In Part 3 of this series, Ellen Besen discusses the impact of new technology on performance and the future roles of technology, new and old, with former Disney animation artist Charlie Bonifacio and former Pixar animation artist Stephen Barnes.

Be sure to check out Part 1 and Part 2 of the series Make It Real.

Stephen Barnes, a classically trained artist who has worked for Pixar and CORE Digital, weighs in on the intersection of 2D, 3D and CG.

New technologies straddle old technologies in their early phases but new technologies also put old ones in a new light. And visa versa.

Coke was just Coke until New Coke came along and made the old one classic. And a clock was just a clock until technology made us reconsider time as either digital or analog. Of course, its still just time being expressed in different ways. But think of how digital clocks make us newly aware of the properties of the analog ones digital clocks may be more accurate and easier to learn to read but analog gives us a more graphic picture of time a way to visualize a half hour, for example, that makes it more real.

So what can we learn from the beams reflecting off 2D, commercial CG-3D and new approaches to CG?

I continued my talk with Charlie Bonifacio about this subject and also sought an opinion from another angle while Bonifacio has deep roots in 2D classical Stephen Barnes trained in classical but has spent most of his career working in CG-3D at such studios as Pixar and CORE Digital.

We talked with the assumption that no one way is better than the other. In looking at everything in a new light, though, we have a chance to see new possibilities.

The first big question, of course, is the quality of the acting. How it is affected by new and old technologies and what role new and old technologies can play in making performance better?

For example, what about the issue of staging for clarity with voice, facial expression and body pose all communicating the same emotion? The alternative that Chris Landreth suggests treats the emotions expressed in voice, face and body in layers. Even within the body, Landreth talks about having different parts expressing different emotions with some parts being ahead of the others, rather than moving in emotional unison. Can any of this be applied to 2D or would this be, as some suggest, like comparing apples and oranges?

WB cartoons, graphic and flashy animation are comprised of poses while subtle animation, like Disney human beings move less from pose to pose. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs © Disney.

Bonifacio feels that the key distinction that needs to be made is one of context. Acting for cartoons has been pretty straightforward what a character expresses is what they feel, says Bonifacio. Disney has probably done some exploration into text and subtext- the words come out but they mean something different inside but its hard with drawings to communicate that sort of acting. Disney has done some work which is more subtle but the animation in the Warner Bros. shorts, for example, is really from the broad, cartoony school of acting. So the acting style relates to, more than anything, what genre youre working in.In terms of training the artist, regardless of genre or technique, I believe it is important for someone to first master the ability to say what they mean. There is a rigor in that which is a learning mirror. Once I am able to say what I mean clearly and succinctly, then perhaps I will be able to add the subtle nuances and layers of personality that make a more complex statement.

How does pose-to-pose animation fit into this?

When you get into WBs cartoony approach, says Bonifacio, It really is pose to pose. Graphic and flashy animation uses pose-to-pose more. Subtle animation, like Disney human beings, uses pose-to-pose less. Its the degree with which you hit poses that makes the difference. For example, in cartoon, youre hitting broad and strong.

Landreth also talked about the lack of poses in parts of Citizen Kane.

But there are sections of Snow White, particularly with the seven dwarves, where I defy you to find a pose. Look at Tytlas hand-washing sequence, for example. They were working straight ahead as well, says Bonifacio, And at some level Landreth, himself, is analyzing and selecting poses. There are fewer poses because its just two characters sitting at a table talking but when Ryan when gets mad and stands up and leans over the table thats a choice in pose that any good animator would do, classical or not.

Does this mean its the same process and the difference is only in the degree of subtlety?

Exactly. And you cant blame the pose to pose process for poor performance, continues Bonifacio, Its the animators who make too many choices, with too many poses. The quote I hear is a pose for every accent of dialogue but we know that doesnt work. You have to pick and phrase. Bad animators, like bad designers, choose every accent in the book a bad designer would fill this room with plaid, on everything a good designer will make choices and its those choices that make good design and good animation.

But why, then, do we see so much of that one pose for every accent out there?

Because people are badly trained. I dont think its because of the 12 principles.

They do talk about staging and unified fronts in The Illusion of Life and the necessity of making sure there is no ambiguity. But the importance of ambiguity is one of Landreths big points.

Theres ambiguity and then theres ambiguity. Chris Landreth strives for the kind that says this character is thinking two thoughts at once which creates internal conflict. Photo credit: Shira Avni.

But whats the difference between the chosen ambiguity that Chris achieved in Ryan and the unintentional ambiguity in motion capture films like Polar Express? asks Bonifacio.

