Bill Desowitz gets an early peek at the new previsualization techniques developed by production designer Alex McDowell for DreamWorks' upcoming Bee Movie.

Production designer Alex McDowell, who has been at the forefront of previs innovation in live action, has helped DreamWorks Animation become more efficient as a result of his tenure on Bee Movie (opening Nov. 2). And now that he has gotten his first taste of 3D animation, McDowell looks forward returning again. He spoke to VFXWorld by phone in Vancouver, where hes working on Warner Bros. Watchmen with director Zack Snyder.

"In many ways, doing Charlie and the Chocolate Factory pushed me toward working in animation because it was that hybrid, McDowell reflects. I was sitting in the visual effects houses alongside modelers and surfacers and lighters and designing almost live in 3D, which was really exciting. And also giving me a measure of control over those things that I wouldnt have normally for a couple of reasons: First, you cant always create the kinds of surfaces and materials that you can imagine, and you also have so much more scope in the virtual world to design exactly what it needs to be -- physics alone deter some of the design that we envision. So after going through that experience really closely, interfacing with visual effects, the Bee Movie experience was a leap into full virtuality.

However, when McDowell was brought in two years into the development process, he ran into a formidable obstacle: In animation, previs is called rough layout and begins way too late to serve McDowells design needs, as he utilizes them in live action. The problem with layout, I think, from a design point of view is two-fold: One is that the proprietary [Emo] software of DreamWorks doesnt allow you to manipulate the environment once it goes into rough layout, at least not easily. Thats a practical problem, which means if I waited till rough layout and wanted to make changes, which was the standard pre-Bee Movie, Id have had to pull the model out of layout, back into modeling, make the change, convert it back into Emo and then layout would redo the camera and action to align with the change in environment.

The other problem by the nature of the traditional pipeline is that you have to finish design before it goes to layout. And, for me, design is as much about what the camera does in the space as it is about driving the action. And for the past few years, thats been whats great for me about working in live action. Because we are now able to place the camera and actors in a virtual environment, which means we can be more intuitive about the design, the director has much more early control and we can talk collaboratively about the real function of what the environmental battle is going to be for the action and then design specifically to that. And the traditional animation layout process doesnt really allow that. You have to make a lot decisions about environment and then you place characters, which very often havent been developed fully until they get to rough layout, and the camera has never seen character in environment until they get to layout. And so -- to use a ridiculous example -- if theres a wall or even a piece of furniture thats sitting in the way of the directors blocking, you may not discover that until you are in the middle of (very costly) production."

So first McDowell had to make his case: When we first started talking about it, there was a sense that there was no difference between previs and rough layout or that the two were in conflict. If you did previs too early, youd be treading the same ground as rough layout, which youd have to tread again later. And so what we first had to do was show how previs is proven to work in live action as a planning, design and layout tool.

replace_caption_bee02_BeeMovie-PreVis-Kitchen-may.gif

While we were making our case for previs officially, we were already building cameras into environments to test the design. For Bee Movie I had to design some sets from scratch in a very short period of time, so in some ways it was the liberating factor because I had to say that the only way we could make the schedule would be to design and make all our key decisions in 3D. We didnt have time to do concept art, or go through the 2D development process, which has been common in animation up to now, but rather to design even the simple sets in 3D and place cameras and work out the blocking and test them with the storyboards and story reels and then move those models straight into final modeling.

In order to do that, one of the political boundaries that we broke down was to import some modelers from the modeling department into the art department and start to blur the divide between design and modeling. That way we were able to design in 3D in Maya, get it up to a certain point and pass it over to modeling to finish, rather than the traditional linear design process of designing everything in 2D and then have the modelers interpret the design and then come back and change it, and repeat. So for the designer, because I can then look at the design in the camera, we had a lot of rough characters or, in fact, quite fully developed characters because its so late, that we could place in the environment, and so we had scale reference and we had all of the components that we needed.

McDowell brought in previs specialist and long-time collaborator Ron Frankel to help with the transition. Frankel gave a talk to the DreamWorks Animation group and used a lot of live-action examples from films hed worked on, including Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Constantine and World Trade Center. Because of the initial confusion, they had some difficulty at first finding people to assign to previs. So Ron put a small team together, adding a couple of people from [his company] Proof at DreamWorks working as a previs unit with one DreamWorks layout artist. There was a really good cross-pollination. DreamWorks became very excited about working in previs too.

Political boundaries on Bee Movie broke down when some modelers were imported into the art department and the line blurred between design and modeling.

