MainBrain's Tom Mason (Dinosaurs For Hire), Steve Rude (Nexus) and Randy and Jean-Marc Lofficier (The Garage) describe their experiences in the world of development.

Scores of people on any given day are waiting for that call, that go-ahead, that "Yes, we want to put your property into development!" But what happens next? How many don't end up on television or in theaters? How many do but take years to happen? How many still have creators involved that are happy they got the call in the first place? We asked some of the leading comic creators and agents who are working toward developing their books into animated shows, "What was your experience when your comic book was made into or was going to be made into an animated product? What do you wish you had known beforehand?"

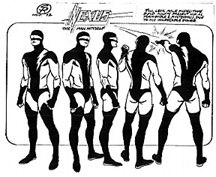

Steve Rude

Steve Rude created Nexus with writer Mike Baron in 1981. Initially published by Capital City, it became one of the first color titles from First Comics in 1985. Steve has worked for DC on such projects as Space Ghost, Mister Miracle and has recently done the art and covers for three issues of the World's Finest series. Dark Horse is now publishing Nexus and Steve has been working on converting the property into an animated series for several years.

"My first direct hit with Nexus as an animated show came in August 1993, when I met Fred Seibert from Hanna-Barbera. Fred was the new President of the same company that founded many of my favorite cartoon shows, and so having Nexus there seemed appropriate. Introduced through a mutual friend at the San Diego Comic Con, Fred and I hit it off right away. Later, I would introduce Fred to the work that friends and I had thus far put into making Nexus an on screen reality.

The deal at Hanna-Barbera took forever to make, and I got my first real dose of the legal end of deal making, and the glacial pace at which lawyers work. Eight months later we reached a deal. No one had ever been able to properly explain to me why this legal process must take so long. It was an exercise in boredom and frustration.

Working with Joy Every, the Vice-President of Hanna-Barbera's feature animation development department, we were able to secure the talents of Eric Luke, a seasoned script writer and fellow Nexus fan. The story outline he turned out for Nexus was fantastic. But, with recent changes in corporate personnel, we were subjected to an endless period of inactivity, and soon found ourselves back to where we started. It was, however, in Joy's contract that she be permitted to take Nexus elsewhere. So, for the next year, she, I, and Eric tried to interest other studios in Nexus. After countless pitch meetings at places big and small, we were turned down by each and every one of them.

Joy eventually moved on to greener pastures, and I, one Steve Rude, found himself sitting back at the all-too-familiar square one. Undaunted, however, and knowing, absolutely knowing, that someone would eventually soon see the light, I made contact with Joe Pearson at Epoch where it is presently awaiting sale. Joe was my second choice after Rough Draft, the company responsible for the brilliant Maxx series for MTV, turned it down.

Along the way, I picked up a new agent, Jean-Marc Lofficier, and couldn't be happier. The man listens and understands. He also promptly returns my phone calls. Three things to look for in a lawyer.

Bottom line -- Trust your instincts and develop the courage to see them through. If a deal smells bad, don't do it. If you follow through with people you don't trust, get ready for your worst nightmare.

Finally, remember that the entertainment industry's greatest triumphs were routinely turned down by dozens of studios before breaking through. Don't give up!"

Tom Mason, MainBrain Productions

Tom Mason is a partner in MainBrain Productions, the Malibu, California-based entertainment development company whose clients include Universal Studios, Klasky Csupo, Gunther-Wahl, Morgan Creek, and Dreamworks SKG. He once took an unforgettable holiday in "Development Hell" with a comic book he created called "Dinosaurs For Hire."

"Let's say 'the call' finally came and now somebody wants to take your comic book -- your precious jewel, your baby -- and turn it into the next big Saturday morning blockbuster, assuming they still show cartoons on Saturday morning by the time you finish production. 'Oh boy!' is one of the more printable exclamations you'll yell after you hang up the phone.

The next step is the negotiation. When you're sitting in the conference room filled with people in tailored suits whose beautiful assistants are offering you chilled Evian and platefuls of spiced ham, and you're shaking hands with people whose names you've seen on your television screen, it's easy to forget why you're there. These are such nice people. They like me. They want to work with me.

