address growing discontent from animators toward the industry by asking the question -- if animation is hell now than what was it 25 years ago?

Does Anibator represent a new season of discontent in animation? Courtesy of iStockphoto.

The year 2007 marks my 11th year of writing (largely) about the relationship between animation and popular culture, and the fact that I am still mining the topic amazes me. Whether the discourse is about the rise of adult-oriented cartoons or the failures of deconstructive critique in analyzing mainstream animation, the topic of animation's role in American society appears to be inexhaustible.

In truth, there is no art form as plastic or as mercurial. Animation's evolution from slash technique, ink, and rice paper to Maya 8.5 kinematics is one of the most amazing ever experienced in the history of art, and it dazes one to think that such a leap was accomplished in just over one hundred years. It took twice as long for Renaissance art to evolve through Giotto di Bondone to Masaccio to Michelangelo's magmum opus in the Sistine Chapel.

Yet, at the same time, all is not harmonious in that world. Animation is a vulnerable art form. At its most accessible, that is to say, as seen on screen and television, animation is at times forced into an unholy marriage with executives that see only a bottom line where creators see a masterpiece. The battles against economic forces that send animation overseas, against labor conditions that necessitate constant watchdog efforts by unions, and clashes with market forces determined by ratings can make animation a difficult and frustrating avocation. There are other difficulties as well.

Independents struggle for recognition outside of festivals, and many of them pin their hopes on pitches to mainstream studios, which can be a soul-numbing experience. Many animation schools seem to need more courses in history and animation appreciation, which could help aspiring animators develop ideas that spin off from some of the greatest concepts of the past. Animation execs and accountants do not always understand the creative end of animation before handing off projects to the unproven and less prepared hopefuls based on a single drawing or sketchy concept. Both suit and artist do not always understand that selling points such as "edgy" might need more specificity before time, effort and money is invested into a pilot.

Anibator takes the animation business to task and has poured vituperation all over the industry. The blogger attacks some of animation's brighter lights, such as John Kricfalusi (above) for his dogmatism.

The past couple of months saw the rise of a notorious blogger known as the Anibator, and s(he) takes the animation business to task on all these points and more. This individual, who retains anonymity, has poured vituperation all over the industry, claiming to be the only soul daring to expose the dark side of the cartoon business. If nothing else, the Anibator is an equal opportunity antagonist, challenging both this website and Animation Magazine to dispute his/her bitter claims about the industry, while also harrying some of animation's brighter lights, such as John Kricfalusi, for his dogmatism.

In the Anibator's view, a modern career in animation is roughly equivalent to the Inquisition as conducted by Philistines; it can only end in disappointment and futility. As s(he) avers, "I work in animation. I am in hell." This entity's bitterness was such that the Anibator became a cause célèbre among animation fans; some people submitting comments to the blogspot treated the Anibator with disdain, challenging the blogger to go out and improve things if s(he) didn't like them.

An equal number, however, responded to the blog with great relish, avidly naming shows that they considered to be the crippled and enervated products of an art that had sold its soul to incompetent, uncaring businessmen. It is not my intent to glorify or defile the Anibator. I don't agree with the Anibator's every conclusion, nor do I believe American animation to be corrupted beyond redemption. I believe that the Anibator must passionately love animation, and that is worth much. Where I most strongly contend the Anibator's viewpoint is through an overall perception of historical context, and that might well be where both s(he) and some (but not all) of the Anibator's supporters may be missing the point. The truth is, animation has never been an easy business to work in, whether one focuses on 1927 or 2007.

Before exploring this further, I must first ask: Is there a business extant, which is not at times hell for its workers? How many degrees is Dilbert actually removed from the truth? As I write this, there are legions of American workers struggling under execs who may be distinctly less gifted in intellect than them. There are corporate dictators, untalented decision-makers and managers who substitute MBA courses and the managerial equivalent of self-help books for true leadership talent. There is no guarantee of safety from outsourcing, layoffs and paring from the payrolls through mergers, and this does not even begin to take into account those of us in relative safety who dislike our jobs, our non-managerial co-workers or who would -- and do -- change careers out of dissatisfaction or a yearning for something more rewarding.

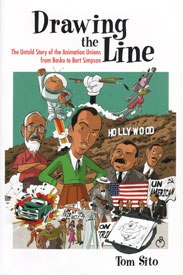

There has been an excellent publication of late, Drawing The Line, by Tom Sito, who is no stranger to the issues faced by animation's labor unions past and present. Animation personnel of yore were traditionally underpaid, overworked, exploited and, in some instances, watched characters they created add millions to the coffers of the studios they worked for while their own wallets remained thin. The only reward was continued employment, and even this was subject to the capricious whim of management. Every major studio suffered strikes by animation workers, and many times the labor end came off the worst.

Is there a business that is not at times hell for its workers? Tom Sito's Drawing The Line exposes past animators who were exploited and watched their creations earn millions for the studios while their own wallets remained thin.

