Find out how to get started on your animated short in our latest excerpt from the Inspired series.

All images from Inspired 3D Character Animation by Kyle Clark, series edited by Kyle Clark and Michael Ford. Reprinted with permission.

The last few chapters of this text examine the production of a series of animated shots. Its an opportunity to combine the fundamentals and processes discussed throughout this book. Hopefully this will give you valuable insight on how to approach your own work and develop your own set of production processes.

I have developed a very short story and created a minimal set with one character. This basic framework should be sufficient to demonstrate the production of shot from beginning to end.

Along the way, I will implement many of the tips, tricks and techniques specific to character animation, as well as recap some issues discussed in Chapter 5: Approaches to Animation. In addition, I will discuss topics associated with refining the finished animation.

Storyboards

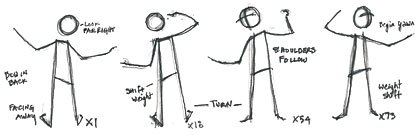

A storyboard is a two-dimensional drawing created to define the actions of a shot or scene (see Figure 1). These drawings are generally produced by story artists and are used to convert the written words of the script into a visual format providing a detailed description of the actions and emotions associated with the story.

The storyboards provide valuable insight into the scripts intentions regarding action, emotion, and orientation. Multiple drawings are usually generated for each scene. This series of images provides the basic beats for the animator. Timings are generally associated with each drawing to supply the animator with a good idea of how long the character needs to perform specific actions.

Drawings generated for this project include 10 shots with 20 storyboards. These illustrations provide insight into the various beat s of the story and suggest certain personality traits that might work in the scene. You will definitely want to use these images as reference.

![[Figure 2] Looking tired is an important expression in this short story. [Figure 2] Looking tired is an important expression in this short story.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2121-i3d02fig02.jpg?itok=D6ckWuNe)

[Figure 2] Looking tired is an important expression in this short story.

As shown in Figure 2, the story artist has captured a distinct moment in the story with an expression that is characteristic of the attitude and emotion of the main character. The complete set of drawings is shown in Figure 3. Notice the beats the story artist chose to illustrate.

These drawings not only provide inspiration, they create the framework within which you must work. Animators rely on these drawings to define action, paint an emotional picture, and keep track of continuity. In this respect, they are crucial to digit al production.

:

Layout

Layout is the phase of production in which the two-dimensional images and written script begin to take form in the computer. A layout artist translates the hand-drawn image by creating digital photos and properly placing sets and props. The proper scene lengths and sound files are loaded with the shot and saved as a complete file that will be passed on to the next stage in the pipeline. Figure 4 shows a storyboarded image and the layout scene generated from it.

Although layout is used most in CG productions, it also appears in commercial and feature films. An artist working on a project involving the combination of live action and CG will most likely have a camera match-move associated with each scene he is given. This file re-creates the real-world camera and set in the virtual environment. The cameras angle, size and lens must exactly match the accompanying background plate to ensure the digital elements have proper scale and perspective.

In both types of production, the character you are animating will be placed in this file. That figure will be a static object and marks the beginning of the animators duties. This will probably be the first file you touch. It should have all the necessary elements to complete the scene. There are, however, a few more steps before animation can begin.

Shot Turnover

The shot turnover process involves the assigning of a shot to a specific animator. A brief meeting occurs and the artist walks away with a shot or series of shots to complete. This is an opportunity for the lead or supervising animator to discuss the major beats in a scene and provide any additional information from the director or client. In addition, unusual technical considerations might be discussed, such as special character setups that are specific to the shot, as well as staging and camera issues. The animator should walk away with a thorough understanding of what is required.

Figure 5 shows the boards and corresponding layout file for the first three shots of the short animated film. The focus for these shots is to wake up and re-energize. The character desperately needs to finish his work and knows there is a long night ahead of him.

In addition to the attitudes the character will possess, there are technical considerations. First, the character needs to have plenty of room for his stretching routine. This will involve strategic placement of the furniture. Second, the character interacts with a few objects in each shot. Special rigs were generated to constrain his hands to both the chair and cola can. Its important to discuss these types of issues before work begins; they can influence how you approach the shot. Once these issues have been addressed, the animator can begin the process of planning her shot.

