Bob Miller drives the road to Madagascar to discover how writer/directors Tom McGrath and Eric Darnell, with animator Jason Schleifer, survived this CG jungle.

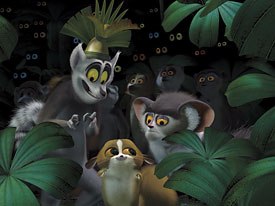

At the Central Park Zoo, Alex the Lion, Marty the Zebra, Gloria the Hippo and Melman the Giraffe are the star attractions. Theyre groomed, well-fed and hundreds of fans adore them. To the four Zoosters, their home is a paradise. But Marty the Zebra is curious. Whats it like outside the zoo? His quest entangles his three friends in a madcap misadventure, which, ultimately, results in their arrival on a remote island. Can four domesticated animals from New York survive in the wild? And when nature rouses their primal instincts, can they survive each other?

Madagascar, the latest animated comedy from DreamWorks, was directed by Eric Darnell and Tom McGrath, and written together with Mark Burton and Billy Frolick. Darnell, who previously directed Antz, relates that production began four-and-a-half years ago, when hand-drawn animated features were still in vogue.

When Madagascar was developed, I dont think it was pitched as any particular medium, he says. That kind of stuff, at least in those days, came out of development as what made the most sense, with the story that we were telling. Once I got involved (my own interest is in CG), it was easy for me to motivate it and steer it in that direction.

Madagascar marks McGraths debut as a feature director. With my background, theres a little bit more to 2D, he says. The CG realm was all new to me. I learned a lot from Eric as well as PDI [Pacific Data Images, officially PDI/DreamWorks]. Eric really wanted to tell the story in a fantasy world that actually was tangible, that you could step into. Thats one of the things that CG can offer. The advancements that PDIs had since Shrek, we were able to take this world, stylize it and actually use the aesthetics of 2D in a 3D world, so you get the best of both worlds.

Regarding CGs technological advancements, Darnell says, People arent working on great pieces of technology unless there is a need. In our case, the creative kind of drove what we did technologically. For example, in the beginning, we could only get four or five furry characters on screen at one time, and we needed 500. So a big effort went in to develop the systems that would allow us to do that. We knew we had a big organic jungle with four million leaves blowing in the wind, and thats finally what we were able to achieve. But no way could we do that four years ago.

Water is always difficult in computer animation, because while nobody quite knows how to make it look right, everybody knows when it looks right. You know when its water. To create a system that would be believable but would also work in the design of the film (its not photorealistic water, either), and also be controllable that we could use it to help tell our story, were huge challenges for the technology folks.

Says McGrath, So many times we were asking, Can we do that? And theyd go, Well get back to you. He chuckles. And then theyd come back and go, Yeah, we can do it. (They would say,) Alex cant touch his mane. In fact, nothing can touch Alexs mane. And we were going, Oh, really? How are we going to stage this? And theyd come back a week later and go, WE CAN TOUCH ALEXS MANE! Wooooooo! We can touch Alexs mane! Theyd go cheering off and wed (exhale sigh of relief).

The other technological challenge was driven by a creative [need], Darnell says. Wed talk about animation style in the film, so we set out from the very beginning this very broad style with squash-and-stretch. But its difficult to do in computer graphics because you basically have a virtual puppet that you have to construct before you begin animation. All the controls and capabilities have to be built into this puppet before you start. With hand-drawn animation, if you want to draw a guy thats normally six feet tall and stretch him out to be 12 feet tall, or flatten him on the ground, you just draw it that way. And youre done. To design a puppet with those kinds of capabilities was a big challenge for us, because we wanted to be able to do that, too. And ultimately can squish our characters to be 12 inches tall or stretch them way out, or have the jaw drop down to the belly button, or when a hand sweeping through the frame, scale it three or four times for a few frames. A lot of times, when you do this, its not something that you see; its something that you feel. Again, these are tricks of the trade that animators have been using for decades, but its that much harder to get into CG. The technical directors that set up these guys have a big challenge with that, too.

