The director of the Annie Award-winning 2D feature, his first animated film, about a lonely dog who buys a robot companion, discusses how his live-action experience helped him focus on crafting emotionally nuanced character performances.

Spanish live-action filmmaker Pablo Berger is used to experimenting with different methods of storytelling. His multi-award-winning film Blancanieves was shot entirely in a 1920s-style black and white. His film Abracadabra contains aggressive camera motion and angles, and Torremolinos 73 was shot in the style of a 70s camcorder.

But despite Berger’s open mind and eclectic filmmaking vision, he never saw himself becoming an animated film director. That is, until his comic collecting saw Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams land right in his lap.

“I collect books without words, and when Robot Dreams fell into my hands over 10 years ago, I thought it was amazing,” remembers Berger. “It was fun, and I put it on the shelf with my favorite graphic novels. I made two live-action movies and, after finishing my previous film, I was in my office just having a coffee and went back again through the pages of Robot Dreams. But, this time, I knew that I was visualizing the film in my head while I was reading it. And when I got to the end of the graphic novel, I was completely moved. It brought tears to my eyes, resonated deeply inside of me, and I wanted to tell this story. And the only way I could tell the story, a friendship story about a dog and a robot in the anthropomorphic world of New York, was to make an animation.”

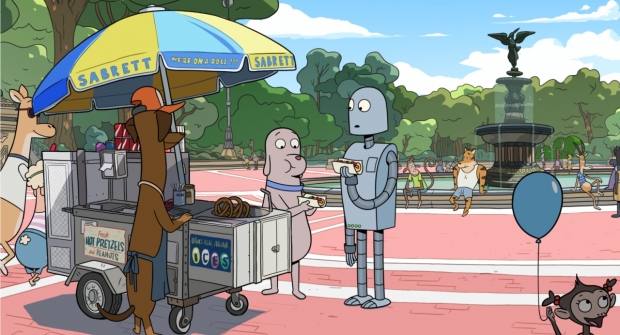

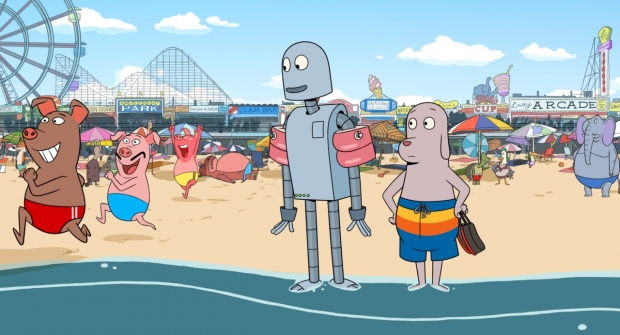

Robot Dreams is set in New York City, sometime in the 1980s. In the film, a lonely dog spots a TV ad selling a robot companion and immediately orders it. After putting the robot together, the pooch and his new bud head out and explore the city, encountering life, music, companionship, and joy that had been missing from the dog’s life until then. During a pleasant visit to Coney Island, Robot dries up, becomes paralyzed, and gets stuck on the beach. Dog is sadly forced to leave Robot there until the beach re-opens in the summer. As the seasons pass, Dog tries to find new friends, while Robot can lie on the beach with his dreams. Will the friends ever find each other again?

The film, which Berger categorizes as a musical reminiscent of the shorts from Disney’s Silly Symphony, came out of left field this year, so to speak, and took up residence in the hearts of critics and viewers. So much so, that Robot Dreams nabbed an Annie Award win this past Saturday for Best Animated Independent Feature and is one of the five films nominated for Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards, taking place Sunday, March 10. Finals voting for the Oscars ends at 5 p.m. PT on Tuesday, February 27.

“When we got the news, we couldn't believe it,” says Berger. “The first step was to premiere at Cannes. For a filmmaker, that's always El Dorado. It's a dream to go to Cannes. The next step was Annecy, the Cannes of animation, and we got a big award there. Then, it continued to the point where our film has been to over a hundred festivals. I feel honored to be part of the group of six people who came together all those years ago to make this film.”

Berger’s first animated film production began with Vikingskool’s José Luis Ágreda as art director; My Father’s Dragon’s Maca Gil as storyboard artist; Blancanieves’ Fernando Franco as film editor; Yuko Harami, who had also worked on Blancanieves, as music editor; Paul Rivoche, recommended by Ágreda, as background designer; and Berger as their fearless leader and director. The team of six worked on thumbnails and storyboards for over a year until they had their first story reel.