Planning

v. planned, planningv. tr.

1. To have as a specific aim or purpose; intend.

Planning involves the pre-thinking of a shot. This phase occurs before you begin to set keys. It provides you with an opportunity to flesh out ideas quickly and formulate your thoughts and ideas for the shot. These can be decided upon without turning on the computer. This will ultimately make your actual keyframing efforts more effective and efficient.

Planning might be the most import ant step in the animation process. However, its also one of the most overlooked. Many animators feel the pressures of production and jump right into a shot without the slightest thought being given to what they are trying to achieve. Ive fallen into this trap many times as well, but I constantly try to remind myself of the consequences. My animation will take twice as long and may be five times as painful to achieve. The finished product will usually be lifeless and flat.

The most important planning process you can indulge in is thinking. It sounds simple, but again is of ten overlooked. Spending 15 or 20 minutes visualizing the scene can make a big difference. I often lay my head on my desk and walk through the scene in my mind. Other animators Ive worked with spend an entire day thinking. Once the thinking phase has been completed, its time to look at some references.

Video Reference

Video reference falls into two categories: The artist can shoot footage of himself performing an action or he can use pre-existing footage for guidance. The latter is particularly important when animating something that you can replicate. For example, doing a shot of a walking elephant would necessitate actual footage of an elephant walking. It would be difficult to replicate this motion on your own. Tapes like National Geographics are easy to find in local video stores, and many studios keep their own libraries of this type of material. I also recommend beginning a collection of your own.

When dealing with human motion, shooting video of yourself or another animator can be beneficial and very simple. The only equipment needed is a cheap video camera. Spending big dollars on a high-end camera isnt necessary. The main objective is to generate a reference moves that you can study. These images can provide crucial clues to how the body actually moves during an action. In addition, nuances you might not have thought of will be realized while studying this foot age. The subtleties of human motion are amazing. Incorporating those details can make a good shot great. Consider the following example.

The three shots we are currently dealing with could use some help from the video camera. The motions that are supposed to occur are fairly complicated, and although Ive gotten in and out of a chair many times, Ive never studied the mechanics involved. The camera will shed some light on this. I found an open area, placed the camera on a tripod, and found a chair of similar style. I also tried to match the shot s camera angle. Although I couldnt match it exactly, getting as close as possible provides me with a more accurate account of how the shot will ultimately look.

Once the camera began to roll, I acted out the motion in a variety of ways. This process required doing a number of takes or versions of the action (see Figure 6). Even though its likely that no one will be watching, it might take a while to become comfortable in front of the camera. Its important to remember that you are trying to capture a performance with this reference. Your performance must match the personality of the character youre animating and come across on tape as natural as possible. Animation is acting, and this is the first step down that path.

There are a couple of important points about this reference. First, the shots had specific frame counts associated with them. This means that I must fit all actions into that time range. As mentioned in Chapter 8: Timing, a stopwatch is an excellent device to help determine your timings. I used the stopwatch during the first few attempts. Second, I shot video for all three shots at the same time. This was necessary to maintain continuity between actions. (Ill discuss this concept in more detail in a few paragraphs.)

After shooting several minutes of footage, I sat down to analyze the tape. While studying the footage, I made some interesting discoveries. These scenes involve a person whos exceptionally tired. I shot the reference at a late hour and tried to envision my mindset after a 14-hour stint in front of the computer. I found myself yawning and rubbing my eyes. A few shakes of the head were also necessary to wake up. This took care of the first two shots; getting into the chair was a different story.

I wanted to try something dynamic for the characters approach and sitting movement. Id originally thought it would be interesting to have him spin around once before settling in front of the desk. I thought this might play on his young and whimsical nature. It was definitely more interesting than just walking around the chair and plopping down, but didnt entirely fit the scene. The character is supposed to be at the end of a long day. The amount of energy required to make the spin move just didnt fit.