I think as a whole our department really started to push smear frames and stretching characters like crazy where it was warranted, says animator Jason Schleifter, who joined DreamWorks after working for WETA on The Lord of the Rings trilogy. We worked really hard to keep the characters on-model when striking a pose, but inbetween poses oh, man, we were going nuts! You'd have fingers stretch five times their normal lengths, eyes bulging all over the place. I even did a shot where a fossa hits the ground and when he does his eyes actually smack into each other, then stretch out so they're 2-1/2 times their normal distance from each other, and then rattle back. It happens so fast it's subtle, but boy does it add a nice punch to the action.

McGrath explains, We wanted to do something, animation-wise, that was more than what youve seen in 3D and to have a 2D sensibility, much like animation in the Forties: Tex Avery, Warner Bros. Because of the advancements we were able to do squash-and-stretch broad animation, and have this in a stylized world thats really believable in 3D.

The world of Madagascar is as caricatured as its characters, which allowed the artists imaginations to run wild.

Says McGrath, There were careful considerations in the design of this world that [production designer] Kendal Cronkite had worked on with the simplification of things, and caricatured. There were no straight angles. Everythings slightly off-skew. We called it Wack Factor. When things got to crazy we pulled it back.

On Antz, when they surfaced the environments, theyd do it with photographs. They would photograph textures and use those. In Madagascar, it was all art. It was all hand-painted designs that were stylized that every surface was treated with. As opposed for using photos, the surfacing was all hand-painted, says McGrath.

The artists in the surfacing department had a blast, says Darnell. Because they could invent every surface, every texture, for the surface of a leaf, the bark of a tree. Everything then could fit into this design paradigm that Kendal and her team devised. They just had a great time. They felt they had a creative input. Whats up there on the screen is theirs.

The majority of the plants that you see in the film are actual plants that are from Madagascar. But theyre also very designed and stylized and fit in the style of the film. Even their organization and arrangement inside the frame and the environment, its very different than how they would occur naturally, as we try to create this stylized fantasy of a jungle based on the Malagasy rain forest.

So for a lot of creatives, it doesnt have to be real. It can be our own version of real, Darnell explains.

For Tom and I, going in, we really encouraged all the leads and frankly everybody who worked on the film to step up and suggest ways we could rethink how we approached these things with different ideas and new solutions that were creative ones, stylistic ones that worked with the flow of the film. Just so we wouldnt get stuck in a rut. We wanted to step out of that. And of course along with that wed give them the responsibility and creative authority to bring those suggestions to fruition as well. Theyre satisfied because they feel theyve had an opportunity to be creative.

Animator Schleifer found that working with the angular designs (created by Craig Kellman, who currently art directs Fosters Home for Imaginary Friends at Cartoon Network) in CG animation was not much of a challenge. I didn't consider it harder or easier. I found it more interesting than working with rounded shapes. You could really strive for those graphic poses with hard angles. It became much more important to pay attention to silhouette, but by paying more attention to it you could end up with some really interesting and funny poses.

As production on Madagascar progressed, and as area studios shut down their commitment to traditional animation, more and more hand-drawn animators transitioned over to the CG realm.

Yeah, there were quite a few traditional (if you want to call them that) 2D animators, McGrath relates. It helped elevate the medium all around, because they learned from guys at CG that have been doing this a long time, and the traditional animators were able to teach those guys in bringing the level up a little bit. Once you think in terms of animation, and you change the medium, the main principles must apply.

A lot of these guys that learned the system came out ahead of the game because they were visualizing their animation, but it was now a new realm, but it was working off the same principles. It really helped us to get the style of animation we wanted as well.

Darnell adds, I think all the animators, too, were surprised at how far we were asking them to push this stuff. Even the guys that knew their stuff on the computer, they were saying, Really? I can really do that? I can really go that far? I can really have them jump six feet in the air and hang there for a second or two before he comes back down? I can really stretch his face that wide? Or on a broad action, scale his hand by a factor of three so it stretches across the screen for a frame? And of course the answer was, Yes. You can. In fact, we kind of dared the animators to go that far. Once they realized what we were going for, stylistically, they couldnt have been happier. It was all a relief for some folks, who have perhaps found that some of the experience in CG was more confining and limiting to the sorts of things that they wished they could do with the medium. So the 2D animators came on board and made it happen. Once they realized what they could get away with it

it spoils them, McGrath says, completing the thought. Im not sure a lot of them would want to go back to naturalism and moving things in a realistic way.