Well, theres ambiguity and then theres ambiguity the kind that says, I dont know what the character is thinking, is uninteresting or off-putting. But ambiguity that says this character is thinking two thoughts at once is interesting because, as Landreth said, it creates internal conflict Im interested in you but Im scared of you; I want to say something but I dont want to say something.

Here Stephen Barnes chimes in with the concern that in the hands of a lesser talent than Landreth, the ambiguous approach could deteriorate into self-indulgence, reminiscent of the period when painters discovered video and you ended up with hours and hours of vague footage. By allowing for more subtlety in the animation, CG-3D opens the door to ambiguity but it takes discipline and clarity to make it work.

Remembering one of his first assignments, when he was making the shift from drawn 2D to CG-3D, Barnes says, I had animated a dog scrambling in fear and when the director looked at the shot in the graph editor he said it looked like a birds nest to analyze the paws were doing one thing and the ears another. But the director said that when he watched it, he couldnt take it apart; it had to be the way it was. It was a successful shot because I just naively thought, hey, I can move these separate body parts whenever I wish.

But can that be done consistently, particularly in a commercial setting?

It can all be handled in a fractured approach, says Barnes. But I think it still takes virtuosity to be able to rein it all in. The worry with vague ambiguity is that it would be undisciplined. And I think there is still a discipline in having all the elements seemingly, to paraphrase Stephen Leacock, chaotically running off in all directions.

In fact, it may take even more discipline. As with any art, what it seems to be on the surface can be different from what it is underneath. In this case, apparent chaos on the surface is actually a controlled process where the whole is greater than the parts. But what would a commercial CG-3D director have expected more typically to see in the graph editor?

The accepted norm is to have all the essential elements locked in, with what would be a keyframe, wherever there is determined to be a key pose, says Barnes, This becomes the equivalent of a single page of drawing. Eventually you get to polish your shot so that there is follow through, overlap etc.

But with my birds nest, it was fundamental that every element of the characters body had different keys at different times. It was exciting to animate because it was straight ahead stuff and I didnt record anything until the very end, so instead of being this analytical thing, it became a performance.

This is interesting because people talk about CG-3D being more mechanical. And, its thought, too reliant on the default settings of the computer.

Once youre up at the feature level, at least, says Barnes, A lot of things are done from scratch and there is the effort to be very gestural. Of course, if youre told you need to come up with 28 seconds of footage per week thats going to determine how much you rely on the computer to do the work, whereas, in Geris Game, for example, I produced 20 seconds in 16 weeks.

So the context of using the default settings is, perhaps, more like the CG equivalent of limited animation. But whats really striking in all this is the feeling of having achieved an animated performance, something that some consider harder to accomplish in CG-3D. And it was accomplished not by the current standard industry approach but more in a manner that supports what Landreth has discovered. So does this contradict the industry philosophy about applying classical principles to CG-3D?

Maybe this is not so much a contradiction, says Barnes, As an indication that the medium and our understanding of it simply hasnt matured yet. Nevertheless, how do both Bonifacio and Barnes feel about the levels of performance that have been achieved so far in industry CG-3D?

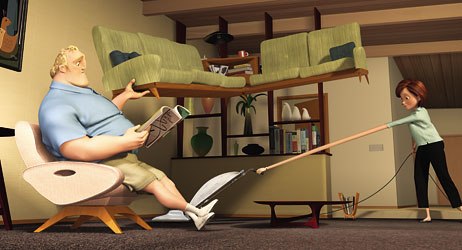

I think The Incredibles is successful in what they are trying to do, says Bonifacio, Though its dangerous to make across the board comparisons because every situation has a different context. At one point I did accept the believability of the characters and story in the first Shrek. But what I saw of the second one seemed unappealing, with live characters that dont look quite live only a little better than the feeling of the characters in Polar Express.In regard to The Incredibles, says Barnes, I understood that [Brad] Bird had an appreciation of what was possible in classical. And that he wanted to try to carry over as much of this as he could into CG-3D and so he was happy to ruffle feathers. I feel that he succeeded to a large extent. Certainly, it was a logical step forward, and a refinement of where Pixar were headed in terms of studio philosophy.

Charlie Bonifacio warns that 2D is in danger because everyones going CG-3D. In 10 years artists wont know how to do inbetweens or cleanup.

Perhaps we can say that with The Incredibles, Bird was definite about making a cartoon and with Ryan, Landreth deliberately crossed the line into surreal and both these clear concepts worked in creating performance but Shrek got stuck sitting on the fence sort of cartoon, sort of realistic but not quite enough of either.