When the theatrical animation industry shut down at the end of the 1950s, the industry's best talents went into television programming or advertising, and their creations were always animated. If this was (is) such a god-awful business, why did they bother? And what indeed kept them there, or drew new talent into the business? Were the network execs who greenlit Laverne and Shirley in the Army or Lassie's Rescue Rangers in the belief that they were entertainment any more astute or prescient than the ones who greenlit Class of 3000 in the belief that the front man for Outkast must have skills equal to, say, John Dilworth's? Somehow, I doubt it. Yet, even as the jobs flowed overseas and runaway animation became the norm, the veterans stayed on and students swelled the halls of animation schools worldwide.

For some reason, not entirely economic, animation endured. Thrived. Some of the greatest animation ever produced, honored by both the Anibator and Kricfalusi, came to life even as union and studio crossed swords and picket signs were being painted (or newly laid aside). To be sure, there were disillusioned souls who later went into commercial art, graphic design, independent work or, in some cases, laid their pencils down for good, but, for the most part, people stayed with the medium.

It is certainly a fact that these jobs paid the bills and fed the kids, but it is hard not to believe that those who worked in animation genuinely loved what they did and enjoyed the creative challenges of the medium. Not to mention, the wonder of making one's living through artistic expression. This, indeed, is where the Anibator's bile breaks against the twin rocks of creativity and passion.

I concede that animation can be a difficult way to make a living, and that there are privations and frustrations to be borne for creative individuals in the industry. The Anibator does offer some wise counsel for those that choose that path. Those that truly want an animation career, however, will continue to brave the minefields of execs who are untrained in the medium, make heartfelt pitches that fail and experience the agony of seeing unoriginal and derivative shows promoted over better material. Animation has its discontents, but the truth is, the medium as both art and entertainment will go on, and will continue to leave its lasting mark on our culture.

Fred Seibert can be credited with improving the animated series with his concept of making a series of one-shot, creator-driven cartoons.

If I had my choice (and I certainly don't), I would rather work in animation today than 25 years ago. Mainstream animation was moribund, animated features were few, CGI did not exist, runaway animation was rampant and the future of the industry seemed to be a cesspool of half-hour long animated toy commercials. The influence of anime was negligible, there was little diversity in the creative pool and the concept of creator-driven cartoons belonged solely to the realm of independent animators. I personally do not know how long the Anibator has been around. Perhaps s(he) carries permanent scars from those days. I would rather look at how things may be changing.

In the early 1990s, Nickelodeon decided to develop original, creator-driven animated series, and, in so doing, improved the medium greatly. Some execs did not grasp this concept or adapt to it. Fred Seibert, who wanted to make an entire series consisting of one-shot, creator-driven cartoons in the hopes of finding a hit, did. Seibert originally failed to sell Nickelodeon on the idea, but when he went to Turner's Cartoon Network (and Hanna-Barbera), he was able to institute the idea. The resulting series, What a Cartoon! (1996), established several popular, high-quality series and brought a new generation of animation talent to the fore.

Seibert eventually did replicate his success at Nickelodeon with Oh Yeah! Cartoons (1998), and, most recently, with the soon-to-be-aired series Random! Cartoons. All of the shorts are creator-driven, produced with more guidance than interference from execs, and the talent pool contains more women and a wider range of ethnicities than previously seen in any one series. It is expected, and probably inevitable, that some of the shorts will go to series and become wildly popular. It is also to be expected that some of the personnel involved in the three series mentioned above will eventually become animation execs -- the very ones that are more likely to bring about a future revolution.

Martin Goodman.

Is animation doomed, as the Anibator insists it is? My answer is yes -- but with a qualification. This era of animation is doomed -- doomed to change. Just as the era of India ink-and rubber-hose limbs was doomed. Or the era of the theatrical cartoon. Or the era of in-house animation studios. Or the era where Disney was the only viable producer of animated feature-length films. Or the era in which computer-generated animation produced nothing more sophisticated than the vehicle in Tron. Or the era prior to the influence of anime on American and European animation. Or the era before creator-driven cartoons (of whatever quality) began to dominate the mainstream.

The decade 1997-2007 is a snapshot in the history and evolution of animation, not a death march to its conclusion. As in every era, there is that which is putrid and that which is great, and what is needed is a historical perspective that includes an appreciation of cyclical change. Without that, it might be easy to fall into the trap of seeing conditions as they are today as an inevitable pattern of dissolution and entropy. Be of good cheer, Anibator. Your writing reveals you to be bitter, but also intelligent and passionate, or you would not have bothered in the first place, and I salute you for that.

However, animation is never doomed until human creativity is doomed. Even the entertainment marketplace and the suits who desperately try to corner it cannot defy that fact.

Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman is a longtime student and fan of animation. He lives in Anderson, Indiana.