Schleifer agrees wholeheartedly. It was so freeing to be able to try things like that. They really let us use our imagination, and not worry about making something look natural. Need the character to get across from screen right to screen left? Want him to pick up another character? Instead of thinking about how they'd do it naturally, you got to explore fun and weird ways of doing it: What if he jumped up, spun his feet in the air, then caught them on the ground and dragged his hips forward while his chest stayed where it was? Or instead of that, what if he leads with his finger and pulled his whole body across by breaking his knees? If it looked cool and funny, we could do it.

I found that I learned so much about fluidity, and making a movement feel nice instead of focusing on mechanical issues which I had to focus on in the past. If it looked good and felt right, then it was right! What an amazing experience!!

How well did the two directors work together, especially when working in separate locales?

I know that there are those individual directors my hat goes off to them, because theres an incredible amount of decisions to be made on any given day that demanded that the two of us be separate, Darnell says. If we werent, or if there were only one of us, certain parts of production would come to a halt waiting for decisions. And so, having two of us served really well in terms of production.

Darnell, who lives in the San Francisco area, works at PDI/DreamWorks, the north campus. This oftentimes meant conferring with McGrath by VTC, video teleconferencing.

We always joke that wed meet in Bakersfield at Dennys off the freeway, Darnell quips.

McGrath laughs, adding, We both have an enormous amount of frequent flyer miles. Erics family took me in. I became their third adopted child. It was great during the day because the schedule was just minute-to-minute. We had stuff to do. So Id stay at Erics house in San Francisco. We spent many hours on his back porch, getting our ideas together and problem-solving. Or talking with Mireille [Soria, the producer]. So wed get our ducks in a row and work together to problem-solve it, think up new ideas. We really didnt have that much time during the day unless it was at lunch.

According to publicity manager Fumi Kitahara, the crew totaled 246-260 people, with production split between two separate locations. 85% worked at PDI/DreamWorks in Redwood City, California while 15% worked at DreamWorks in Glendale. Most the pre-production and story work was done at the Glendale campus.

You know, its not better than being in one place. Its always better to be [in person], flesh-and-blood to be able to pass somebody in the hallway, or see them at lunch, and say, Hey, you know about that thing, or Hey, I have an idea. Thats a two-way street, of course, as well. To formalize the process a little bit. But, it makes it possible. Without it, you couldnt do it at all. Without it, you couldnt take advantage of some of the wonderful animators that are on different sites, to be able to bring them up together. Thats why its really helped us that weve got this great talent at both locations to be able to mesh and work together.

Schleifer reveals that the animators worked with both directors pretty much equally. I really enjoyed their different views on shots. Both directors would bring something different to the table. Tom had a great way of making you feel like you could really do it. He was extremely supportive as a director, and very open to learning the process. Eric has been doing 3D animation for an incredibly long time, and knew a lot about what we could and couldn't do. I felt like I learned a ton about filmmaking from both of them! Teresa [Cheng, the producer] and Mireille also gave good feedback, and were there to rein things in at times, which was very helpful!

Madagascar was such a blast for me to work on. I felt like I had quite a bit of creative freedom within my shots in Madagascar. One of the things I really appreciated when I first got here was that I was immediately given a broad range of shots to work on, from hero lip-sync to non-hero shots. PDI/DreamWorks really strives to give everyone a chance to have shots they can be proud of which isn't something you find in many studios.

When we started working on some of the newer characters, like Julien [king of the lemurs], Eric and Tom were extremely open to hearing suggestions about ideas for business. You could get a shot handed over to you, and really start to try new ideas: what if Julien tried to emulate Maurice? What if he acts tough, but you can sense this bit of insecurity? I felt like I could really throw ideas in the ring and take ownership of the shots (as long as the fit into what the shot was trying to accomplish, and were in character).

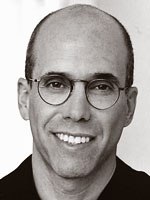

Schleifer credits studio executive Jeffrey Katzenberg as inspirational to the animation crew.