“I was scared,” Berger admits. “But I think to be scared is a positive for a filmmaker, because you have to get out of your comfort zone. You have to try new things. And that's what I've been doing on every project I've made. So, this fear, I made it into excitement.”

That excitement was also fueled by the team’s partnership with Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon, known for The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea, The Breadwinner, and Wolfwalkers. But the COVID pandemic threw a wrench in the alliance.

“Cartoon Saloon loved the project,” explains Berger. “We were closing the deal and the agreement, and suddenly the world collapsed with the COVID pandemic. Suddenly, the calendar for Cartoon Saloon and their projects was uncertain and we couldn’t make the film with them. So, we decided to make what we called a pop-up studio. We had to buy the computers, get the office, get the software, get the animators, and create an animation studio.”

Lokiz Films was created solely for the purpose of making Robot Dreams. Though the pop-up studio has disbanded since the release, it was a bustling workforce during production, according to Berger, with 100 animators in both Madrid and Pamplona offices. “I didn’t want people working remotely,” says Berger. “Even if it meant we all had to wear masks, I wanted everyone in the offices together so I could work closely with the animators. It was difficult, super difficult, but it was worth it.”

Berger saw working with animators as similar to working with actors on a live-action set, which is why he wanted everyone in the room together. To him, the animators are like actors, responsible for making the performances of the animated characters land in just the right way.

“The first thing I said to myself when I decided to do an animation was, ‘What can I bring from my live-action experience?’” says Berger. “Right away, I thought, ‘I can bring good performances.’ I'm used to working with actors and I have the sense to find true, deep, and profound emotions in live-action cinema. I think most animated films are comedies or action films. There are very few that deal with human emotions in a profound way. We know, of course, Miyazaki and Ghibli have been doing it for years. But, in general, there are few, and many times when I see animated films, I have a feeling that the characters overact, or that the creators think the animation will save the performance.”

Berger’s motto throughout the production was “less is more;” he concentrated mostly on the eyes of ROBOT and DOG, especially since there’s no dialogue in the film. While 3D animation would have certainly given the director’s storytelling more to play with regarding the eyes, he had decided early on that he and the team would make the most of traditional 2D.

“I'm old school,” says Berger. “Some of my favorite memories of as a kid comes from watching 2D animation, hand-drawn films from Disney and Japanese animation. And I've always been an animation fan. So, it was always a 2D project because I felt it would be more embracing. Also, the film takes place in the '80s, so it made more sense that it would be animated in 2D.”

And though the partnership with Cartoon Saloon had fallen through, Benoît Féroumont, who was animation supervisor on The Secret of Kells, came onto the film as animation director. He brought some 2D wizardry to the production from his time working with Cartoon Saloon and creatives like Sylvain Chomet.

“Benoît also worked on The Triplets of Belleville and that is one of the greatest hand-drawn films ever made,” says Berger. “Our film is also a love letter to comics. I love comics and I collect these books, as I’ve said, so it had to feel like a comic translated into cinema. So, everything is in deep focus, and we don't have a lot of camera movements.”

Berger’s team also partnered with Arcadia Motion Pictures, who helped produce Berger’s live-action films, as well as Noodles Production and Les Films du Worso, to produce Robot Dreams.

“The producers at Arcadia Motion Pictures always encourage me to go further on my previous films,” says Berger. “If there's a trademark in my cinema, it’s that every film is very different from each other. So, honestly, my producers were not surprised when I wanted to make Robot Dreams. They said, ‘Okay, Pablo. Let's do it.’ And they were able to finance it. Five years later, the film is out there.”

And winning awards left and right. In addition to its Annie win and Oscar nominations, Robot Dreams was also the winner of two Goya Awards, presented by the Academy of Cinematographic Arts and Sciences of Spain, for Best Animated Film and Best Adapted Screenplay.

Berger admits their Academy Award nomination is “the gigantic cherry on top,” but not just for the global recognition.

“For me, awards and nominations translate to more people being aware of the film, and more people going to see the film,” he shares. “That's the biggest prize for a director. For example, in Spain, the following weekend after the nomination, we had over a 130 percent increase in spectators for the film in theaters.”

As independent animation continues to rise after COVID forever rocked the productions of larger studios, Robot Dreams standing alongside contenders like Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron and Sony’s Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, could speak volumes to what creatives outside of the main industry circles can achieve.

“This production was a combination of people with no experience in animation and people who are very experienced in animation,” Berger notes. “And I think what we ended up with was a different way of making films. There was no limit. I think not knowing the rules allowed us to create a new pipeline and a new way of doing things. Honestly, I’m wondering if there was an animation director in me this whole time.”