So we moved really quickly. An advantage of DreamWorks during the early stage is that most of the great artists in the Bee Movie art department were adept in both 2D paint and 3D Maya. [Maya is the tool of choice up to modeling and then it goes into Emo.] That means that in visual development the artists are largely bouncing between Photoshop and Maya. So as previs started coming in, we exported jpgs out of the 3D environment from the camera view, as we do in live action, and used those as the underpinning of the Photoshop concept art. You can discover a lot of problems in 3D and in pre-production have the time to fix them. When you start pipeline, youre into shooting costs, so its a lot harder to slow it down. The big push for me was to say, whether you call it rough layout or previs, you allow it to start at the beginning of the design process, so you will be able to think about action and blocking and lighting and character in development rather than during the shoot. And, of course, you can explore with the director all the creative decisions in the same 3D space that you will be shooting.

To further avoid any of the semantic confusion between previs and rough layout, McDowell re-labeled previs design visualization, or d-vis, for animation. Rather than having story and visual development as two distinct strands, which is a year of separation before they come together in production, the d-vis that McDowell introduced brought them closer together. Its as if, in live-action terms, one never put the camera, actors and environment together until the start of shooting. Theres obviously such a strong possibility that something is not going to jell between those two components. As much as story drives design, there are constant examples in my experience of design having a profound effect on story, but this only happens effectively if they are woven together from the beginning. The previs mindset is essential now because its such an appropriate forum for all departments to discuss a film. This virtual production space accurately forecasts the structure of the final film, especially in 3D animation, or digital film."

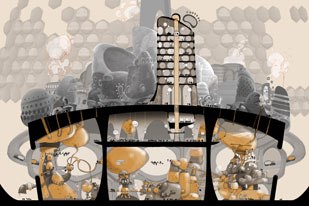

The Hive world of Bee Movie is a little town with a Queens tower in the middle, all of which sits on top of the giant factory known as the Honex. So the whole hive is built upon and feeds off of this Honex Corp. like a traditional little British mill town, which, according to McDowell, is a Charlie and the Chocolate Factory reference.

With d-vis, action, blocking, lighting and character can be dealt with in development rather than during the shoot. Also directors can explore creative decisions in the same 3D space in which they will be shooting.

The directors were always in an interesting position because Jerry Seinfeld is a very strong creative leader. Simon J. Smith comes from visual effects, and being a head of layout at PDI. Steve Hickner had directed Prince of Egypt. So Steve had great story background and knew DreamWorks inside out, and Simon was really good with camera -- maybe stronger than any previous director at DreamWorks. Simon and I had a great collaboration, although as a head of layout his instincts initially were to make a lot of decisions at the layout stage, and so he was slightly resistant to the idea of previs early on. I think once we got it rolling and he saw that he could sit with previs artists and really do layout and make very controlled camera and blocking decisions, it was good for all of us.

On some of the big sets it was really complicated. In Central Park, you really travel quite a large distance following a small bee and very three-dimensional, going way up into the clouds and swooping down and going through all sorts of objects. At some point, you have to decide what youre going to build and the terrain is completely determined by what the flight of the bee is going to be. It wouldve been really tough to do that sequence without previs in place. So the terrain design was going on side-by-side with previs, and every time we updated previs, that day it would go into modeling, so not only was the environment sympathetic to camera and action, but also we were able to make the environment more dramatic because we knew what the camera needed to do. We could add a cliff here or an obstacle there in a way that the storyboards would not have indicated.

The Honex, the giant factory in the bee world, is mostly comprised of animated machines. Mike Isaak created the 2D drawings,which showed the machines doing crazy things with honey.

One of the great things about working in animation is your resources. The Honex, the factory component of the bee world, was mostly animated machines: the humor, the action and the scale of the space were driven by the kinds of machines and their function. Its great fun to design these and we had incredibly inventive artists like Mike Isaak, who did beautiful 2D drawings, very funny schematic drawings of machines that did crazy things with honey. But at some point, very quickly, in order to elaborate on that design and see what that machine could do, we were able to put a team together for a couple of weeks that consisted of half previs and half visual development artists that just hammered together at this animated sequence that was all design driven. This was designed to show Jerry Seinfeld and the directors what you could do with the machines in space, and it was fun working in animation because it was really fast and very clear. Again, it opened up the need for more focus on animation in design development because you want to make the space really active.

McDowell concludes that working in animation enhances his ability to have a dialog with the whole arc of production. On Watchmen, for example, there are intense conversations about a single shot -- there are pieces of the shot that are visual effects and pieces that are live action, and you end up working out the logistics and parceling out the work, of course. But in terms of a creative conversation, you dont need to know how each part is going to be done in order to have the discussion. You need to know what the creative intent is and then you break it down, collaboratively. So the more I know about the film space, the more I can design to its full potential, and the more creative and exciting are the possibilities.

Bill Desowitz is editor of VFXWorld.