A whole new area of work opened up for me just as the Soviet forces were breathing smoke around the borders of Czechoslovakia, and I made a film called The Giants that the communists banned for 20 years. For me, it was a point of pride.

An excerpt from Gene Deitchs How to Succeed in Animation (Dont Let a Little Thing Like Failure Stop You!).

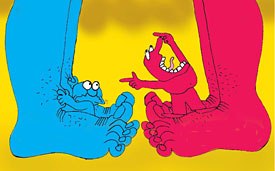

The Giants (simulated from pencil layout sketch).

By the mid-60s some conditions were beginning to lighten up in communist Czechoslovakia. I have covered all of that in my book of memoirs of what life was like in this place in those days, For the Love of Prague. To find out how I managed to have a life and how I worked under the local conditions, please check out my website.

In this book I will only go into the aspects of the communist environment that had a direct connection to my work in animation. Even though I always was and still am doing work exclusively for clients in the west, I had to actually do the work in Prague, and the spirit of the people around me certainly had its effect on the work.

The rising spirit was fed by the terrific movies of Milos Forman and Jirí Menzel, and the amazing plays by Václav Havel and others, which began to appear. It became the great Czech wave of the 60s! Suddenly the spirit caught the managing director of the Prague animation studio, and he asked me if I would do a film for them. Ive made it clear that my film work has always been mainly commercial. I dont consider myself any great creator, though I have come up with a few popular characters. I have done virtually all of my films on order for clients.

I am very good at what I call creative problem solving. I enjoy the challenge of trying to adapt the creations of others into films. So I celebrate myself with the self-dubbed title of Creative Problem Solver. Only rarely do I have the chance to create something original on my own. There were the brief Terrytoons days and Tom Terrific, and Nudnik n Prague otherwise, I have been adapting the creations of others. Now Krátky Film, the parent organization of the animation studio, and itself a division of the State Film, run by the Czechoslovak Ministry of Culture, part of the Czechoslovak Socialist (communist-run) Republic... was offering to finance an original animated film by me. Anything I would like to do! they promised. A dilemma.

The chance to do an original story, a serious animated film, was a strong lure, but [1] I could not afford to do a film that in any way might be used as or thought to be communist propaganda; [2] I could not afford to alter my status as an external representative of western producers, and not in any way an employee of the Czechoslovak government nor its film studios; [3] I could not financially afford to work for non-exchangeable Czech crowns, the local money. In the 60s I was still paying child support and alimony to my former wife. I had to earn dollars. For all those reasons, I had to reluctantly turn down the offer.

But the times they were a changing. As the 60s neared their end, Bill Snyder was weakening. His series of failures to capitalize on what we were doing had drained off his financing. We tried every sort of thing, but he wasnt able to market anything. We did an Alley Oop pilot, even a try at Uncle Wiggily. We pasted some of Snyders first films here together into a feature-length thing called Alice in Paris. I threw my former comic strip, Terrible Thompson! into the pot, changing it to Terrble Tessie! with the adventurer a girl 30 years ahead of the current trend but Snyder had foxed so many people that he had no credit in the business. Once being the Baron of Bohemia, as one of the first Americans to do business here, he left Prague with his debt-ridden tail between his legs.

My contract with him came to an end. It appeared that my days in Prague were also numbered. And then, one of those strokes of luck appeared. Remember what I wrote earlier about luck? Dont knock it. You can, (if youre lucky) make luck happen. Heres how I stumbled onto it:

Back at Terrytoons, during the short period when I was creative chief of that huge studio, owned by CBS and producing CinemaScope cartoons for 20th Century-Fox Big Time Stuff a modest young man begged to see me. He had picked up a happily over-optimistic image of me as a maker of artistic and meaningful animation movies, and hoped I could absorb what he was doing into CBS-Terrytoons distribution. The mans name was Morton Schindel, and he entered my office clutching several small cans of 16mm films. I took him upstairs to our projection theater and ran them off. They were simply childrens picture books that had been scanned and panned by a 16mm movie camera, no animation whatever, with modest storyteller narration, and light musical scores. Schindel put the best spin on these motionless movies by labeling his technique as iconographic.

I didnt know what to tell this fellow. He was so sincere in his belief that his little films would be loved by small children, and that they should be on TV. But even then and this was in 1957 such simple, quiet little films of still pictures would be almost impossible for Terrytoons to market. I tried to be sympathetic and polite to the man. These were indeed charming stories, photographed from some of the best childrens picture books.... but commercially hopeless. There would be no way I could sell this kind of thing to Bill Weiss. All I could do for Schindel was to wish him luck. But just after he left my office, a thought struck me. There was perhaps one chance to help the guy!

