Melissa Chimovitz interviews Polish independent animators Jerzy Kucia and Piotr Dumala, with the help of oTTo Alder, at the Fantoche Film Festival.

Download a Quicktime movie from Piotr Dumala's Lycantrophy. © Piotr Dumala. 693KB.

September 11, 1997 Fantoche Animation Festival, Baden, Switzerland

If one were asked to characterize Polish animation, it would be a true challenge to identify in words that slippery thing that makes Polish films so distinctively Polish. Perhaps this is because the only thing that all animators of that origin have in common (besides their nationality) is the singularity of their own vision and the integrity of their individual styles. Or perhaps it is because to try to describe in words the work of many Polish animators would be a misdeed, since feelings, not words, are many of these artists' primary motivation. Certainly this is the case for two contemporary animators, Jerzy Kucia and Piotr Dumala. Although vastly different in both their stylistic and thematic approaches to animation, these filmmakers do share that nearly unnamable attribute that creates a mood and an atmosphere unique to Polish animation.

Profile: Jerzy Kucia

Jerzy Kucia (b.1942) was trained as a painter and graphic artist at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, where he is currently a professor and the head of the animation department. His first animated film, Return, was completed in 1972, and demonstrates beautifully Kucia's interest in the interplay between reality, memory, dream, and emotion. In Return, although we are observing a rather static, uneventful moment in one man's life (throughout most of the film, we watch him looking out the window of a train as a country landscape rushes by), it is clear that the real action is taking place within the man's (and our own) mental landscape. The regular and rhythmic sound of the moving train, together with the hypnotic night-time scenery sweeping by, enables the viewer to slip into his or her own dreamlike journey. In the 25 years since his first film, Kucia has revisited this motif and perfected his unique visual language in eight more films, all but one of which utilize a very similar abstract structure to present their themes. The one exception is Reflections (1979), which is Kucia's only film to date that attempts to follow a narrative in the classic sense. Reflections, also about a journey of sorts, follows the laborious struggle of an insect hatching from its cocoon. No sooner than the insect wrests itself from its shell does it become involved in a life struggle with another insect. The drama ends abruptly when both bugs are crushed under a man's shoe. Bleak though the message may be, Kucia manages to draw us once again into a singular, almost microscopic moment of time that is at once dreamlike and poetic, yet grounded in grim reality. Kucia's most recent film, Across the Field (1992), is his longest and arguably his most complex film in terms of imagery. In it, he applies many of the various techniques he has developed for his films over the years, the result being a rich collage of drawing, photographic images, and live-action film footage whose individual frames he has manipulated. This complex technique exists, according to Kucia, only as a vehicle to evoke the mood and emotion he wishes the audience to experience. This Impressionist approach to filmmaking is no doubt what inspired Marcin Gizycki to dub Kucia the "Bresson of Polish animated film."

