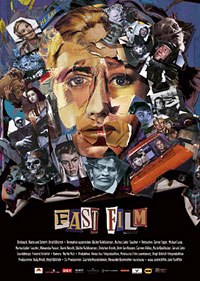

Chris J. Robinson looks into how Virgil Widrich was inspired and how he produced his new innovative short piece, Fast Film.

With few exceptions, there havent been many films on the animation festival circuit over the last year that tickled me. One of those that did though was a technological and conceptual dandy from Austria called Fast Film.

On the surface, the plot is a bit been there, done that. A man and woman kiss. The woman is imprisoned in some Doug Henning-like trunk and taken away. The man follows after her via horse, train, car and plane. He finally locates her in the villains underground lair. The duo flees from the lair and survives a dramatic airplane chase/shootout, before finally reaching safety where they end as they began: with a kiss.

The storyline in Fast Film may be facile, but the technique Widrich employs and the overall effect of the movie is unique.

OK so yeah, its not all that impressive a story. Seen that three or 36 times before. But remember that wacky Luis Buñuel film, That Obscure Object of Desire, where he had one character played by two actresses? Well, in Fast Film, the hero, heroine and villains are portrayed by different actors every 5-10 seconds. The hero is played at various points by Gene Kelly, Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grantx2 (young and old), Buster Keaton, Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Sean Connery and even Rod Taylor. The woman shifts from Lauren Bacall and Mary Astor to Eve Marie Saint, Grace Kelly, Vera Miles, and my favorite old hottie, Cyd Charisse. And the villains include Vincent Price, James Mason, Dr. Strangelove, Frankenstein, Godzilla, John Garfield and the creature from the Black Lagoon.

Still not impressed? Well, how about that this 14-minute short is composed of more than 65,000 paper printouts of individual images from 400+ live-action films (including Maltese Falcon, The Bandwagon, Videodrome, Psycho, North By Northwest, Godzilla, The General, Dr. Strangelove, Raiders of the Lost Ark, To Catch a Thief, Breathless and a variety of Sean Connery era Jimmy Bond performances). Director Virgil Widrich and his production team took the paper printouts and folded them into a variety of objects including train cars, planes (e.g. a photograph of John Wayne as a fighter pilot is folded into a paper airplane), landscapes and a clever little wheel of fortune torture device that mix and matches heads with body parts. (The best one features the head of James Woods with a body comprised solely of a hand flicking a lighter.) The printout landscapes and scenarios were photographed using a Canon EOS D30 digital still camera with 2,048x1,536 pixel resolution and then loaded into the computer one image at a time. Adobe After Effects was the most technical tool used in the process in addition to the computer hard drive.

Now are you impressed? Thought so.

Widrich got the idea for Fast Film while finishing his last film, Copy Shop. As he says during an interview from a short Making of Fast Film documentary, While in the studio we tore up lots of paper for the films [Copy Shop] sound effects. By that evening the floor was covered with all the images from Copy Shop. And then I noticed that there was this man walking in some of them. So there were these objects on the ground with a walking man and I suddenly thought that it could be made into a film.

Fast Film took two-and-a-half years to create with almost a year of that devoted solely to folding and animating. The complexity of the film also required a strict but supple system: We digitized 1,200 scenes from film, says Widrich, and kept an extensive database with titles, keywords, image description etc. to be as fast as possible whenever we needed a certain shot. (Ah... where was that shot with the hand holding a gun in black-and-white?) Then we had 65,000 physical objects to sort and store and really millions of files of all the versions of all the shots and all the objects. So keeping pedantic order was essential to stay flexible.

Remarkably the film was made for only 100,000. It was very small, notes Widrich, and the film could only be made with a very enthusiastic crew. Some of them had a day job and worked for Fast Film in the night. Me, too.

At least three different images are used in background, foreground and action of every scene. The most complex and elaborate scene was the train crash sequence. About 30 layers of images were used for this scene which shows five trains (with cars attached) racing along the tracks and over a cliff. So we had movement of the trains, films in each locomotive and car, and the camera (and a zillion reflections in the rotation to kill) said Widrich. Widrich and his crew spent almost six months dealing with the challenges of this single scene.

But Fast Film is more than just another one of tech-fetish films. The technology is certainly fascinating in itself, but its uniqueness and complexity also injects the narrative/plot/story with a medley of critical readings. Each screening undresses a new identity. You can follow the paint-by-numbers plot, enjoy the film as a tour of film history or dive in a little deeper and explore the film as a clever little self-reflexive text that ferociously criticizes the sweeping sameness of Hollywood cinema.

The fact that 400 films and an assortment of interchangeable actors can all be compressed with relative ease and believability into a single short film says a lot about the shortcomings of classical narrative cinema. Or maybe Fast Film is about the future of animation. Is Fast Film animations resistance against the fear of digital domination? Does Fast Film assimilate photorealistic images and digital technologies into an animation world? Or is animation the medium being devoured once and for all?

Whatever your take, Fast Film is a clever, cool, happy-go-schizoid cross between Marv Newlands Anijam, George Griffins Viewmaster, Frank Mouris Frank Film, Thats Entertainment 1, 2 and 3, Film Studies 101, Walter Benjamin, and my cousin, Edna; a rare piece of animation that transgresses the often hoarding and myopic borders of animations hermits. Fast Film is more than animation; its the you-best-be-seeing-this moving picture of the moment.

Go buy it now at www.widrichfilm.com/fastfilm.

Chris J. Robinson is the artistic director of the Ottawa International Animation Festival and the Ottawa International Student Animation Festival. He is also the editor of the semi-annual ASIFA Magazine. His book Between Genius and Utter Illiteracy: A Story of Estonian Animation will be published in May. He is working on a strange book about childhood, alcoholism and an ex-hockey player tentatively called The Boy Who Never Grew Up.