We were at that very moment in production on the first series of Tom Terrific films, but about six months from completion. Just a couple of days earlier I had gotten a call from Bob Keeshans Captain Kangaroo office, urging us to hurry, as they were in great need of new film material. As Schindel left I picked up the phone and dialed the Keeshan office. Here was something they might be interested in as filler until Tom Terrific was ready. They called Mort, reviewed his films, and thought they were just the things for their Captain Kangaroo show! They leased all 12 of them! So Mort got his dream of seeing his pure little childrens films on nationwide network television. I was delighted that I was after all able to help him, and was surprised to see that even after Tom Terrific went on, and had its great success, the Schindel films also continued on the show. So Mort was happy.

But of course the Captain Kangaroo show was an exception to the way kids TV was heading at that time, and Mort was forced to look to a different market to be able to continue to produce his lovely story films. Almost as an afterthought, he began to show them around to schools and libraries. There, in a market largely ignored by filmmakers, Mort struck gold. He lived in Weston, Connecticut, in a log cabin in a patch of woods, so he formed a company he called Weston Woods. Within 10 years, Weston Woods had grown to be the leading producer and distributor of audiovisual materials based on childrens literature, and developed into a complex of buildings on Morts wooded property. He was now ready to expand from modest iconographic films to full animation.

I knew nothing of all this, having already been working in isolated Prague for eight years. Mort was looking for me, ready to return my favor, but in the meantime I had disappeared from the New York map. He heard that I had been working for William L. Snyder/Rembrandt Films. The fact was, however, that my contract with Snyder had already ended.

However, Snyder being Snyder, he was not ready to just politely give Schindel my address. Of course! Gene is under exclusive contract to me, working on my projects in Prague, where I have exclusive production rights. Two full-frontal lies, but why let a little thing like truth and common courtesy stand in the way, when a lucrative deal is sniffed? The truth was that Snyder owed the Czechs a huge amount of money, and not only had no exclusive rights whatever to produce in the country, but was no longer welcome here at all. But he smoothly assured Mort that he was in a position to get his films produced in Prague, directed by me, at an excellent price. He went on to say that he liked Morts projects so well that he would personally finance half the costs, for a 50/50 split of the returns.

Sounds good? Poor Mort, didnt yet know that the price Bill quoted was exactly double the actual cost, so that Bill would be getting a 50/50 split of the income from the films without actually investing a nickel. Weston Woods would be in fact paying the full cost! Bill was also counting that I would be so hungry, which I was, and so eager to do high quality childrens films, that I would be willing to work for peanuts, and not spill the beans to Mort. He managed to pull it off.

I knew the true cost of animation production in Prague. After all, the studio producer was my wife Zdenka. But I was in an ethical bind, not feeling able to directly tell this new client that he was being shafted. I had to let him find that out for himself. Unfortunately for Bill, he inadvertently left a copy of a letter to Czechoslovak Filmexport, giving the actual price of the productions, in a script, where Mort came across it.

When next we spoke, I was able to fill in Mort on the facts, and from then on was able to work directly with him. Otherwise, I would have had to quit after the first two films. Snyder, for no investment and no input of any kind, would have gotten half the income from every film I did for Weston Woods, and I would have been limited to a peanuts, one-time direction fee. As it was, even after finding that he had been taken, Mort honored his contract with Bill, who got his unearned share of my first two Weston Woods films, (Drummer Hoff, and The Happy Owls), for the next 30 years! Only then did his son Adam right this wrong, and rewrote the contract to repay me for all those lost royalties.

You may feel that I have rambled far from the assumed subject of this chapter, but all of this will fit together. You will see, as if you didnt know, that seemingly unrelated events, happening over a long stretch of time, can come together in unexpected ways, and with both good and bad results. Such was the case here. The arrival of Schindel in Prague in early 1968 coincided with the great euphoria of the Prague Spring, the Socialism with a human face of Alexander Dubcˇek. But the Soviet-led invasion was coming in August to smash it. It seemed that our lives were at a crossroad and they were but when all that had played out, there followed a 25-year period of maximum creativity and honors with Schindel and Weston Woods. That will all be the subject of the next chapter.

But first, back to the dilemma of the offer by the Czechs to back an original film by me. I didnt want to offend them with an all-out no. I just said that I couldnt afford to do a film without a hard currency backer. But that didnt stop me from thinking about the idea, and a statement I had long wished to make about the futility of violence violence begetting counter-violence. The seemingly endless blow and counter-blow between Israel and the Palestinians was on my mind.

It had been going on a long time already in the mid-60s, and as of this writing it is still going on. So even though I couldnt make such a film for the Czechs, (The Prague government at that time strictly backed the Palestinians no even-handed story about that could possibly be filmed here, however I might mask it.) But I nursed a hope that I might someday find a backer, so I worked up a storyboard. I titled it, The Giants.

It was to be staged with symbolic characters, two equally ugly, snarling, spitting dwarfish figures, one solid blue and the other a flaming magenta, on a deathly landscape. They hurl venomous insults at each other, to the constant, irritating, rasping sound of locusts. One dwarf loudly calls out the name of his protector. Thunderous, earth-shaking footsteps are heard, and giant feet and legs, the same color as the summoning dwarf, stride in and stand behind him. Then the other dwarf turns and calls out the name of his protector. More thundering footsteps, and a giant of his color strides in. Then the two dwarfs goad each of their giants to engage in a series of blows and counter blows.