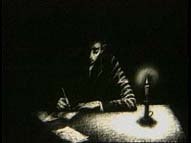

Profile: Piotr Dumala

The films of Piotr Dumala, though much more straightforward in their approach to storytelling than Kucia's, also leave the audience with a strong sense of mood and emotion. Even his more comic films, like Little Black Riding Hood (a twisted adaptation of the classic fairy tale in which the display of bloodlust on the part of the protagonist and a brief moment of inter-species copulation make it worthy of an R rating) leave the viewer with a sense that there is something dark and unexplainable within human nature. Here once again the artist's unique technical developments are responsible for the film's evocative mood. Like Kucia, Dumala works primarily in black and white. Oddly, he stumbled upon his animation technique while studying sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. While working with plaster in his studio, he found that if he painted and then scratched into a block of plaster with sharp tools, he had a surface that he could add to and subtract from to make his drawings appear to move under the camera. The mood of Dumala's films can vary according to the quality of his mark-making; his line quality ranges from high-contrast, bold, scratchy and energetic to soft, dreamlike, and rendered. Although Dumala claims that his films are not political, two of his early films, Lycantrophy and Walls stand out as profound commentary on life in a totalitarian environment. In Walls, a tiny man trapped and routinely observed within a small box responds to his situation at first with fear, madness, and finally lethargy. Lycantrophy opens with a pack of hungry wolves chasing a man across a barren landscape. After catching and devouring him, the pack rests contentedly until one of the wolves pulls off his head to reveal that he is a man in a wolf suit. The pack, eyeing him hungrily, turns against him and he soon meets the same fate as the original man. This cycle continues until it is evident that all of the wolves are really men in wolf suits, a clever way of presenting the innate contradictions and dangers of a totalitarian system. Dumala's more recent work borrows from the surreal and fantastic elements of 20th century Eastern European literature. Freedom of the Leg and Franz Kafka are very much influenced by the writings of Nikolai Gogol and, of course, Franz Kafka. Currently, though, Dumala is at work adapting a piece from his favorite author, Dostoyevsky. Crime and Punishment, his most ambitious project yet, will no doubt incorporate the poetic imagery and evocative mood that Dumala has mastered in his previous work. A Meeting of the Minds Piotr Dumala and Jerzy Kucia met and became friends many years ago at an international animation festival, but say that despite the fact that they live in the same country, they only see each other at the festivals. At September's Fantoche Animation Festival in Baden, Switzerland, where both of their complete works were being shown in a retrospective, I had the distinct honor of meeting them and interviewing them together for the first time. Joining us for a light lunch and heavy questions were Fantoche director oTTo Alder and Ron Diamond of Animation World Magazine. Melissa Chimovitz: I have decided that because this interview is not only an interview, but a meal as well, that we would have a light course of questions to start - the `appetizer' questions, then move on to the meatier, main course-kind of questions... Piotr Dumala: Maybe some drinks, after? MC: Sure. Some digestif questions, perhaps? We'll see You have both found your way to animation through different media. Piotr, you have a sculpture background, and Jerzy, you were a graphic artist and a painter. I'm wondering what led you to animation? Jerzy, you have even said that you are a filmmaker "by chance"

Jerzy Kucia: Yes, it really was by chance. I didn't want to be a filmmaker. I wanted to be a painter, and I studied as a painter and a graphic artist. I made a short [film] exercise when I was a student, and I thought that it was not for me. After a few months I noticed that I needed movement to talk about reality, to talk about my friends, about my situation in Poland. It was easier to talk about reality using movement. So it was by chance in that way that I became a filmmaker. PD: In my case it was a bit different because I think I always wanted to make animation from the first time I saw some film on the TV. I was a kid, and I loved it from the first moment. MC: Do you remember what it was? PD: I don't remember. It was probably Disney, but I loved just films in general, not only animation. The second thing that was important was that I always liked to tell stories. So for me, animation is my way to tell stories, with drawings and movement together. MC: What can animation accomplish that these other mediums that you've already worked in cannot? PD: There is a magical moment when you see your work in movement. You expect something, but you are not able to predict everything. When I see my film on the screen for the first time, there is always something that surprises me, and I very much like it. MC: Even now, after you've been making films for 15 years?

PD: Yes, even more than before, in a different way, but it's a very strong feeling when I see it. JK: The animation process is important because I can create everything. My inspiration is from reality, but it is the process of creation that is for me very important now. Maybe not in the future, maybe not in the past, but at this moment, it's very important. oTTo Alder: Jerzy, do you understand yourself as an animation artist, or do you think of your work as filmmaking, that it's more than animation? JK: It is the same. I don't see the difference between film and animation. It is a problem only of what elements I will choose to use. PD: For me, I know that there is something I want to show. It doesn't matter which way I do it. But animation is the best way to show my private, interior world. It is the way to discover my dreams, my desire, all my feelings. I can show this through animation because it is connected with drawing. I have no idea about using a live-action camera, so my way of telling stories is to create everything, like Jerzy said. I like also this moment of [total] creation. With animation, this is possible. OA: Do you see a pure technical difference between live-action, video, or documentary on one side and animation on the other? Because if you shoot a documentary or a live-action, you shoot with 24 frames per second, but if you are an animator, you have access to every single frame. You have power over the single frame, and the material you use and the technique you use - it's different from reality . Filmmaking, this 24 frames per second, it's a totally different technique. JK: Yes, I agree with you. I see the difference between animation, live-action, and documentary, but when I am making an animated film or a documentary, I am a filmmaker too. But I see a big difference, of course. PD: But in a way, you are closer to documentary film than I am. You use in your animation real things, real sequences - JK: Maybe this is so, but I think that is just a characteristic of my work. It's documentary sometimes, and it's animation sometimes. PD: In my case, also, I can say it's documentary, but documentary of my interior.

