UCLA Greek literature professor Dr. John Rundin conducts a lively review of Disney's feature adaptation of the traditional Greek fairy tale.

Editor's Note: For our review of Hercules we asked Dr. John Rundin, a University of California at Los Angeles Classics Professor, to compare this beautiful Disney romp to the ancient classic tales.

If the film Hercules had told the story of Hercules as it was known to the ancients, the Disney Corporation would be in far more trouble with the Southern Baptists than it is now. Perhaps the Baptists might have overlooked Hercules' vocation for homicide. In the course of his life, he was responsible for the death of, among others, his first wife Megara, three of his children, his girlfriend Hippolyta, his martial arts instructor Chiron and his music instructor Linus. Conservative eyebrows might have been raised, however, at the circumstances of Hercules' conception. He was conceived when Zeus, though married to Hera, made love with Alcmene in one of his numerous adulterous dalliances; Alcmene was a happily married woman, and to overcome her scruples Zeus had to fool her by disguising himself as her husband. Hercules' own sex life would certainly have been found objectionable. In one exploit, he is reported -- while drunk, yet -- to have impregnated the fifty daughters of Thespius in a single night. Certainly the Baptists would have felt obligated to censure his transvestitism while he served as the boy-toy of Queen Omphale, not to mention his enthusiastically pederastic affair with the boy Hylas.

Divine Inspiration

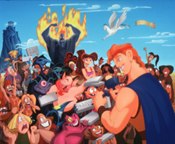

None of this adult material makes it into Disney's highly entertaining children's movie, Hercules, which has only scattered and garbled points of contact with the ancient tradition. In the ancient stories, Hercules has to rescue his new bride and second wife, Deianeira, when the centaur Nessus tries to rape her as she rides across a river on the centaur's back. In the Disney version of the story, Nessus is wading through a river and carrying on with Megara, who, according to the ancients, is Hercules' first wife, when Hercules comes upon the two of them and, seeing Megara for the first time, tries to rescue her from the centaur. This is typical of the way that Hercules uses the ancient sources. It takes a bit from here and a bit from there and assembles the bits into a new whole. In the Disney story, Hercules rides Pegasus, fights the Minotaur and encounters the Gorgon. In the ancient tradition these are the deeds of other heroes. There is much pure invention in the film as well. The satyr Philoctetes, a cutesy Disney innovation, serves as Hercules' trainer. The treatment of ancient art is much the same as the treatment of ancient narrative. Obviously, the creators of Hercules spent some time looking at Greek art as they did reading Greek stories of heroes. Clever takes and parodies on Greek vases, sculpture and architecture abound in the movie. Yet these details are subordinate to a modern artistic vision. This inventive recycling of ancient narrative and art is not bad, and, in fact, not too different from the ways in which the ancients themselves constantly reworked traditional materials. But don't imagine you will learn much about the Classical world by viewing the movie; it's far more concerned with modern life in the United States.

Mortal Concerns

The traditional tales of Hercules involve themes of human importance. They can be read as meditations on the ambivalent nature of the violent hero. As Timothy McVeigh returned home from the Gulf War a military hero and, subject to delusions, killed hundreds of his fellow citizens in a bizarre parody of a military action, so Hercules returns home from his own heroic exploits and, in a fit of insanity, mistakes his first wife and his children for enemies and slaughters them. In general, the violent hero's values are incompatible with domestic happiness. Hercules meets his agonizing mortal end when his second wife, Deianeira, using a potion on him to rekindle his passion for her because, like a good Greek warrior, he has taken a mistress while away at war, accidentally poisons him. Hercules' life can also be read as an expression of human hopes for salvation. He is born the bastard son of Zeus and a mortal woman. Hera, Zeus' wife, hates and persecutes him throughout his life because he is a product of her husband's infidelity. What better image of the human condition, caught as it is between divine aspirations and physical needs, than Hercules, who was of divine birth, but somehow disinherited, alienated from his divinity? Hercules incarnates humankind's struggle with its innate physicality, powerlessness and inadequacy. He is obsessed with food and sex. He is forced to play the low-status role of slave to his wimpy cousin Eurystheus, who, through Hera's malign cunning, enjoys a kingdom which was supposed to go to Hercules. Hercules is sometimes portrayed as rather dimwitted and never as particularly bright. Amazingly, however, through plodding labor and discipline, he manages to reclaim his divinity. He alone of all mortals is welcomed after his physical death into the company of the Olympian gods, where he resides accompanied by his divine wife Hebe. There's hope for us all!

Modern-Day Metaphors

You won't find much of this stuff in Disney's Hercules. Instead we find modern American psychopathologies. Disney's Magic Kingdom has little more tolerance for moral complexity and ambiguity than the most red-faced audience member on the Jerry Springer Show. The film's treatment of Meg, Hercules' love interest, is an apparent exception to this principle. A surprisingly liberated heroine for a Disney animation film, she is, of course, under the influence of the satanic Hades. There can be no other explanation for her assertiveness. Aside from her, things are black and white. Disney's Hercules, unlike the ancient Hercules, is pure good. And evil is not only external to him but to his nuclear family as well. He is the legitimate son of a loving father Zeus and a loving mother Hera, whose cloying interactions make Ward and June Cleaver's relationship seem complexly nuanced. Evil is instead located in the sorts of places Americans like to imagine it - among big-city inhabitants like those of Thebes, a barely disguised New York. The Thebans' dark beards and often swarthy skin tones contrast well with the blue-eyed, light-haired members of Hercules' Olympian family. Evil is concentrated particularly in the film's bad guy, Hades. His resemblance to a Jewish Hollywood agent is a nice foil to Hercules', well, Aryanness.

The aesthetic and marketing choices of Hercules' makers have apparently led them to pander to the values of white suburbia with its Leave to Beaver family values, its distrust of big-city minorities and its large disposable income. Hercules winds up an entertaining, witty and safe children's tale of male adolescence in the suburbs. It even features what appears to be the filmmakers' anachronistic vision of an ancient shopping mall -- a colonnade where ancient Greek youths, who, strangely, toss around a discus as if it were an archaic frisbee, hang out like their modern suburban counterparts. The film's background music, provided by the gospel chorus of Muses, is as modern in spirit as any that could be heard in suburban America. If one excepts centaurs and satyrs, the Muses are the only patently identifiable members of ethnic minorities in the film. They're African-Americans, and they're neatly segregated into their familiar niche in the suburban landscape -- they're entertainers. Which is just fine. You wouldn't want Hercules to marry one of them, would you?

John Rundin received a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley,) in Classics. He is now a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA.)