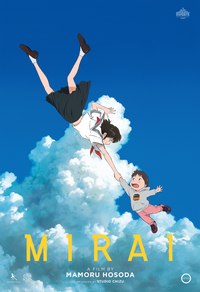

The acclaimed director of ‘Wolf Children’ and ‘The Boy and the Beast’ paints an intimate portrait of a young boy’s vivid imagination and how it helps him accept the arrival of his baby sister in one of the last Japanese animated features to employ hand-drawn animation.

Since its debut as an official selection at Cannes Directors’ Fortnight, acclaimed Japanese director Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai has steadily generated Oscar buzz for U.S. distributor GKIDS. Considered the epic capstone of Hosoda’s career, Mirai blends traditional hand-drawn artistry with CG animation to tell a story of love passed down through generations. The film was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Animated Motion Picture, and received two Annie Award nominations -- for Best Animated Independent Feature and Outstanding Achievement for Writing in an Animated Feature Production -- and is one of five nominees for Best Animated Feature at the upcoming Academy Awards.

In Mirai, which was produced by Japan’s Studio Chizu, the studio behind Hosada’s two previous films, Wolf Children and The Boy and the Beast, four-year-old Kun’s world is turned upside-down with the arrival of his new baby sister Mirai (which means “future”). Kun struggles to maintain what he views as his rightful place in the family as the center of attention, but is no match for the newborn, until one day he storms off into the garden, where he meets a cast of strange characters from the past, present and future -- including a teenaged Mirai. Gloriously bringing the toddler’s vivid imagination to life, Mirai leaps off the screen and into our hearts.

Aside from its heartwarming message, what makes Mirai particularly special is that it might very well be one of the last Japanese animated features to employ classic hand-drawn animation. “For this movie, the background was done with paint-on-paper. One might think, ‘Isn’t that normal for anime?’ but it’s actually a dying art. Everyone is moving on to digitalizing or doing backgrounds on a computer, so this film, and probably Miyazaki’s next film, will be the last ones to have backgrounds with paint-on-paper style. It’s really too bad that it’s going to be gone, but that’s just the way life is. Styles and techniques are always evolving and we have to move on,” Hosoda confirms via an interpreter during a recent visit to Los Angeles.

Twenty artists in all contributed to the backgrounds in Mirai. “These 20 artists are literally the last people in the Japanese animation world who would use this style of paint-on-paper -- because after they had finished his film, they are probably working on Miyazaki’s last film -- after that, no one is going to ask them to do paint-on-paper, so they’re moving on to digital,” he continues. “It’s really sad.”

While Hosoda is prepared to move on and adopt CG technologies, he also plans to continue to try to incorporate hand-drawn elements into his future work. He describes the current state of the animation industry in Japan “a turning point,” and says he’s already thinking about his next film. “I’m really thinking about how it will it be different, will the characters be all hand-drawn, or will the characters be a mix of hand-drawn and CG?” he questions. “It’s really going to depend on what the overall story is, and how we will try to tell that story. I’m very sad about hand-drawn animation not being utilized as much, but, I’m still thinking about it.”

Although it might not be immediately apparent, Mirai, Hosoda says, employs the largest amount of CG of all his films to date. That’s because the director and the artists at Studio Chizu have been trying to re-create a hand-drawn aesthetic using computer graphics. “There are actually many parts where you can’t really tell that it’s CG,” he notes. “The CG elements are hidden. We did that because we’re trying to experiment with what we can do utilizing CG and hand-drawn animation, so there’s parts that are not CG-like and parts that are CG-like, and you just can’t tell.”

Certain scenes in Mirai, such as a fantasy sequence in a crowded train station, look markedly different from the everyday world of the film. “That sequence is really the part where Kun has lost his identity,” Hosoda explains. “He’s lost who he is. That scene, the clock-man, his role is to ask Kun, ‘Who are you?’ I really wanted that character to have authority -- he had to have the right to ask that question of Kun’s identity, so it really had to be someone who was specially designed, not like a normal person, so we used a cut-out picture for him and animated him with CG, so his eyes are cut out and they look a little hollow, and he has all these sharp edges. I wanted to make the whole scene stand out because it really is about the identity question, but also because I, myself, have identity issues that I carry within myself,” he shares.

While characters such as the train station attendant are designed with whimsical appeal, Hosoda sought a more familiar and credible visual style for the human characters in Mirai. “I really wanted the human characters to be realistic, but that really depends on who draws them,” he says. The director hired a husband-and-wife duo -- Emmy Award-winning Hiroyuki Aoyama and Ayako Hata, both of whom collaborated with Hosoda on The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, Summer Wars, Wolf Children, and The Boy and The Beast -- for the character designs and animation supervision. “Because they were really a couple, they were able to depict a realistic family dynamic,” he notes. “They’re really good.”

Capturing Kun’s expressions was one of the most challenging parts of the film to animate, according to Hosoda. “When animators are like, ‘Oh, yes, I’m going to draw a kid,’ they think of what they think a child is like. I didn’t want that, I wanted a realistic depiction of children, so I brought my son to the studio and had something like maybe 20 animators surround him. Not only to sketch him -- they held him, felt the softness of his skin, and the thinness of his hair,” Hosoda recounts. “He hated it, but because of the extra step we took to re-learn what child is like, we were able to really depict what a children is like in the animation.”

Mirai contains several fantasy sequences but is still very much rooted in everyday life. “Kids see the world in a fantastical way,” Hosoda observes. “Every day brings something new and fantastical, so, all the things Kun imagines, that’s just how kids see the world. As adults, we think, ‘Oh, well, we can’t talk to dogs,’ but then maybe, children, the way they see it, they are able to talk to dogs; or when they can’t ride a bicycle, but then suddenly they can, maybe, somehow in their life, it’s like someone taught them. Adults don’t really see it, but kids can because everything is new and they don’t even question it, they just accept it.”

For Hosoda, Mirai represents his most personal film. “In this day and age, raising children is so difficult,” he chuckles wryly. “Before I had children, I thought having children was a hassle -- they cost so much money, you don’t get any time, you don’t get any sleep -- that’s what I had thought. That’s actually true, yes, it is a big hassle and does cost a lot of money, but to spend time with children, it just brings so much happiness that none of all the hassle and time matter. I really wanted to depict that in this film, so I based it on my own children.”

While many of Hosoda’s previous films have featured high-flying action and fantasy, Mirai is firmly rooted in the domestic world. “When you have a film with children in it, people think it has to be some kind of holiday movie, or it has to be some action movie where there’s like a hero, and then the boy goes on an adventure, and there’s an antagonist, and he defeats him. Unless you have all those elements, people tend to think it won’t be enticing to audiences,” Hosoda comments. “I wanted to show that, no, other films can be enticing. Life with children, everyday life, there is happiness hiding in those everyday life moments, and I really wanted to depict that,” he says.

What ties Mirai thematically with Hosoda’s previous films is the idea of family. “They’re all connected,” he insists, noting that he always gets his inspiration from the things and people closest to him. “The important thing about the theme is how adults teach kids and young people how to live in society -- how do they pass the baton?” he asks.

“Really, the sad thing about modern society is that it’s really become world for adults world; adults are the most important, but that’s not true,” Hosoda comments. “Young people tend to be tossed aside; they tend to be seen as secondary people, but that’s not true. In order to build a new society, kids and young adults are important and adults have the responsibility of teaching them so that they can build the new society.”