MC: How does it feel to see all of your films in retrospective? Does it cause you to reflect on the changes that have taken place in your work from your first film to the present? JK: I don't like to see my retrospective! From time to time, when I look at the films, I would like to change everything. During the projection, I am even thinking about how to change the soundtrack! It is not interesting to see my films again. Maybe it is more interesting for [the audience], but not for me. Right now, I am preparing a new film, so I am thinking about the new film, not the last film.

PD: It depends upon my mood. Sometimes I see my films again and again, not because of a retrospective, but because I show it to my friends at home, etc. In those cases, I don't like it very much. I feel a bit ashamed. But it's different when I see them with a big group of people, because I feel how people can appreciate [the films], what feelings they cause. I like to feel again that these films are still alive, that they have some energy. Also, I am very concentrated on the past: my past and the past in general. So, it's interesting for me to see the whole process - the whole 15 years since I started doing animation as one whole passage, and to see how I've changed. MC: Do the changes in your filmmaking correspond to the changes in Poland? The social changes and political changes? JK: Yes, for me that was very important. It was changing reality. I was talking about common life. It is my basic problem. My basic problem isn't fashion or style, only reality. And I had this problem last time when everything in Poland was changing. Now I would like to talk about the new situation. I am not talking about social problems, but I am talking about friends, and about people, and about their situation, and about my situation, too. I'm one of these people, and because of this, the situation in Poland is very important. PD: Me, I am different. I'm quite far from the political and social situation in Poland. I don't feel like a participant of the society. Of course, I have to a little, it's not possible to not [be a part of it], but it's not the point of my interest. I'd rather show my own things, my own feelings. Then, later, I can see how the films which I made in that time are connected to the situation in Poland. MC: Lycantrophy, for example.... PD: Yes, some people have told me that Lycantrophy is a very strong film against the Communist system. I was never conscious about it, but now I can say yes, maybe.

OA: I have two questions. I realize that it's my personal point of view, but would you agree when I point out that a good animation artist, for example, Caroline Leaf, Yuri Norstein, Norman McLaren or both of you, develop three things: his own technique, his own style, and his own way of storytelling? JK: It is the film language that I am using that is important, because if you want to talk about everything, you must find the way to show your problems. Because of that, you must have your own language. Of course, this language could change. Maybe in my next film, my language will be different, but it was very important to find my own language. For me, technique is totally unimportant because I am telling my problems, maybe not stories, but problems, and technique only helps me. OA: But your technique is quite unique! I can recognize Jerzy Kucia's way of telling stories, and it is very different from Piotr Dumala's way, or Caroline Leaf's JK: Yes, yes, I agree with you, but language and the visual side must be recognized. Most important is how I can find a very simple way to show this problem. I am always looking for an easy technique, but always it is very difficult. Language for me is most important, to look for this contact with others. For me a reel of film is not only film, it is this interaction with the inside of the audience.