Jeffrey really pushed the idea of going nuts with the animation. He loved some of the wackiness, which was starting to come into the shots, so he really tried to emphasize that side of things. He even offered a prize for the person who animated something so crazy that he'd have to tell us to tone it back. At that point it became incredibly fun to try and come up with new ways of doing things It became incredibly liberating to try new ideas and see when they worked (and when they didn't!).

McGrath concurs. He was like that a lot. He was contributing a lot to the humor as well as the story. I mean, the guys been making films for a really long time, so his notes were valuable to us.

He was a great joke-writer as well. We had Alex at Grand Central Station. Eric and I thought, Hey, why dont we have this old lady beat him with her purse, and Jeffrey would go, Yeah, but you know what? She should kick him in the groin and mace him. And we just all laughed and said, Yeah, lets do that! So he was really great.

Darnell recalls, Theres another similar time where we had the scene where the characters were doing all these spit takes, but we werent just getting the laughs We were getting a lot of advice that this was not a good gag. To Katzenbergs credit, he came in and said, No, the problem is, is you dont have enough. You need two more big spits. And we did that and everybody was cracking up at the screenings. So we thank him for saving the spit-takes.

In traditional animation, lead animators would specialize in a single character, as Glen Keane did as the animation supervisor for Tarzan. According to Schleifer, such was not the case on Madagascar.

The animators would certainly be cast towards their strengths, especially as the end of the film grew closer, he says. We each have different talents, some are better at action shots, others are better at close up drama, others are better at humor. So the directors, animation director and sequence leads would work together to try and cast a sequence so it would be as strong as possible. When they could, they would give us a series of shots in order so we could have a nice continuation, but 99% of the time we would be animating all characters in a single shot.

Madagascar had a sequence where more than one animator worked on the same character in the same scene.

This happened in Sequence 600, Schleifer says, where the Zoosters are caught in a crate on the boat. In this case, because the shot was so long (around 1,400 frames!) they broke up the shot to make it easier. In that one, Cassidy Curtis and David Burgess split Alex (each got 700 frames), Rex Grignon and Denis Cuchon split Marty, Dave Spivack animated Melman and Sean Mahoney animated Gloria.

It happened in a few other sequences as well, but in general they tried to give everyone each character in a shot.

In traditional animated features, sculpted models maquettes are made of each lead character and used as visual reference by the animator. But in a CG film, the characters are already stored in a virtual matrix, always on model for the animator to view from every angle. Are maquettes obsolete in a 3D world?

No, not at all, says Darnell. It was a great way to visualize these guys in 3D without going through all the necessary rigging you have to get a posed character, a character with personality. So it was actually beneficial for us to do that. Once you do get something that you can move around and change the pose on and open the mouth when you want to, and adjust eyebrows, thats when you start to learn about all these things. Its a challenge when you do them in CG, because you start to pose them in different ways and start to find that, Well if I do that, and move this cool clean line thats defining an element of the character, its all twisted and distorted. So how can we maintain that design conceit, and also have it work when we know the animators are going to push these characters all over the place.

Darnell illustrates, In 2D, you can just draw around that. In 3D, if you have a hard line running across the character defining his rib cage or something, that hard line will always be there. Unless you set the rig up that where a character gets pushed into a certain pose, if you wanted to that hard line would be eliminated, or modified, or minimized. Those are the things that you learn when you get these guys into the computer and start moving them around.

On Madagascar, Maquettes were definitely made, and are a great way of translating a 2D drawing into 3D space, says animator Schleifer. The directors can hold them, turn the maquettes, and get a really good idea how light will fall across the surface, whether or not the character's butt or nose are too big, etc. It's a great first step into making the digital 3D models.

