Philippe Moins reflects on the life and early animation contributions of RenLaloux. The French master died of a heart attack in Angoule, France, on March 14, 2004.

René Laloux 1929-2004. © Dreamland éditeur, 1996.

With his little saltnpepper moustache, spectacles and paunchy physique, René Laloux looked like the archetypal Frenchman. Yet this debonair appearance, who passed away March 14, 2004, belied one of French animations most highly original personalities, one who at times was anti-authoritarian, and often displayed a tendency to contrariness. In retrospect, Laloux was in fact a pioneer, who on several occasions got it right -- but was too far ahead of his time.

Born in 1929, Laloux wanted to become a painter. Biographers note that in the mid-50s he took on several different jobs to get by; he was subsequently employed by the Cour-Cheverny psychiatric clinic, run by the doctor Jean Oury, where he put on puppet shows with his patients. In 1960, his first short film, Les dents du singe, written and drawn by the clinics patients, drew attention to this thirty-something with progressive ideas and unusual therapeutic methods. This rather striking piece of work immediately made a mark, winning the Prix Emile Cohl.

In 1964, he started directing professionally, making another short with Roland Topor, Les temps morts, followed in 1965 by his most well known short film, Les escargots. It was quite natural for Laloux the puppeteer to turn to paper cutouts for these three films; a choice dictated as much by taste as by necessity (puppets and cutouts being directly animated under the camera). Les temps morts is an anti-militarist film, shot through with Topors black humor. Its crosshatched graphic style, which looks rather like etching, became Laloux trademark signature up until La planète sauvage.

Les escargots presents us with an everyday fantasy world: a gardener, growing lettuces, unwittingly sets off a series of catastrophes. The film won numerous international prizes, including the Grand Prix at the Mamaïa Festival (Romania) and the Special Jury Prize at the Cracow Festival. Whereas Laloux was still an unkown, Topor had already made something of a name for himself: an engraver, illustrator, screenwriter, he also wrote novels and short stories. By the late 60s his artistic work had achieved an international reputation, and his work was exhibited in London, New York and Chicago. Laloux himself continued to paint, but without ever really making his name in this field.

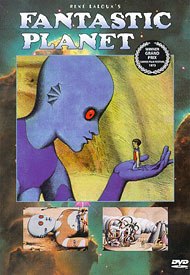

His collaboration with Topor led to the making of the animated feature, La planète sauvage. Laloux, a science fiction fan, persuaded Topor to work on an adaptation of the work of Stefan Wul, one of the best French writers in the genre. A dental surgeon, Wul had written a dozen sci-fi novels in his spare time, published in the highly popular Anticipation series in the mid 50s by Fleuve Noir, which also specialized in detective and espionage thrillers. The covers, designed by the illustrator Brantonne, were not dissimilar to American publications such as Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories of the preceding generation. But content-wise, they could not have been more different.

Unlike most Anglo-American sci-fi, Wuls were informed by a poetic vision; he imagined worlds and civilizations with none of the usual technological, space and mechanical paraphernalia that was then the norm in classic sci-fi. It must have been this near-naif, surrealist aspect of his work that intrigued Laloux and Topor. La planète sauvage is based on Wuls novel Oms en série (1957) The story unfolds on a planet where very tall blue androids enjoy a highly civilised life, but treat other, much smaller beings with a condescending gentleness, as if they were pets. Some of the latter live in the wild and are hunted by the former. Once caught and tamed, the storys protagonist is caught between his origins and his status as a domesticated pet, which inevitably leads to conflict with his masters.

Somewhat Swiftian, the story has some affinities with Planet of the Apes, the French novel by Pierre Boule which was adapted for the cinema around about the same time. However, the fact that it was an animated film with a lyrical strain made it sufficiently different and its originality lay in the fact that instead of describing brute coercion it creates an ambiance of gentle slavery; in all, a highly premonitory satire.

The English-language version of La planète sauvage featured actor Barry Bostwick.

At that time, producing an animated feature in France was simply unthinkable. Yet Laloux did it, working with enlightened producers such Anatole Dauman, Simon Damiani and René Valio Caviglione, none of whom had any prior experience with animation (Dauman had been closely involved with the New Wave). Given how difficult it was to work in France, they planned it as a co-production with Czechoslovakia. Their plans, developed at the very moment of regime liberalization, hit a major roadblock however in the shape of the brutal events of August 1968, when Russian tanks rolled in to crush Prague. This explains, in part, why the films production process took much longer than anticipated: it was made between 1969 and 1973.

The Czech authorities, disenchanted with this co-production which, whilst bringing in foreign currency, bore no relation to socialist realism, were finally obliged to look pleased when the film took the Cannes Special Jury Prize in 1973. The choice of Prague was obviously justified on economic grounds: at that time there was certainly no studio in France that could have taken on a production of this scale, even less so on such a small budget. But choosing Prague also had another rationale. The film needed to be made using the technique of paper cutouts that were both hand-crafted yet quite sophisticated and the Prague artists, who had broken with under-the-camera techniques, were at that time particularly able to take on this challenge.

Due credit should be given to the work of the artists and animators at the Jiri Trnka studio; without their mastery of a technique that was somewhat neglected in the world of 2D drawn animation in western Europe, the film would never have looked as good as it does. The films title sequence credits art directors Joseph Kabrt (characters) and Joseph Vania (backgrounds), as well as the DoPs Lubomir Rejthor and Boris Baromykin. The latter is still working, and was recently involved on a Jan Svankmajer project.