PD: Each of us finds our own language. I feel lucky that I found it. I feel it is a part of myself, this language I use. I like to work, because I like these tools. I like this style. This is important, of course... I am very close to such things like religion, psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, etc., so my language is very close to these things. It's close to the language of dreams, and of symbols, and universal things. This is the most important problem. In this way, I am not so close to the [social and political] situation [in Poland] because I don't want to make any references to the situation. If it is there, it is not because I want it, but it happened. I am just like an instrument, just playing what I want to play, and then I am surprised by what I see. Of course, it is not so much completely improvisation, but a big part of it is. This language I like is a very deep language of symbols, of things from dreams. I think Jerzy is similar, but in a different way. His is also a language of symbols. MC: I think you are similar in that you both deal with dream and reality. You both use your films as a vehicle to express your dreams, as well as your realities. PD: I agree. OA: Thomas Basgier once said that `animation is the link between dream and reality.' Do you agree? JK: Yes, and it even depends on the experience of the audience. But that is a good way to say it, yes. OA: I have a special question for you, Jerzy, because you try to take your work out of the usual distribution system. It's very difficult to get a film on video from Jerzy Kucia. I'm sure people offer to distribute your films, but it's very difficult to get a video copy. It is also difficult to get your prints. Can you tell me, is it a kind of artistic policy to make the viewings of your work very rare? Is it a kind of strategic move?

MC: I've heard you say that it should be like a holiday to see your films... JK: Yes, because it is impossible to see my films every morning , it is not a good way. PD: (Laughing) Only every week... JK: (Laughs) It is better every night! (All laugh) But people must want to see them, and I would like to make films that people want to see several times, not once only. On several occasions, but not every morning. OA: You're doing an interview for Animation World Network, so that's a new media, the Internet. What is your relationship with this new media? You're both still working with this - how would you call it? - "old technique," with this material, film; you can feel it, you can scratch on it, it has this material feeling. How about this new virtual media? What is your relation to this new explosion? JK: I think it is very interesting. I would like to make [films for the Internet]. Not today, but in the future, I must be ready to do it. I've even started because I've made a short film for the Internet [for the Absolut Panushka Online Animation Festival] but I would like to make films for the Internet. It must be different than I've made before. PD: I agree with Jerzy, that it must be something different if I do this in the future. [The film] should be completely different than what I do now. Of course, I think also about something which could work together, [like] laser disc [CD-ROM] could be just as good a place to create instead of [using] film. But I'm not sure if I will keep doing films. So if I keep doing it, I will stay with film. It's traditional.

MC: Do you consider doing something else? PD: I think sometimes when I do a drawing in my film, I want to keep it, but I must destroy it because this is the technique I use. I must destroy every frame to put in its place another one, the next one, to have movement. This way, sometimes I think it is too much suffering, to destroy all the time what I am doing. I would like to do some paintings, some graphic drawings, sculpture, writing.

MC: Is film not immortal enough? PD: No, I don't mean that. I mean film, like Jerzy said, is a process. I love that it is a process. It is only a piece of time - when I work, and then when I see it. I am concentrated on movement in general, movement of personality, and everything. Maybe it is kind of a philosophical thing. When movement seems so strong, when I feel the movement so well in general, and [I will feel] a part of the movement, then maybe I will stop making film because I will be film. It is difficult to explain.

OA: Twenty years ago there were about maybe two or three festivals just for animation. Meanwhile, we have a growing number of festivals. What does it mean for you as artists? Is it a better situation now for the artists, or are you critical of this [phenomenon] that there are festivals in each country? JK: It is not easy to answer, because of course, for animation, I think it is good that there are a lot of different events. But I don't like [that] some of the festivals became markets, not a show of art. Mainly I am talking about the big festivals, and for me these festivals are not interesting. They are good for my job as a market, but there is a big difference between a market and a film festival. Animation is a very large art, and we have a lot of problems to show. We need more markets, but in markets, not in market-like film festivals. PD: I feel the same, that there are two different tasks of the festival. Some festivals are good because of advertising, and to make people interested in selling films, buying films. But some festivals, like this one (Fantoche), are more for the artists themselves. They are good as inspiration, as a point of meeting other people. So we need both of them, yes. MC: What are some of the new obstacles that you face as an animator after the fall of Communism in Poland? JK: Ah, it is not only my problem, it is a problem for every artist, every filmmaker probably in Poland. My problem was that I couldn't find my way to a new situation. First, I must tell you that I work from reality: from Polish situation, from Polish tradition, from traditional Polish art. The new situation change was interesting for me, but I couldn't find the answer to this very complicated situation. It is an emotional situation, it is about people who live in the same time as me. But it is difficult for me to find the moments I could show. It is difficult for me to answer in words, but I would like to answer in my next film (laughs). PD: Yes, as Jerzy said, it's an emotional situation. One problem is economical. How to make films, where to get money, etc. This may be a bigger problem not for us, but for students, for younger people who start. Another problem is mental, or emotional: do people still need art or not? Where is animation now? Because before, it was a kind of way to say that we don't agree, or that we have our own private world, or something like this. But now, in this time of bigger freedom and when people have different aims, like money, like making their life better than before, where is the place for art, for culture? This is not in balance now. So maybe this a bigger problem than money. MC: You describe it as a problem in terms of audience, but is it a problem for you? You've already said that you don't make films for political reasons, but do you find that you have nothing now to push against?

