MPC Vancouver’s visual effects supervisor Seth Maury discusses the creation of an anti-heroine’s magical world.

With Maleficent well on its way to surpassing the $200 million dollar mark domestically, to say nothing of its success overseas, Seth Maury is breathing a big sigh of relief. Along with Moving Picture Company’s Adam Valdez, Maury helped lead an international team of roughly 350 artists – 150 of them based in Vancouver - in the creation of this high profile reimagining of an animated Disney classic. From his MPC Vancouver office, the visual effects supervisor recently took some time to reflect on the thorny business of updating a classic and some of the more controversial elements of this origin story.

James Gartler: This is one of the most eagerly anticipated movies to come along in quite some time. I can only imagine for you and the rest of your team it must have been exciting to work on something that from day one was getting this much attention…

Seth Maury: It’s great to work on something this high-profile. It’s nice to have a story that people know and care about, even if we’re going to change it and not everybody’s going to be thrilled about it. It’s great to have a star like Angelina Jolie so that you know when it comes out people are going to see it. It’s nice to have all the billboards around town and to get that energy going as it gets closer to being released. It’s fun to have all that, but really it’s rare to get to work on – even if you’re reimagining it – something that you saw as a kid. It’s not something I ever thought I’d be doing when I saw the original way back when!

JG: The Moors where Maleficent lives in this film weren’t a part of the 1959 movie. How did the MPC team go about developing the look of that world?

SM: I’ll preface this by saying that the London team mostly took care of the Moors and everything inside the fairy world, and here in Vancouver we took care of the stuff in the human world. Robert Stromberg, our director, really wanted to differentiate between those two environments. When you’re in the human world, it should look like somewhere in the countryside of England, like something you’ve seen before, so that in contrast once you’re inside the fairy world it’s a completely different color palette, layout and feel. We got a ton of production art from Robert and production designer Dylan Cole and used it as a starting point for our discussions of what these worlds would look like.

JG: You also worked on Maleficent’s decrepit cliffside castle…

SM: That’s right. We called it ‘the ruins’ and that actually went back and forth a little bit between London and Vancouver. In the end, there was a practical set built for it and then it was extended by matte paintings. Here in Vancouver, we worked on the sequence called ‘Maleficent’s storm,’ when she gets really mad after getting her wings cut off and goes up to the ruins and uses her staff to shoot some green magic up into the sky.

JG: Were there ever plans to explore more of that particular location, since the Forbidden Mountains were such a big part of the original film?

SM: You know, I don’t think there were plans actually to elaborate on that further. It’s just meant to be that place where she can get away and be by herself. A little hideaway.

JG: One of the most impressive sequences in the film, for me, was Maleficent’s first face-off against the royal army. Did your team handle pretty much everything there?

SM: Digital Domain actually did the digital Maleficent, but we did the rest of the environment and all the creatures, so that was a great scene to work on. The live action was shot as close as possible to the early previs that we had. When the footage came back, we looked at the plates and strung them all together to replace the previs. Then we started the process of seeing what practical materials we had to base the scene on, and from there what we had to supplement it.

We had some art from Dylan that showed what he wanted everything to look like, which was a rocky kind of look with trees delineating the Moors. We built an environment made up of both 2D and 3D trees for the moment when Maleficent and all the dark fairies emerge. We had groomed grass for the entire ground in case we needed to do all-CG shots. There was also a skydome, a big dramatic 360-degree overcast sky, and in addition to that we had all our characters: the trolls, the serpent, the boar and the dark riders. And then we had a few variations of each so it wouldn’t look like it was all the same character.

JG: Did you have to use different software to bring each of the creatures to life?

SM: The characters mostly went through the same in-house pipeline. We animated them in Maya and we textured and lit them in RenderMan. I think a few of the guys spent some extra time with the dark rider and dark troll, because one of things we really tried hard to do was make the moss growing on them look really lifelike and accurate. We had to use two different pieces of software to make sure they moved properly. Because the characters were made of wood and were so dark, the moss gave them shape and form because it caught the light. A lot of times when you light a piece of wood, it doesn’t actually lighten up that much, so we spent a fair bit of time on the moss covering the dark rider and the dark troll. I don’t think we did it too much on the serpent because you didn’t see him in that many shots where you could tell how the moss was working.

JG: The serpent’s viper-like movements reminded me of the way the dragon struck at Prince Phillip in the climax of Sleeping Beauty. Was that supposed to foreshadow the dragon’s appearance later in the film?

SM: (Laughs) I wish I could say it did. When we did that, we were going for the coolest shot we could get from Maleficent’s POV of this snaking twisting creature that comes up out of the ground. When it first bursts out you can’t really tell what it is until the dirt clears away and you get a clean look at its face, but it still doesn’t look like a face. It was our mission to create a cool-looking shot that you hadn’t seen before.