So in terms of performance, in a period where everything is in flux, CG-3D does indeed seem to benefit particularly from clear context. But even with performances like those in The Incredibles, ones that advance the field, the question still remains whether the cartoon approach is the most suitable application of CG-3D.

Perhaps CG-3D is best suited for the situations that need extremely detailed subtleties so if youre going to have cartoony characters or stylized emotions like in The Incredibles, do we really need CG-3D? asks Barnes, Or could we go back to 2D? CG-3Ds still a stylistic choice but as far as necessity, its like you are using this finely sharp pencil to do something you could be doing with a charcoal pastel

I would love to think we could go back to 2D with its built in flexibility and total license. But can we, given the current CG-3D-centric climate?

2Ds in danger, says Bonifacio, Its going to lack resources for the next 10 years because everyones going CG-3D. So what do you do in 10 years with a generation of artists that dont do inbetweens or cleanup how so you find those people?

On the other hand, Pixars in a good position to come out with a 2D feature to rejuvenate the artform. Their approach to development is so unique; they could make a really interesting 2D film. Theres always speculation, though no confirmation.

The other issue that ties into this is the ongoing role of drawing, continues Bonifacio, I believe that by drawing, one can access something about the animation learning process in very unique and powerful ways. But even so, the jury is still out for me. If drawing is just a tool, as the computer is just a tool, then perhaps either is expendable. We rarely use the quill pen anymore; do we still really need to draw?

With The Incredibles, Brad Bird definitely made a cartoon but the question still remains whether that approach is the most suitable application of CG-3D. © 2004 Disney Enterprises Inc./Pixar Animation Studios. All rights reserved.

But often in these transition periods the older technology emerges with a new role.

I feel that when we look back on this era it will be compared to the painting versus photography issue, says Barnes, And while some people say its either/or, Id love to think that there will still be a place for 2D. As someone who went into it not for the specific technique but because I loved the idea of bringing things to life, I would vote for not throwing anything out and instead think that there is a master plan of how everything relates.

Perhaps the model, then, should be one of cross-reference: 2D and CG-3D influencing each other. If the 2D classical principles can directly influence the CG-3D cartoon approach, then perhaps the other extreme of Landreths ambiguity could influence the approach to performance in 2D and commercial CG-3D. Right now, we have two extremes in performance with Ryan on one hand and the unified front on the other. How about something inbetween broader than Landreths multi-level approach but perhaps showing two or three levels of thought/feeling? This would still extend the acting range into something more subtle and real, an approach that could work even in industry applications of 2D and CG-3D.

Of course, though, 2D still faces the obstacle of a pencil which can only be made so sharp its not the 2Dness that restricts it but a technical limitation of its primary tool. It cant, as Barnes points out, show a slight shift of an eyebrow the way Landreth or even Pixar in Geris Game could.

I see 2D, not so much as dying as going through a fallow period, says Barnes, There may be a period of quietness while everyone is rushing after CG-3D but then there would be a point of readiness in the marketplace for re-exploring all the possibilities. In that time, 2D would not just be pencil and paper. In the next few years, I foresee all sorts of interfaces and my thought is that 2D could be saved by the very CG technology which is replacing it now.

It would still be truly 2D but with styluses on tablets and perhaps digital paper that could still be flipped. And if 2D previously couldnt get subtleties in an eyebrow expression, now we could zoom in on the drawing, make a subtle move and then zoom back out again. So now, all of a sudden, youd be drawing with that sharper pencil.

Shrek got stuck sitting on the fence sort of cartoon, sort of realistic, but not quite enough of either. Courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures.

And then you could choose 2D or CG-3D, each for its own best properties, depending on the project.

Or it will be a melding of the best of both, says Barnes, Capitalizing on the strengths of each.

So maybe the most interesting future scenario for animation lies in the willingness to consider the possibility of new contexts that allow new reference points. We still may be dealing with apples and oranges but what happens if we do a little slice and dice? Fruit salad would be a pretty tasty outcome, one that could mean more creative possibilities for everyone.

Well, this has been quite an unexpected ride. What started, in my mind anyway, as a single article on realism in animation just kept growing, with each article opening new facets of a subject well worth exploring. Next time, though, well likely come at the idea of making things real from a distinctly different angle. See you then.

Ellen Besen studied animation at Sheridan in the early 1970s. Since then she has directed award-winning films both independently and for the NFB, worked as a film programmer and journalist, taught storytelling and animation filmmaking at Sheridan and given story workshops at many institutions and festivals, including the Ottawa International Animation Festival. She is the director of The Zachary Schwartz Institute for Animation Filmmaking, an online school that specializes in storytelling and writing for animation.