Animation supervisor Takeshi Honda and GKIDS president Dave Jesteadt discuss the emotional impact of what may be the famed director’s final film, his first in 10 years, a semi-autobiographical fantasy set in World War II that embraces life, death, and creation, in tribute to friendship, releasing in U.S. theaters December 8.

Famed animation filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki is back in cinemas after a 10-year absence, not with a bang but with a wail. In the opening sequence of his new film, The Boy and the Heron, sirens blare as a hospital burns to the ground and an 11-year-old boy, Mahito, braves the flames and rampaging crowds in a desperate attempt to find his mother. As Mahito shouts her name, audiences already know his effort is in vain.

It’s one of the only scenes in Miyazaki’s latest triumph - and his only dark comedy - totally void of humor. The other is toward the end, when Mahito is violently pulled away from his stepmother in a storm of wind and paper. And though animation supervisor and animation director Takeshi Honda notes the first sequence was one of the most rewarding to work on in the picture, it was this second sequence that truly hit home.

“There’s this crescendo throughout the scene as this mother and son call out each other’s names before being pulled apart and I was going through a similar situation during that time,” Honda shares. “My own mother had just been told she had cancer.”

He continues, “It was a very challenging time because we were in the midst of a pandemic. It was far from over. And Miyazaki-san would say to me, ‘Go home. You need to be with your mother.’ But she was in a hospital and because it was a pandemic, they wouldn't accept any visitors from outside of the prefecture. So, I wasn't able to be with my mother when she passed away the following year in May.”

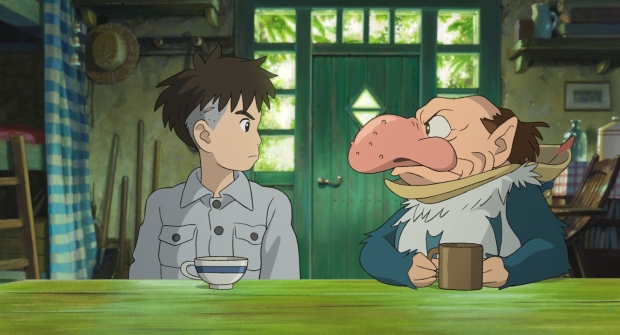

Originally titled How Do You Live? (Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka) and inspired by a book gifted to him by his mother, Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli film, releasing in U.S. theaters on Friday, December 8 via GKIDS, is a semi-autobiographical story that follows character Mahito Maki, still yearning for his deceased mother as his father attempts to give them all a new life with his union to Natsuko, Mahito’s mother’s younger sister. Though Natsuko attempts to bond with Mahito in their new country home, the boy’s grief leads him to retreat into solitude and self-harm. That is, until a talking heron beckons Mahito to an abandoned tower at the edge of the estate, noting that his mother is “awaiting your rescue.”

Mahito thus begins a warped journey through time and space, navigating a world dominated by large birds and one that’s shared by the living and the dead. As the boy braves carnivorous pelicans, blood-thirsty parakeets, and joins a mysterious fire-wielding girl in her efforts to save unborn souls, Mahito learns what it means to live after immeasurable loss and find joy in living, despite who has been left behind in death.

“Miyazaki has a lot of thoughts he wants to share about his childhood, the state of the world, and also where he is as a creator, and what it will mean for the next generation of filmmakers to follow and take the lead,” says David Jesteadt, president of GKIDS, the animated film’s distributor, which celebrates its 15th anniversary this year and has a long-time partnership with Studio Ghibli. “He's genuinely pushed to create. This film took six years to make, the studio entirely funded it, and they said they wouldn't set a release date. They wouldn't even set a completion date. There was no schedule at all, and Miyazaki could do whatever he wanted with this film. It was an incredibly supportive environment for the master himself to do with this story what he wanted.”

But, despite the freedom, it’s possible that even Miyazaki didn’t know the full poignancy of his film and the effect it would have on his own creative team, as people like Honda felt the full weight of the film’s focus on death and choosing to live on and make the most of a life still to live.

And the artist’s experiences during the film’s production make his choice to accept Miyazaki’s request he carry on as animation supervisor – despite being slated for another project – even more astounding.