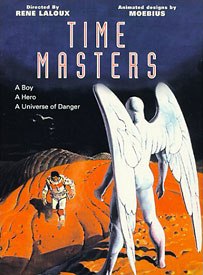

Laloux joined forces with graphic artist Moebius to create Les maîtres du temps.

Part of the films strangeness comes from this animation style which seems to emerge from nowhere, bringing giving life to drawings that are both academic and somehow out of time. It is likely that at that time, paper cutouts were the best way to maintain the line and the hatching so characteristic of Topors work. The deliberate asceticism of the backgrounds (large bare spaces studded with the characters graceful silhouettes) and the limitations of the characters movements, inherent to this technique, give the whole a special ambiance which has rarely been seen since.

Although he was preceded by the American Gene Deitch, who had been working with the Czechs since 1959, Laloux was, in his own way, a pioneer in terms of collaborating with near and far Eastern studios, which he did again for his two other feature films. Les maîtres du temps was made, in part, in Hungary before the fall of the Berlin wall, and Gandahar was contracted out to the S.E.K. studios in Pyong Yang, North Korea.

Yet despite the success of The Fantastic Planet, particularly in terms of critical response, Laloux subsequently experienced a long fallow period before he was able to make his second feature, partly due to the ailing state of the French industry at the time. Les maîtres du temps (1982) was also based on a novel by Stefan Wul, Lorphelin de Perdide. The film exploits the temporal paradox beloved of French sci-fi, alternating scenes featuring a globetrotting old man travelling through space with others in which we follow a young boy on a strange planet. Only the ending reveals who they are in reality.

Moebius took on Topors previous role as art director and graphic designer, which made the visual style more commercial, somewhat similar to the comic book style the French artist had initiated some years earlier with his comic strip Arzach. The scenes set in space disconcerted critics with their similarity to the mangas that had just begun to appear on French TV. The scenes on the planet are more reminiscent of the world of The Fantastic Planet, with its fantasmagoric imagination: fauna and strange vegetation, invasion by giant hornets, etc. Although the animation is uneven, a number of sequences are extremely impressive, and the Pannonia studios in Budapest made most of these.

With this film Laloux tried to bridge the two worlds of animation and the new French comic books, a laudable endeavour, but one that proved more difficult than anticipated. Since then, other filmmakers have tried to transpose the worlds of Moebius and Philippe Druillet to cinema; yet in retrospect the only film that stands up is Les maîtres du temps whose oddness, lighter in tone than in La planète sauvage remains however its main credentials.

The film achieved no more than critical success, but definitively established Lalouxs uniqueness: René Laloux... alone represents not only the whole of French science-fiction animation, but even now the only kind of French cinemas science-fiction (Gérard Klein). This statement obviously predated the arrival of Enki Bilal and Luc Besson on the French cinema scene some years later. René Laloux made his third feature in1986-87; by which time he was approaching 60, and the films development process was very complicated since this time he opted to move all the animation work to Pyong Yang in North Korea.

Gandahar (1986-1987) was an adaptation of Jean Pierre Andrevons novel, Les hommes machine contre Gandhar. A paradisiacal world is threatened by a mysterious enemy, who turns out to be metamorph, a creature made of pure thought; the only way to counter its power is to manipulate time itself... a story which can obviously be seen as relating to the earlier work. Until then, lack of money had been compensated for, indeed sublimated by, a formal and storytelling ingenuity; here this no longer applies and the film lacks energy. Laloux seemed to be repeating himself, with less inspiration and more sweat: the traditional technique of painted cels once again shows its limitations, as it does whenever too much is demanded of it.

Perhaps the same film, made 10 years later using digital techniques would have been more satisfying for fans of that form of science fiction that is more kitsch than inspired; unable to count on Moebius collaboration, Laloux turned to another sci-fi illustrator, the Frenchman Philippe Caza. Laloux made a short film with the same crew in Pyong Yang (Comment Wang Fo fut sauvé, 1987, adapted from a short story by Marguerite Yourcenar) and was involved in various TV series projects and scripts, before devoting himself entirely to teaching in Angoulême.

Before he retired in 1999, he produced a highly personal take on the history of animation in the book Ces dessins qui bougent (Dreamland 1996). He also initiated les enfants de la pluie, an animated feature adapted from the French sci-fi writer Serge Brussolo, but in the end it was Philippe Leclercq, a former colleague, who directed the film, in 2002, on the basis of drawings by Philippe Caza.

In the early 80s, Laloux had discovered Japanese animation which was then undergoing a real boom. He had a deep admiration for Hayao Miyazaki and maintained IsaoTakahatas Tombstone of the Fireflies to be a masterpiece, a judgement that has since been widely echoed. But at that time, in the early 90s, Laloux was one of only a small circle of admirers encouraging the introduction of films from the Ghibli studios in France. Which is greatly to his credit. Whether this admiration was reciprocated, we do not know, but in any case it would be fascinating to make a comparative analysis of the way time and atmosphere are handled by Miyazaki and Laloux... but that would be another article altogether.

Over the course of his career, Laloux worked with some of the most eminent representatives of French language science fiction, both in terms of literature and visual art. He has the audacity to believe in the potential of people who had hitherto been ignored by French cinema; and in doing so, he undoubtedly contributed to giving these writers works a second life. It is well known that Moebius went on to work on feature films, in the U.S. as well as in Japan. Laloux also made a huge gamble on using the artistic talents of countries in the east, without being coy about it.

Since the release of La planète sauvage, many French animators have dreamed of moving into feature films like him. Such dreams have taken a whole generation to become a reality.

Philippe Moins is a writer and teacher in Belgium, and also the co-director of Anima 2003.