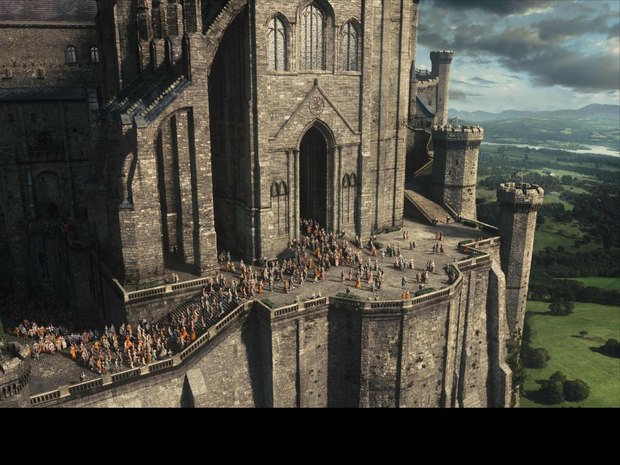

JG: MPC also created the establishing shot of King Stefan’s castle on the day of Aurora’s christening. In the animated film, it was staged like a moving tapestry. Here, the camera swoops around to make full use of the 3D…

SM: Robert wanted all the establishing shots to have big sweeping camera moves to draw the audience in. Inside the castle they used locked-off cameras, and I think for contrast, whenever we were coming up on an environment, he just wanted the camera alive all the time. So that’s what we went for.

JG: Did you find yourself going back to the original film much for reference or was it more a case of following the director’s vision for this new story?

SM: We did both actually. We definitely had discussions about paying homage a little bit to the original without being locked into anything that was in there. At the same time we did do some research on our own, and I think the place where I probably did it most was in going back to watch the original curse scene and seeing what that green magic looked like. I watched that scene over and over again to see if the magic had a character or a personality.

JG: What kind of personality would you say it has? I noticed it radiated out in a burst at the very end of Jolie’s curse…

SM: In 3D you can get a lot more detail and perspective on something. There’s a volume to it once the camera moves and that’s a lot trickier to do with a 2D drawing. The magic had a certain quality, the way it dissipated and flickered out, and went from big magic to little wisps as it got higher. I liked that. So when we were doing the curse magic, we did tests on a few different looks and then we put it in front of Robert and he gave us back a drawing of what shape the magic should take on. He called it the Parentheses. You can see in the film. It has those little semi-crescents on each side of her because of the drawing we got from Robert. So that’s where we got the idea for the effect for the crux of the curse, when the magic blows outwards. It already looked like a sphere that was ready to explode, so the curse flowed all the way to that stuff exploding at the end.

JG: Speaking of the end, I was surprised that the dragon’s fire wasn’t green, since Maleficent used green magic throughout the film. How was the decision made to go with a more traditional orange/red color scheme?

SM: Adam, Robert and I talked about coming up with rules for the different ways Maleficent used her magic. We ended up choosing to save green for whenever she was doing evil or being mischievous against people she didn’t necessarily like. So when she conjures the curse for the baby or when the soldiers come up off the ground and are tumbling through the air, that’s green magic. When she blows magic to Aurora to put her asleep or to wake her up, it’s yellow. We were trying to color-code her emotions to the magic. I think that’s probably why when you got into the dragon scene it that was just proper flame orange, because other people that she cared about were in there.

JG: There’s been some controversy around the fact that Diaval the raven becomes the dragon instead of Maleficent herself. When you guys were working on that sequence, did you think it would be a bit polarizing for audiences?

SM: I think that was a decision that happened way early on in the script, probably before I even came onto the film. But I noticed that. I mean, I’d read blog comments every now and again where people were trying to guess from the first trailer, “well no, it looks like Maleficent becomes the dragon!” and I had the feeling that people would either love it or hate it because she doesn’t become the dragon. I’m sure that people did love it and did hate it!

JG: What kind of software did you use for Diaval’s many transformations?

SM: We did the transformations for Diaval into the wolf and into the raven. We used Maya for modeling and RenderMan for rendering and we spent a lot of time in Nuke, which is what we comp with. We’d try some line-ups with the character in Maya, see how well certain positions worked, render something out, figure out what the timing should be to transform from a leg to a wing and stuff like that and then we started putting texture on it.

JG: I’d wager that transitioning from human skin to feathers must be quite the challenge…

SM: Yeah, it’s definitely tricky. The scene where we had Diaval transform from human into wolf, he had this long black coat and what was handy about that was that it could flap and approximate something that looked like feathers. The costume had a flowy quality that we could work with.

JG: The look of the forest of thorns in Maleficent really seemed to match up nicely with the one seem in Sleeping Beauty…

SM: We got some color studies from Dylan Cole to help us with the mood and shapes and he seemed to be trying to pay homage to the original. We even took his art and used it as a background image plate for one shot and just modeled right on top of it. We tried to model one-to-one with what he’d drawn and then looked at it through different cameras to see how it looked from other angles.

JG: Is it more difficult to make something that large and simple in design appear real in this environment? I’d imagine they could very easily look fake because of their size…

SM: Exactly. For us, it’s a problem of scale because a lot of shots are wide shots so you want that detail to read at a distance, which is the detail that a rose bush or thorn bush would have scaled-up, but at the same time when you come in tight you don’t actually want it to look that big. You want it to be properly scaled down and to have small detail so it looks large. So it actually was really tricky because as I was saying earlier, it’s pretty hard to light wood if it’s dark wood. If you have a bright sunlit day then you can get a highlight along it, but we had a lot of soft diffused light so it was pretty hard to get a shape out of it and a sense of scale and volume. It’s one of those things that I hadn’t thought much about before we got into it. How do you make something that everybody knows to be little pieces of wood actually look like they’re three feet wide and super-tall?

--

James Gartler is a Canadian writer with a serious passion for animation in all its forms. His work has appeared in the pages of Sci Fi Magazine, and at the websites EW.com and Newsarama.com.