Fred Patten takes a look at this new book cataloging Spike & Mike's festival compilations and well as other notable edgy indie shorts.

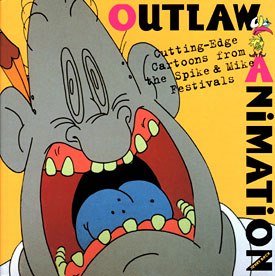

Outlaw Animation: Cutting-Edge Cartoons from the Spike & Mike Festivals.

This art book is both an authorized history of the Spike & Mike Festivals of Animation, to celebrate their 25th anniversary, and a superficial but decent overview of those animated films that are personal creations by individual cinematic artists, rather than corporate products mass-produced for maximum commercial potential.

Outlaw Animation has all the virtues, and some of the flaws, of the best authorized biographies. It tells the complete story of the famous (or notorious) Spike & Mike animation festivals, and it seems to do so objectively. Spike & Mike have always flaunted a raunchy, collegiate, in-your-face approach, and it is boasted of in the book in all its garish, flatulent detail. Mid-’70s college housemates Craig “Spike” Decker and Mike Gribble started out by promoting Southern California rock-and-roll bands. Within a couple of years, they evolved to presenting midnight screenings of films of the bands’ performances, then added funky old cartoons as curtain-raisers, then realized that the cartoons were more popular than the concerts and dropped everything except the animation.

S&M (what a double entendre!) saw that their spaced-out midnight viewers loved a wild party atmosphere as much as what was on the screen, so throwing a large plush bunny into the audience to be torn apart was done more than once. “The Bad Tie Contest was a standard event,” Beck writes on page 22 of the book. “And once, wearing a fencing mask while swinging from the ceiling, Mike invited people to throw money at him. Every night was a free-for-all.” The book is studded with photos: their grungy college commune in the mid-’70s, Spike in a cowboy costume promoting the Festival, Spike & Mike with animator Will Vinton posing with toy(?) machine guns, Spike with Festival alum John Lasseter at the 1995 Academy Awards where Lasseter got a Special Achievement Oscar forToy Story, and much more. Mike died of a heart attack during chemotherapy treatment for cancer in 1994, and Spike has carried on in both their names.

Spike & Mike’s first festival in 1977 was a composite of individual student films like Marv Newland’s Bambi Meets Godzilla (1969), foreign art films like Hungarian Marcell Jankovics’ Sisyphus (1974) and old American theatrical cartoons unseen for decades, which the two knew would blow modern college students’ minds like the Fleischer Studios’ Betty Boop cartoon Snow White (1933). This was fine until the supply of existing “outrageous” animation was used up. Spike & Mike began to haunt art colleges with animation departments to scout out promising student films. This enabled them to become friends with many talented students who would go on to become leading professional animators a decade or two later. In many cases S&M liked what they saw so much that they bankrolled the young filmmakers’ projects. Many of those now-famous animators recount their own stories in Outlaw Animation.

For those who want to know every thing about the Spike & Mike Festivals, this book presents an art-quality color gallery of every poster (with artist’s credit) for both the regular Festivals from 1977 and the Sick & Twisted Festivals from 1993. There is also a complete filmography of every title shown at any S&M Festival from 1977 through 2002.

The history of the festivals gets the first 20 pages. “The Roots of Outlaw Animation” is a brief history of non-juvenile animation in America. It surveys animation pioneer Winsor McCay’s 1910s films for vaudeville audiences, the naughty Betty Boop and Wolf & Red Tex Avery cartoons of the ‘30s & ‘40s, UPA’s artistically creative limited animation in the ‘50s, non-Hollywood art films of the ‘60s, like the Oscar-winning The Critic (1963), and the adult violence and eroticism exemplified by Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat (1972) and Coonskin (1975).

“Gallery of Independent Animators” is “a sampling of some of the field’s more important figures, all of whom have been represented in the Spike & Mike Festivals.” Each creator gets one or two pages with a capsule biography and an art-quality frame illustration from one or more of his/her most famous films. The roster includes Frédéric Back, Bruno Bozzetto, Sally Cruikshank, Michael Dudok de Wit, Paul Driessen and nine others including the National Film Board of Canada and Yugoslavia’s Zagreb Studio.

“The Top Ten Spike & Mike Festival Cartoons of All Time” are two-page profiles of the top audience favorites which fans demand to see over and over, many of which have gone on to launch TV series: Bambi Meets Godzilla, Mike Judge’s 1992 Peace, Love and Understanding, which introduced Beavis and Butt-Head; Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s 1995 The Spirit of Christmas, which introduced the South Park cast and similar classics.

These classic characters made their debut at Spike & Mike. South Park © Comedy Central. Courage the Cowardly Dog © Cartoon Network.

These classic characters made their debut at Spike & Mike. South Park © Comedy Central. Courage the Cowardly Dog © Cartoon Network.

“Even More Independent Films” presents one sample panel from each of another three dozen festival favorites, including several Academy Award winners or nominees such as Chris Wedge’s 1998 Bunny.

“Outlaw Animators Speak” finishes the book with three- to eight-page interviews with Bill Plympton, Mike Judge, Craig McCracken, John Lasseter, Marv Newland, Don Hertzfeldt, Peter Lord, Danny Antonucci and Andrew Stanton.

The Spike & Mike Festivals have become such a long-running, omnipresent tradition that today’s animation buff can be forgiven for feeling that they are the be-all and end-all of “outlaw animation.” The book does mention a couple of others in passing, although only as they relate to Spike & Mike. (E.g., the duo were doubtlessly partly inspired by a 1976 one-shot Fantastic Animation Festival in Laguna Beach, for which they handed out flyers.)

Since Outlaw Animation does not profess to be a complete history of non-commercial animation, it is unfair to criticize it for omissions such as Oskar Fischinger’s abstract-art animation of the 1930s or Yoji Kuri’s minimalist gross-out international animation festival favorites of the 1960s. Outlaw Animation is excellent as an all-you-want-to-know catalog and history of the Spike & Mike Festivals of Animation, and it is as good a survey of independent animation short films as anything else in print today.

Outlaw Animation: Cutting-Edge Cartoons from the Spike & Mike Festivals, by Jerry Beck. Foreword by Todd McFarlane. NYC, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., June 2003, 160 pages; ISBN: 0-8109-9151-9 (trade paperback; $23.95).

Fred Patten has written on anime for fan and professional magazines since the late 1970s. He wrote the liner notes for Rhino Entertainment’s The Best of Anime music CD (1998), and was a contributor to The World Encyclopedia of Cartoons, 2nd Edition, ed. by Maurice Horn (1999) and Animation in Asia and the Pacific, ed. by John A. Lent (2001).