After numerous drastic exchanges, and a devious peace conference, the two giants ultimately abandon their two irreconcilable clients to fight it out by themselves. But the mean-spirited dwarfs have no stomach for personal battle, and so cling together in a terrified embrace, repeatedly moaning, How will we get along without our protectors?

While discussing the first childrens book adaptations Mort wanted me to make for his Weston Woods company, he spotted the Giants storyboard on my desk. One look at it and he offered to co-produce it. Exactly at that moment, the democratization was blossoming in Prague. Suddenly, the idea of doing something for the Czechs was OK. The country was becoming democratic, and I would be able to be paid in the dollars I needed. Weston Woods would pay me, and the Czechs would finance the animation production! So I plunged in with high enthusiasm.

I got the wildest designer in the country, Vratislav Hlavat, to give the film the highly bizarre look the story demanded. Hlavat was not only a wild designer, but also a wild adventurer. He and few other hot-eyed pals were flying on natural gas in homemade balloons! I brought in my most promising assistant, Milan Klikar, to do the layouts. Then, just as we were ready to begin animation, the Russians came in! After a week of terror, I put Zdenka and the Giants layouts in my little Saab car, and drove over the border to Austria. I couldnt take a chance of being expelled from the country, and having Zdenka, still a Czechoslovak citizen, locked in.

As the Soviet occupation set in, and the democracy movement stalled, but not yet crushed, we were assured we could continue with the film, and were urged to return. In fact, the then leaders of the studio were eager to see the film finished before censorship would be restored. So it became a passionate challenge. When the film was finished it was a sensation in the Czech cinemas. Even though my story was inspired by the conflict in Israel, and had nothing whatever to do with the Czechoslovak political scene, or the Soviets, nevertheless, in the current dramatic situation the local audiences saw the red giant as the image of Moscow, and the blue giant as the image of America... It was illogical, as the film showed both dwarfs and both giants as totally amoral.

With great enthusiasm, the Czechs entered The Giants in the San Sebastian, Spain International Film Festival, and it won the Grand Prize, not only over all other animated films, but also over all films in the festival! We knew we had a winner. I admit that world sympathy for the plight of Czechoslovakia at that time was a powerful plus, and knowing how such emotional factors influence Oscar voting in Hollywood, we felt sure we had a winner there too... and hey, I do think The Giants is my most powerful film. But Schindel, being in the school film market, had no experience with the qualification procedures necessary for an Oscar entrant, and he muddled it. The film never got entered in the key year when considering the world sympathy for this country it had every chance of winning.

Again, there just had to be final blow. The newly installed hard-line communist government immediately banned The Giants. I could see no logical reason, and I assumed they banned it more for the way Czech audiences reacted and cheered it, than for anything actually anticommunist in the story. But no one ever said anything to me personally. Zdenka tried to find out the official reason why my film was banned, and was finally told that it had been labeled objectivist. That was a new word for me. I knew about objective, but what in the world was objectivist? It soon became clear.

The communists always had everything neatly labeled as correct and incorrect. There were imperialist aggressors and the camps of peace. They were not interested in exploring both sides of anything, nor any shades of meaning. My film pointedly did not show either side as the aggressor, and thus in the communist view it was not instructive to the audience; it left the audience room for interpretation... it was objectivist!

Schindel, as co-producer, still had the rights to the film in western countries, but the truth was, in spite of his enthusiasm for it, Weston Woods, with their childrens story films catalog, had no real slot for it. A few copies were sold and successfully used in higher-grade social studies classes, but that was about it.

The fact that I had a film banned by the communists became a point of pride for me. The film languished in the locked cases of the banned films archive for 20 years. After the 1989 restoration of democracy, I received, together with the band of other, more important film directors of previously banned films, a certificate of apology and a token compensation for lost royalties, 2,000 Czech crowns, about $55, as symbolic recompense for 20 years of lost royalties! Come and visit me sometime and I will show you my long-lost film, The Giants.*

*Editors note: The Giants was in fact shown at the Ottawa International Animation Festival in September 2000.

To read more about Genes adventures in the animation world, visit Genes .

Gene Deitch is one of the last surviving members of the original Hollywood UPA studio of 1946 and the instigator of the CBS-Terrytoon renaissance of 1956-1958. He was also: animation department chief of the Detroit Jam Handy Organization; 1949-1951, creative chief of UPA-New York, 1951-1954; director at John Hubleys Storyboard, Inc., New York, 1955; president of Gene Deitch Associates, Inc., New York, 1958-1960; creative director for Rembrandt Films, 1960-1968; and star director for Weston Woods Studios, Inc., Weston, Connecticut, 1968-1993. He has worked for more than 40 years with the Prague animation studio, Bratri v Triku.