Uh, sure. Whatever. So, shake their hands, eat their food, and date their assistants, but always remember: it's your job to get as much money as you can and still retain some semblance of creative control. After all, you did create the project. As distasteful as it might seem, recognize that you might not be the smartest person in the room and that only you have your best interest at heart. Once you've made that leap, you have to build a team of people who are on your side.

The best advice I ever received was to get a good lawyer. I liked mine so much, I got a second one with a different area of expertise. They play well together, look out for my interests, and define "legalese" in terms that my "low SAT-score brain" can understand. With their help, I'm able to do what I do best: create, write, shake hands and eat free food."

Randy and Jean-Marc Lofficier

Founded in 1985, The Starwatcher Agency was created by French artist Jean "Moebius" Giraud, Claudine Giraud, Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier. Its purposes are to assist comic-book creators in the selling and negotiating of the rights to their comic-book properties in the fields of motion pictures, television, animation and merchandising. It is also to help comic book artists find employment in the fields of concept design and storyboards.

"In 1987 we began working on developing Moebius' Airtight Garage as an animated feature. It turned into a real globe-hopping adventure. Our first attempt was to work with Les Productions Pascal Blais in Montreal. Pascal was a true Moebius fan, and loved the project as much as we did. Unfortunately we were not able to find the financing we needed and had to shelve The Garage.

In September of 1989 we were contacted by Renat Zinnurov who was working with the then Soviet animation studio Soyuzmultfilm. This was right in the middle of the Glasnost period, and the Soviets were looking to get involved in animation projects that would bring western currency into the country. The beauty of our arrangement was that the project would be entirely financed in rubles, and we wouldn't have to look for outside funding.

In November we traveled to Moscow for a week's worth of meetings on the project. It was an incredible experience, although a real eye-opener about how cultural differences can play a true role in story development and co-production.

Soyuzmultfilm is an extremely talented studio, but at the time their facilities were sadly out of date. Another, and bigger, problem had to do with the graphic language of our two cultures. Although they liked the art on the comic book page, they seemed unable to truly integrate what they saw into their own drawing. We were treated extremely kindly and well by all the people at the studio, but I believe also, that because of the political context of the times, there was a real problem in accepting American and French creative control of the project. Ultimately, there was just no way for us to get them to understand what we were trying to do, and the relationship dissolved.

We then met with an Irish studio which is now defunct. At the same time we were contacted by an investor from Florida who said he was able to put together independent financing for The Garage. This turned into the strangest of the experiences, as after many meetings the mysterious Florida investor turned to smoke. We never understood what he had hoped to gain by stringing us along. He certainly didn't get any money out of us. Unfortunately, what he did get were two of the very limited (20) leather bound storyboards that we had made as sales tools.

We had one final attempt to carry on the project with an independent producer who worked very hard for three or four years to pull The Garage together. At one time Akira Kurosawa was to be the executive producer, Katsuhiro Otomo was set to co-direct with Moebius and U2 and Brian Eno had agreed to provide the music. But we were never able to convince an American distributor of the value of the property. Perhaps the time was never right, or perhaps the project appeared too sophisticated. At any rate, we decided to take it off the market for the time being and wait until the climate is better for a film of this type.

Because this is a relatively complicated graphic novel, we had a fair number of choices to make when it came to writing the script. We wanted to keep the richness and flavor of the original, yet make the film accessible to general audiences. We therefore made some choices that could probably be the subject of hours of discussion. For some tastes, we probably kept too many characters from the original, but we all felt that they were essential to keep The Garage, The Garage.

Because of the complicated nature of the material, we also felt that having a script and graphic novel were not enough as sales tools. We discovered that most studio people only read the dialog in a script, which is totally inadequate when a fair portion of your story depends on the visual elements contained in it. We decided to commission a "sales" storyboard so that potential buyers would be able to more clearly understand the story we were trying to tell.

Although this was an expensive decision for a small company like ours, it proved to be wise investment. I believe we would never have gotten as far as we did with the project if we hadn't done it."