Director McGrath concurs, Whats great about maquettes is that before its even in the computer is you can see what its going to be like in three dimensions. Usually theyre pretty rough. But a great deal of computer films is that its still done on paper. Its storyboarded for years. Thats how you work out the film. Theres so many storyboard artists that contribute, that have the maquettes and see the characters, to be able to draw them as well when theyre doing the storyboard. The closer it is to the character, the better sense you have an idea of how visually its working. So theres quite a bit of hand-drawn work behind the CG bells-and-whistles, you know. Theres still quite a bit of artistry

that happens before you take it into the computer, Darnell interjects. Certainly after but certainly before, as well. We also use maquettes a lot just in presenting the film to people when we pitch a story, whether its performers, you can come in and say, This is the character wed like you to play, and spin it around on a Lazy Susan, and its got this great attitude and its right there and its tangible and they can see what it would mean to be that character. So its really valuable in that sense, too. We had some maquettes that were painted up and that looked absolutely beautiful.

For its animation, PDI/DreamWorks uses its own propriety software, Emo, which stands for Emotion.

We use it for moving these characters around and get emotion out of them, Darnell says.

As with traditional animated features, Madagascars cast was videotaped as they recorded their roles, as visual reference for the animators.

At times this would be a big help, Schleifer relates. Most of the time, however, we'd just act the shots out ourselves and try and imagine how the character would be speaking. Sometimes we'd shoot reference of ourselves and other animators acting out shots. Unfortunately, we didn't get to talk to the voice actors at all on Madagascar. While I was animating on The Lord of the Rings, Andy Serkis would come in quite a bit and talk with us about his motivation while performing a scene, which was a real help when dealing with the multiple levels of insanity that Gollum had!

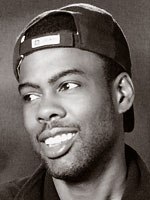

Notably, Madagascars characters are voiced by talents best known for their live-action work, with Ben Stiller as Alex the Lion, Chris Rock as Marty the Zebra, David Schwimmer as Melman the Giraffe and Jada Pinkett Smith as Gloria the Hippo. For a character to be believable in animation, the performer has to be able to convey personality through the vocal performance, alone. Were these live-action celebrities up to the task, or were they hired solely for marquee value?

Darnell responds, You know, theyre great actors, whether theyre on camera or whether theyre in front of a microphone, which is why we go to them. Its really, for us, finding the right character the right voice to match the character. In this movie, it was even more of a challenge because of the ensemble nature, to find voices that play off of each other nicely, so, we would actually cut material together from other films that these guys had done, even though it was nonsense, but, cut it together as if they were having a conversation, just so we could hear how Jada bounced against Chris, against David, against Ben, and get a feeling for how they might mesh. It ended working out really well.

McGrath adds, You try not to put anyone in a position where they would suck, by the way we cast. If you think of an actor, its easier to look at them and see a performance come through. We dont look at them at all. We listen to them. As Eric was saying, thats how we really cast. We listen to the voices, and you can tell if theyll be a good animated voice character.

However, for recording sessions, the actors did not record their lines as an ensemble.

We always recorded individually, Darnell says. That way we could stay focused on getting the performance. These guys are all famous, talented comedic actors. Even if we wanted to get them into the same room at the same time, its almost impossible because theyre so busy. So you dont want to depend upon that, certainly.

Its always nice to be able to focus on just one person at a time. Its a very exhausting process doing a vocal recording because the actor has to imagine everything and put themselves in [the characters] place, that doesnt exist. It takes a lot of brainpower to do that. And the performance moving from sequence to sequence to sequence takes a great deal of energy. Ultimately, it worked out really well because they would do some stuff, try out some things. We can take them back to our animation wonderland and push and pull things around while things are playing, and the following week wed record another actor whose voice might be alongside the first one, and get the leverage off of what theyd done, and their ideas and what they infused into the performance. The second actor comes in and adds their own component and wed go back to the first actor a few weeks later and its a very collaborate process. Over the course of a few years wed go in and bring in one of these comedic voices maybe ten, fifteen times. Each time they would rework what theyd done before, trying out new sequences that werent ready yet. Its very, very cyclic in that way. It allows us to make the movie so much better because when you can throw out some things that dont work.

McGrath notes that, The high point for them is to having to go Ow! Ooo Ahh! and do all these efforts over and over. OK, youre falling down a hill and you hit rocks. Then you hit cactus, and now you hit flowers. A lot of it is doing all these vocal efforts that sound ridiculous. Its funny, when you go in and one of your last lines is, youre stepping on a thorn. You just have to get this. And theyd come in and theyd do it. Its kind of an interesting process I would think from an actors point of view. As Eric was saying, its all coming from the imagination in a pretend world.