"The animation process is important because I can create everything." - Jerzy Kucia.

PD: I've adapted quite well. I made many more films during the last five years than during the previous ten years. Now I'm doing at last, the film of my dreams which I've wanted to make since I graduated from school when I was 22. MC: Which is....? PD: Crime and Punishment. So, I'm lucky with what happened. I'm still doing films, still doing what I want, but I think it's more difficult for young people.

MC: Jerzy, do you feel the same way? JK: Yes, the time in Poland during the last few years has been very interesting. Everything was changing: mentality, economically, everything. It was very interesting to see this, but it really was very difficult to start production. With the young filmmakers, I spend a lot of time to help them because I'm a teacher, and we organized an International Workshop (The Krakow Animated Film Workshop). It was a very important problem, how to push young people, how to push their ideas. It was one generation who couldn't just start. But now I think they are better, some of them, not everyone, because they had to make this first step. I don't want to be a producer! But it was the best way to continue my work as an artist, so I do it. I learned how to be a producer, so now it's okay. But as I told you, for young people, it is not easy, but it is the future for them. MC: That's true. You two have had to learn to adapt and survive, but you had something to fall back on, which was your previous career. Whereas, for new people coming in, it's almost as though they're starting from the same point where most young filmmakers are starting out. They have to face these obstacles the same way everyone else does. They have to find the money, struggle, etc... PD: Yes, that's true. Before, it was obvious. When I started, I just came to the studio, and they had money, and they gave me money for my first, second and third film. MC: Were you limited in any way, then, in terms of your expression, due to their sponsorship? PD: No, not very much. Just if there were some personal things, but never with political issues. But I think that these young student filmmakers are different people than I was. So, I hope they will manage, because during their study, they learn how to be independent, and how to help themselves. They are probably better prepared to be filmmakers in this situation than I was. JK: Their situation could even be better than ours was because they have more possibilities than we had. PD: They go abroad. They see more films. They see more paintings. They can learn languages. We could, but with special pressure; we had to.

want to play, and then I am surprised by what I see." - Piotr Dumala. Photo courtesy of and © Krzysztof Miller.

(Laughing) PD: Me too! JK: I might not want to make the same films... (All laugh) MC: Interesting! That's not the answer I expected. What is the primary advice that you offer [your students]? JK: To try to recognize their film's personality. I would like to push their personality. It is my most important lesson because they must find their own way. Of course, to learn how to animate, how to shoot the film is very easy, but how to develop the art is the most important thing. JK: To try to recognize their film's personality. I would like to push their personality. It is my most important lesson because they must find their own way. Of course, to learn how to animate, how to shoot the film is very easy, but how to develop the art is the most important thing. Visit the Animation World Network Vault to view the complete filmographies of Jerzy Kucia and Piotr Dumala. Melissa Chimovitz is a freelance writer with a predilection towards run-on-sentences. Armed with a degree in photography from Rhode Island School of Design, a portfolio of handmade puppets, a short animated film ( Eat'm Up: A Very Short Film About Love [1997]), and a determination to become a great animator, she will enter Cal Arts' Masters Program for Experimental Animation in September 1998. In the meantime, she lives happily in Brooklyn, New York, where she is participating in Janie Geiser's soon-to-be-named puppetry lab and working on a new film.