In Part 2, Christopher Panzner looks at how independent producers have to be a vertically-integrated individual as well as a little of a cowboy to survive in the industry.

The most eagerly awaited movie at last years Cannes International Film Festival was not the controversial Fahrenheit 9/11 but 2046, a mysterious feature film that celebrated Chinese director Wong Kar-Wai had been working on for four years. The complex storyline involves a writer (Tony Leung) who projects himself into the year 2046 in order to find his lost love. Wong shot the movie in 2000, right after the release of his highly successful In The Mood For Love. He kept rewriting the script and reshooting sequences for months after until the months became years.

Obviously, this permanent work-in-progress status made 2046 a very unusual project for Buf Compagnie, the French digital studio hired to produce the visual effects. The Parisian company had previously done innovative work for a commercial that Wong had directed. Impressed by the results, the filmmaker had assigned all of the movies 100 effects shots to the studio. 2046 was to be the directors first foray into feature film visual effects and Bufs first Chinese film project ever. For both crews, the prospect of discovering each others culture and sharing work methodologies was one of the most exciting aspects of the project.

2046 marked a real evolution in Wongs directorial style. Until then, he had always shot his movies on sound stages, mostly using tight shots or close-ups, and never employing visual effects. And here was a project that couldnt exist without long panoramic shots and state of the art digital effects! The challenge was more than simply technological for him. It was artistic.

The Shape of Things to Come

The centerpiece of the effects work was the creation of the futuristic city that the main character discovers. Wong wasnt sure what the stylistic approach of these shots should be. Although his art department had produced many sketches and paintings, he asked Buf to come up with suggestions of their own. In order to give the French artists a feel of what he was after, he invited them for a tour of the largest Chinese cities, pointing out architectural styles that he thought could form a basis for his futuristic city. Bufs artists took advantage of this trip to shoot hundreds of reference photographs. Those images were later used to build the distinctive CG city.

Back in Paris, Buf started modeling futuristic buildings by combining architectural elements of real skyscrapers and adding parts that were designed in-house. For modeling, as for the rest of the effects pipeline, the studio relied solely on proprietary software. Textures were either real photographic elements captured on the scouting trip in China or digital creations. Since the artists had been granted complete artistic freedom, they started producing digital cityscapes with wildly different ambiances: sleek or heavily textured, clean or gritty, warm or cold, lively or lifeless. By producing a great variety of looks and ambiances, Buf made sure that Wong could review a maximum of options before nailing down the imagery he was after. In fact, the design process that usually involves the production of many sketches and paintings was tackled on this project mostly in CGI.

From this first series of cityscapes, the director approved several looks that formed the basis for a refined series of tests. These were in turn reviewed and developed into further tests. This lengthy process went on for three years, with every input by Wong being rendered into several CG variations of the concept. Sometimes, the director would send artwork produced by his art department to help clarify specific designs. Little by little, test after test, Buf eventually managed to come up with a unique look that won the directors approval.

A City Unlike Any Other

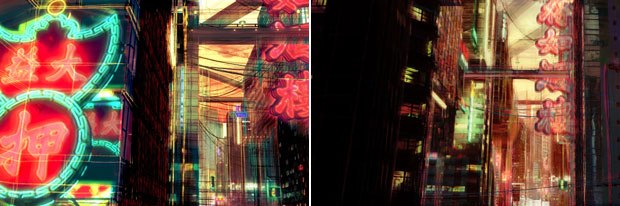

This look took form almost by accident, when Wong once saw a wireframe model of the city. Intrigued by the look of the CG buildings in their most basic form, he asked if the wireframe could somehow be used in the final city imagery. Buf started making tests in which the wireframe element was composited over the final render. The results looked extremely promising. The studio realized that this unprecedented approach could produce a futuristic city unlike any other that had ever been designed for a movie. At the same time, the more Buf explored this option, the more Wong aimed toward a very stylized city.

After months of experimentation, the studio came up with the final look. In each shot of the city, wireframe models of the buildings were colorized and composited over their rendered counterpart, but in order to make it even more intriguing, Buf didnt line them up exactly. Being off mark, the wireframe element gave the cityscape a three-dimensional and surreal look. The wireframe animation was also slightly desynchronized from the main animation, which created the eerie illusion of a vibrating city. The final touch was to lightly bend and twist some wireframe models in ways that made the shots more interesting. Many tests were required for each wireframe effect in order to nail down the spatial and temporal displacements that produced the best results. Again, this process involved generating numerous versions of each shot and just as many revisions before the effects were finally approved.

Even after animation and rendering had been finalized, Wong still had the possibility to tweak the imagery. Buf decided to render most of the layers as individual elements: streetlights, neon lights, cars, pedestrians, but also CG passes. The first advantage was a very short render time; the second was a complete freedom for the director to modify the look of each shot at the compositing stage. Up to the last minute, Wong could create a wide range of ambiances by adjusting the compositing. The final look of the futuristic city is very graphic, highly complex and detailed. It is also surprisingly colored, as the director wanted the digital environments to match the graphic ambiances of the live-action scenes. Many shots feature the characters in stark red settings. Buf matched these ambiances by applying various shades of the same color to the wireframe models. Many different color combinations were submitted to Wong before the right hues and the appropriate balance were nailed down.

All the city shots were entirely computer-generated, sometimes running as long as 40 seconds. Several shots required compositing the environment with actors shot on stage. One sequence features the writer traveling across the city on a futuristic high-speed train. Buf completely designed the bullet-shaped train with only two tips from Wong: the vehicle had to reflect its environment and its architecture should be based on the train system of our time. Therefore, no flying trains in 2046. For shots inside the train in motion, the art department built a train car set in front of a bluescreen. In order to avoid the need of generating blocks of CG buildings, Buf opted for a very stylized environmental look. Since the train was supposed to be traveling at high-speed, this approach worked remarkably well and saved a lot of modeling and rendering time.

Perfecting Effects Integration

Up until a month before the movies September 2004 release, Buf was still modifying architectural models and fine-tuning color balances. Wong wanted the effects shots to truly complement the live-action shots. In his vision, they had to be perfectly integrated into the narrative and aesthetic flow of the movie. As a result, most of the modifications cut implied revisions of the visual effects. Colors, ambiances and dynamics of vfx shots had to be adjusted to match the live-action shots in the same sequences. Since the editing process was spread over several years, the movie remained in production at Buf for three years. Although a lot of work ended up in the trash bin, the studio nonetheless enjoyed the creative process: after handling the movie for such a long period of time, the effects shots were truly well integrated.

One of the unusual aspects of the project was the selection of the movie for the Cannes Festival. Highly regarded by the Festival community, Wong decided to screen a work-in-progress as he was still not satisfied with his final cut. He asked Buf to render temp versions of all the effects shots in order to have a complete print for the screening. These versions were final CG animation shots without the wireframe animation effects added in.

For all involved at Buf, 2046 was a truly unique project: unique in the unprecedented artistic freedom that they enjoyed; unique in the directors approach to the visual effects; and unique in the distinctive style of the digital imagery. For the first time, the studio was actually allowed to express in a feature film the creativity that had become their trademark on commercials. From a visual effects point of view, 2046 was like a commercial produced on a feature film deadline and then some.

Alain Bielik is the founder and special effects editor of renowned effects magazine S.F.X, published in France since 1991. He also contributes to various French publications and occasionally to Cinefex. Hes currently organizing a major special effects exhibition that will open next month in Lyon, France.