The directors found that having comedians in the cast was advantageous, as they improvised lines during recording sessions.

Says Darnell, Tom and I dont write lines like, This place is crackalacka. Thats pure Chris Rock. And we encourage a lot of improvisation and adlibbing in the studio. You know. We will get whats on the page, and ask the guys, How would you say this? How would you respond if Marty came at you with this question? And so we encourage it.

Our process allows us to take advantage of that. We spent two years working on story and recording the voice talent before we animate a single frame of the final film.

[Our actors] make up this stuff and its gold for us, McGrath says, then notes ruefully, At some point its tough, but you have to cut some of this stuff down. Its heartbreaking, in a way.

Not all the roles were performed by celebrities. Some voices came from the production team itself. For example, McGrath voiced Skipper, the lead penguin. Chris Miller (not relation to the author of this report), head of story on Shrek 2, voiced another penguin, Kowalski. Audiences also heard him as the Magic Mirror in the Shrek films, and the Tower Guard in Sinbad. Chris Knights, assistant editor on the Shrek films and Madagascar, voiced another penguin, Private (and one of Shreks Three Blind Mice). And the voice of Mason the monkey comes from CalArts graduate Conrad Vernon, co-director of Shrek 2 and voice of the Gingerbread Man, Cedric, the Muffin Man, Mongo and the Announcer. He also composed the song Merry Men in Shrek.

Madagascar sees nationwide release on May 27, 2005. With the film rating high with pre-release focus groups, and as a potential franchise for DreamWorks, is a sequel in the works?

McGrath replies, Weve thought of that possibility, since weve been working with these characters for about four years. If by some luck (knock on wood) the film does well, there might be a possibility of it. We havent planned it, but as far as Eric and I thinking, What else can these guys get into?

Says Darnell, Everybody says the film seems to end with this feeling that theres a sequel on the way. He laughs. We struggled to not do that. For us, what we wanted to say at the end of the film was this theme that became the foundation of the movie, which is its not where you are, but who youre with. Ultimately, in our minds, it doesnt matter where the Zoosters end up in this story.

Theyre all content, McGrath says. [Suddenly] Hey, lets pull the rug out from under them, just as a joke.

Just for a joke at the end, Darnell says. Yeah.

There is a mystique with animation and how its done, McGrath observes. In fact its very similar to the same kind of problems in a live-action film. The biggest consideration as a director is we have to concentrate on the story and characters. Thats with any film, regardless of what medium. Story is the most important thing. Everything else branches out from that.

Ultimately, everything that youre doing has to serve the story, says Darnell. And also what Tom has said, the biggest difference [between live action and animation] is for every single pixel, every square inch of that screen, somebody has to make a decision about what youre looking at. Tom and I are not only making big decisions about story and script, but also, what color is the bark on that tree? And what is the groundcover? Are there a lot of sticks on the ground or is there grass? Are there leaves on the ground? How many leaves do you want? When characters go through this environment, do the leaves get kicked up? Or can they just stay on the ground? When they go past a bush, do you want the bush to move? Theres all these things [to consider]. Cause nothing is for free.

Says McGrath, The exciting part, for us, is to actually start with an idea, and then see it through and see it up on the screens, to see how people react to it. Thats what its all about. Thats the fun of it, when you finally get to see it in the theater with the big crowd and watch it and go, Wow, we did it! We made it!

Since 1985 Bob Miller has written numerous articles covering the animation industry for publications such as Starlog, Comics Scene, Comics Buyers Guide, Animation Magazine, Animato! and Animation World Magazine. He was storyboard supervisor for MGMs Lionhearts, Courage the Cowardly Dog for Stretch Films/Cartoon Network, Megas XLR for Cartoon Network, and lately, the Say it with Noddy 3D interstitials for Make Room for Noddy, coming this summer to PBS Kids. Bob won a 1999-2000 primetime Emmy Award certificate for storyboarding on The Simpsons episode, Behind the Laughter. Bob serves on the board of directors at the International Animated Film Society, ASIFA-Hollywood.