“I was working on a short that was also directed by Miyazaki-san, Boro the Caterpillar, and it was during this period that he came to me,” says Honda. “He knew that I was planning to work as supervising animator for Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time but, nevertheless, he approached me and said, ‘I want you as supervising animator on this new project of mine.’ At first, I thought, ‘Maybe I'll do both?’ But it's impossible to be a supervising animator on two pictures simultaneously. So, I had to make a choice. And since it might be Miyazaki-san’s last picture, that’s what made me choose this project instead.”

It turned out to be the right choice, in Honda’s opinion, as the film spoke to the unexpected circumstances involving him and his mother, providing him a chance to sort through the emotions that came with her passing by helping tell a story that’s as humorous as it is sincere.

“There’s an intensity in the movie that comes from those topics,” says Jesteadt. “But it's also, I think, the funniest film Miyazaki’s ever made. You get the full range of the human experience with the highs and the lows together.”

The scenes that focused on the connection between mother and child left Miyazaki feeling extra emotional pressure as well, according to Honda, who experienced some kinship with the director as he went back and forth with the art department on the details of the scene where Mahito approaches a sleeping Natsuko, laying on a couch inside the tower. As Mahito reaches out to touch her, Natsuko begins to melt, eventually turning entirely into liquid and dissolving before Mahito’s eyes. It’s one of the first times Mahito begins to realize his attachment to the stepmother and aunt he’s previously rejected over and over again.

“This story was especially labor-intensive for us with all the wind, fire, and water we had to animate,” notes Honda, who has previously worked with Miyazaki on films like Ponyo and The Wind Rises. “But this scene in particular felt very important to Miyazaki-san. I think the emotion he harbors for that moment was really weighing on him because he would tweak our work a lot. He would come back to us and say, ‘No, this is how much Mahito should touch Natsuko,’ or ‘This is how Natsuko should dissolve.’ There was a lot of going back and forth between us and Miyasaki-san in this scene to keep it true to the storyboards.”

Honda also explains that Miyazaki, over the last almost four decades, has never been one to shy away from labor-intensive filmmaking.

“What is challenging about working with Miyazaki-san is the fact that he won't abbreviate,” says the animation supe. “Usually, with other pictures, you might see the camera shooting the characters from a certain angle so that you don't have to draw details or certain features that are outside of the frame because you're shooting from that particular angle. But Miyazaki-san doesn't avoid making those details.”

And that highly sophisticated style only grew and intensified with this story, rooted in truth from Miyazaki’s own life.

“Because this is quite different from the other Miyazaki titles, in terms of the visual tone that we're aiming at, it's a little bit more realistic in animation in comparison with his other films,” says Honda. “Although it does become increasingly comical as the story progresses, it does have quite a more serious tone to it.”

Which is why the details had to be included and drawn and animated just right. It made the scene where Mahito is trying to outrun a horde of pelicans exceptionally trying for Honda and his fellow animators.

“Oh, the pelicans,” he recalls. “That was hard. The pelicans were the biggest challenge in the film because you have to really think about, and draw carefully, the bone structure to get the image of that animal right. And imagine doing that for all those pelicans.”

Still, after all the pencil blisters and hand cramps, Honda is proud of the work he and everyone at Studio Ghibli created over the last six years. And their efforts show through the fact that The Boy and the Heron, despite not having any promotion or any traditional marketing campaigns, grossed $13.2 million (1.83 billion yen) in its opening weekend in Japan, becoming the biggest opening in Studio Ghibli's history, surpassing Howl's Moving Castle. The film was also the first to completely sell out at SCAD Savannah Film Fest, where Jesteadt was present for a special screening ahead of the film’s official North American release.

“There was a point last year where we were invited to Ghibli to see the film before they had finished all the sound recordings,” recalls Jesteadt. “When the lights went down in their screening room, and the Ghibli logo came up with a 2023 copyright on there, it brought up some tears. This was something I did not think I would ever see. Separate of GKIDS, separate of any business interests whatsoever, just as a fan, and as a person who just likes great film, that's something I don't take for granted. So, I've asked to see it again and again.”

Jesteadt himself has seen the film over 20 times. Though that number may not be achievable for theater viewers, seeing the movie more than once is what Honda recommends.

“We want you to see everything because there is nothing superfluous in there,” says Honda. “There are no unnecessary scenes. With each cut, Miyazaki-san and I both remember what happened behind the scenes, what the thought process was, what it took to make those scenes, who did it, who was in charge of it, and how hard it was. I remember all of this so clearly. That's why I want everybody to see everything.”