The solution occurred while the camera was rolling. Id finished a take or attempt at the scene and was preparing to stand up and try the scene again. I noticed the natural progression was to spin the base halfway around to place me closer to the starting point in the cubicle. I left the chair in this position and attempted another take. The tired state of my body and the inviting seat worked perfectly. I plopped down on the chair and allowed the momentum to spin my body the half turn required to meet the desk. Done. Figure 7 shows the corresponding frames. The next step is to transfer these ideas to paper.

Thumbnails

Thumbnails have been mentioned several times over the course of this text. Its a popular method among veteran animators and a process that I strongly support. This simple step can save hours of wasted effort. The only requirement is the ability to pick up a pencil and draw, no matter your skill level.

Thumbnails are small drawings that are generated very quickly and serve as a vehicle to experiment with poses and ideas. Depending on the artists skills, they can be polished characters, stick figures or scribbles on a page. The level of artistry isnt important. Its the visual cue the illustration provides you with. Even if its only understood by the artist generating it. Dont be afraid of putting your ideas on paper. If you understand them, they will be effective.

I began this phase of the planning process after spending time studying the video reference. I have around 10 minutes of footage that needs to be ordered. In addition to experimenting with ideas, the drawings initially serve as an organizational device to assemble the more successful parts of each action being performed.

The first two areas of focus were the actions occurring at the beginning of the shot. I found an interesting take toward the end of my video that involved me turning halfway around while standing in place. This felt natural and was an excellent way to reveal the character. In addition, it was a unique way of performing the action. I combined this move with a yawn from an earlier take on the tape and began the process of sketching some thumbnails of the action. Figure 8 shows the results. With this initial pass, I literally tried to replicate the posture from the reference video to get a good starting point.

If you look closely at Figure 8, youll notice some timing notes associated with each drawing. This is a terrific opportunity to begin formalizing some of the keyframe locations. If necessary, Ill use a stopwatch to help make decisions. More than likely, Ill modify these at a later stage in the production, but they give me a reliable foundation when I start setting keys in the computer. Now back to drawing.

After completing the sketches for the stretch and yawn portions of the shot sequence, I started working on the approach, positioning and sitting in the chair sequence.

Continuity

Continuity is critical in filmmaking. It ensures consistency of all the major elements throughout the film. Directors, producers, writers and designers strive to develop unique environments and personalities in their productions. They associate colors, lights, actions and emotions to those settings. Those elements must maintain some uniformity throughout or the audience will easily get lost.

As an animator, the primary focus is motion, and the most critical continuity for an animator is the matching of action and poses between shots. The character must maintain a similar gesture and position relative to camera as it cuts in, out, and around the scene. This is especially important when two shots need to correspond exactly. Such is the case with the short project discussed here.

Figure 5 shows the series of shots. Shot one involves the stretching motion, shot two is a match cut to the characters face, and shot three has him sitting in the chair. In reality, its one action with three different cameras. For the action to flow effectively, the character must maintain continuity as the camera cuts into the face, and then back to the full body.

To learn more about animation blocking and other topics of interest to animators, check out Inspired 3D Character Animation by Kyle Clark; series edited by Kyle Clark and Michael Ford: Premier Press, 2002. 266 pages with illustrations. ISBN 1-931841-48-9. ($59.99) Read more about all four titles in the Inspired series and check back to VFXWorld frequently to read new excerpts.

Series editor Kyle Clark is a lead animator at Microsofts Digital Anvil Studios and co-founder of Animation Foundation. He majored in film, video and computer animation at USC and has since worked on a number of feature, commercial and game projects. He has also taught at various schools, including San Francisco Academy of Art College, San Francisco State University, UCLA School of Design and Texas A&M University.

Series editor and author Michael Ford is a senior technical animator at Sony Pictures Imageworks and co-founder of Animation Foundation. A graduate of UCLAs School of Design, he has since worked on numerous feature and commercial projects at ILM, Centropolis FX and Digital Magic. He has lectured at the UCLA School of Design, USC, DeAnza College and San Francisco Academy of Art College.

![[Figure 1] A storyboard sequence. [Figure 1] A storyboard sequence.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/featured/2121-inspired-3d-getting-started-animated-short.jpg?itok=BQ2yD7JC)