Fred Patten likes what he sees in an impressive new book chronicling the history of CGI in film.

The CG Story: Computer-Generated Animation and Special Effects, by Christopher Finch. Illustrated.

NYC, The Monacelli Press, December 2013, hardcover $75.00 (288 pages).

I am very impressed.

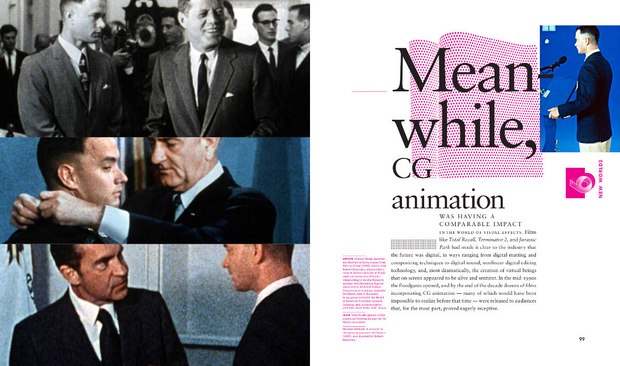

This book is a visual standout. It is in full color. It is over a foot tall and almost a foot wide – 13.3” tall and 11.5” wide – and weighs 5.5 pounds. It is illustrated on practically every double-page spread. The reproductions of computer-generated images go back to 1839; a woven silk portrait by Michel-Marie Carquillat of Joseph Marie Jacquard, the inventor of the Jacquard loom, a loom that could be programmed by hand-punched cards to repeat a woven design. Jacquard’s portrait on a silk sheet was “laboriously orchestrated by means of twenty-four thousand hand-punched cards. It can be thought of as the first complex image to be produced by means of programmed computation, and as such it is a direct ancestor of all computer-generated imagery.” (p. 23) Since it was mechanized, Carquillat could produce not just one but many identical copies.

Finch’s The CG Story comes just eight months after Tom Sito’s Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation, but the two are very different. Where Sito’s book is a history of computer animation placing the emphasis on the computers, the inventors who created the advances in computer graphics, and the names of each technological breakthrough, Finch’s emphasizes the CG as it applies to popular films. In his prologue, Finch cites the popular 1940s-‘50s movie actor Victor Mature, who never acted when he could get a stand-in or a stunt double to do it. “He once stated that his ambition was to star in a movie in which he never actually appeared.” (p. 13) Finch points out that with CG, Mature could do this today. (In 1983, writer-artist Howard Chaykin introduced American Flagg!, a fifty-issue s-f comic-book set in 2031, featuring the adventures of Reuben Flagg, an ex-TV adventure-actor who was fired after his studio got enough footage of him in its computer-camera that it could create artificial imagery of him for all future episodes.)

Is there a difference between CG and CGI? Most people would say no, but Finch says yes. “The tool that would have made this possible is computer-generated imagery, “CGI”, usually referred to as just “CG” when applied to computer-generated animation.” (pg. 13). But everyone that I know says CGI when referring to computer-generated animation.

Whichever is used, Finch makes a sharp distinction between computer-generated animated films like DreamWorks Animation’s Shrek features, and VFX-heavy “live-action” features like the 2013 “realistic” s-f movie Gravity, which some argue should be called a computer-animated film for the amount of computer imagery in it.

The opening chapters of The CG Story are very similar to Sito’s Moving Innovation, as Finch tells what the historically important computer innovations were, who made them, and when they were made. But Finch quickly shifts his emphasis to these computer innovations’ use by the movie studios; particularly how they led to new computer-animation studios. In fact, Finch devotes so much space telling who were the key personnel at Pixar Animation Studios and DreamWorks/DreamWorks Animation, how those studios started, and what their first features were, that the book is practically the history of those studios alone.

The CG Story tells in alternating chapters the chronological development of CG animation – Pixar’s 1980s shorts, Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, Dreamworks’ Antz, Toy Story 2, Shrek, the appearance of Pacific Data Images’ and Blue Sky Studios’ films; alternating with the first movies to employ VFX instead of non-computer special effects, the Terminator movies, Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean movies, the Harry Potter movies, the Chronicles of Narnia features, and so on. The studios started to specialize in computerized VFX are named: Industrial Light & Magic, Digital Domain, New Zealand’s Weta Digital, and many others. The different CG techniques and terms are enumerated; digitally-generated special effects, CG shots, motion-control, 3-D CG effects, generated-in-the-computer imagery, digital compositing, motion-capture. The CG pioneers are named; not just the technicians, but the first directors and producers to champion CG; Ridley Scott, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas in the 1970s, Ed Catmull and John Lasseter in the 1980s, Jeffrey Katzenberg and James Cameron in the 1990s. Finch points out that older movies required major studios to invent or improve filmmaking techniques, but, “The fact that CG animation creates its own sound stages, its own backlots, its own locations within the computer means that CG studios can spring up anywhere, and they have.” (p. 18) Australia’s Animal Logic studio in Sydney, India’s Prana Studios in Mumbai, Hong Kong’s Imagi Animation Studios.

The CG Story seems to include everything, down to the lone CG features of brand-new studios and the odd CG trials of studios not usually associated with CG. The book is current up to the end of 2012, with District 9, The Life of Pi, Rise of the Guardians, and Wreck-It Ralph.

One special touch about The CG Story that I like is that parenthetical asides are not only put within parentheses, they are set off with a different typeface. I have never seen this before, but it’s very effective.

For a detailed history of every technological advance in computer graphics, get Tom Sito’s Moving Innovation. For a lavishly-illustrated detailed history of every CG advance in the cinematic entertainment industry, plus the histories of Pixar Animation Studios and DreamWorks, you have to have Christopher Finch’s The CG Story.

--

Fred Patten has been a fan of animation since the first theatrical rerelease of Pinocchio (1945). He co-founded the first American fan club for Japanese anime in 1977, and was awarded the Comic-Con International's Inkpot Award in 1980 for introducing anime to American fandom. He began writing about anime for Animation World Magazine since its #5, August 1996. A major stroke in 2005 sidelined him for several years, but now he is back. He can be reached at fredpatten@earthlink.net(link sends e-mail).