Feeling displaced, like a stranger in a strange land, lies at the heart of the directors' poignant and expertly crafted short film.

Michelle and Uri Kranot are not your average filmmaking duo. For one thing, they’re married. They also teach together, run a studio together, raise kids together, as well as make thought-provoking, sometimes in-your-face animated short films together. Most couples I know can’t agree on what color hand towels to use in the guest bathroom, let alone what compositing software to use on their next film. Then again, I’ve never spoken to Michelle and Uri about their tastes in textiles. But something tells me the discussion would be enjoyable.

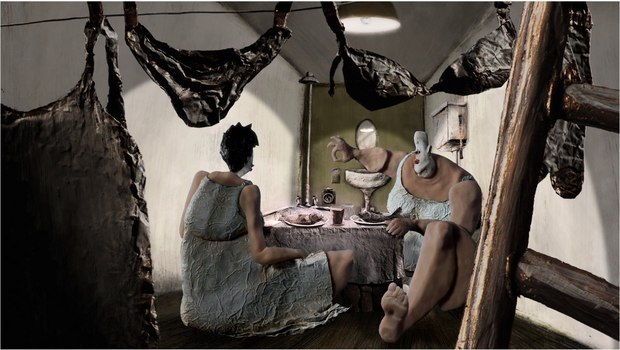

Their most recent film is Hollow Land, the story of a couple expecting their first child, whose journey across the sea to find a better life brings less than hoped for results. Shot under camera with flat clay puppets against digital backgrounds with a bit of hand-drawn 2D thrown in, the film blends a unique visual style with minimalist character animation and a haunting score, exploring issues of immigration, integration, assimilation and the pain, and hope, of charting a course in new, unfamiliar emotional and physical territory.

I had a chance to meet Michelle and Uri this summer in Annecy, as well as talk again to Michelle this fall at the Ottawa Festival. We talked about their history together, how and why they made this film as well as the many incidents and stories from their own lives that make Hollow Land both such a personal film as well as a film that resonates so powerfully with so many people.

Dan Sarto: When we met earlier this year in Annecy, we talked before I’d had a chance to see the film. I’ve seen it several times now. I’ve also seen a number of your earlier films, including The Heart of Amos Klein, and noticed a maturation of your filmmaking and storytelling style. Meeting you two, learning about how you met, married and moved from Israel to Holland to Denmark, has given me context to better understand your films. Hollow Land is a big film for you in many ways. Rich visuals, compelling story, exquisite music and sound design.

Michelle Kranot: I’m glad to hear you say that.

DS: The tone of this film is more subtle than any of your other films. Just as powerful, but not as in your face. More mature in a sense. There are many ways to communicate a message. It’s very different, however, when you hit someone over the head with an idea rather than drawing them in to discover it on their own.

MK: We’re older. You say more mature and it’s true. We don’t have the need to make anyone angry. In our previous films, you might see that as something a little bit juvenile. I’m not going to deny it. There’s something about wanting to stir things up, to make people upset about their own political opinions…

DS: I don’t look at that as juvenile, the desire to shake things up…

MK: This film also is much more personal. We had a lot more confidence as filmmakers.

DS: That confidence shows. You gave your story time to develop, to breathe. Filmmakers don’t do that unless they trust their material. Or, unless they don’t really care about their audience or making a watchable film.

MK: You also have to trust your producers. During the period we made this film, we actually wrote a number of different scripts. Our producers kept coming back to us, “Maybe you want to think about things like this, or in this way…” By the time the script for Hollow Land came about, we were very strong in our conviction, so we could present the piece and be open to input. Marc [Bertrand], our producer from the NFB, he had a lot of input into the script itself. Dora [Benousilio], our producer in France, also had a lot of input, mostly arguing with us. We really had to justify everything to her. She wouldn’t let us get away with anything. We had a lot of good support…

DS: …and a lot of good critical thinking to help tighten up the story.

MK: …Yes. We were in a position that we had enough confidence in ourselves to be open to that kind of input.

DS: Not everyone is. It’s tough to take criticism and accept critical assessment about such a personal story.

MK: Well, that’s part of growing up [laughs]. We didn’t compromise at any point. For example, our producers really didn’t like the idea of chapter titles. They kept telling us to forget about the chapter titles. They block the film, it stops the flow. They had a lot of criticism. But we could justify those titles.

DS: I liked the chapter titles. I thought they setup and framed the narrative very effectively.

MK: They set things up in the same way as chapters in a book, or even if you think about the way Brecht refers to theatre, that you have to be reflective. We don’t want the audience to be too immersed in the story. We want them to have moments when they step out of the story and think about it.

DS: It’s quite effective. Especially seeing the film has no dialogue.

MK: We had to justify all that. But once we got a green light, we could go ahead and do whatever we wanted. It ultimately was all good for the story.

DS: Let’s talk about the tone of the film. We talked about this in Annecy, the idea that you yourselves, moving from Israel to Holland, then to Denmark, have been strangers in a strange land. That’s what this film is about.

MK: We were strangers in a strange land in Israel and that’s where it really started. Everyone in Denmark thinks it’s a film about Denmark. Everyone in Canada thinks it’s a film about Canada. Everyone in Israel knows it’s a film about Israel.

DS: That’s my point. It’s more powerful, the abstract way you’ve presented the story, without any direct inference as to where the couple is from or where they’ve settled. Ending the film by showing all types of people floating adrift at sea draws attention to the fact that most people, at one time or another in their lives, in some context, have been alone, adrift, strangers in a strange land.

MK: The word I’d use is “displacement.” Everyone, even if they’ve never left their home town, at one point or another feels displaced. Our film is commenting not as much about immigration as about gender roles, the way we are culturally conditioned. You can feel displaced in any situation.

DS: Absolutely. That was the big message I came away with watching your film. By making this film about no one or group in particular, you made it about everyone and all groups all at once. What do you hope your audience comes away with after watching your film?

Uri Kranot: We have no doubt that people who’ve experienced displacement, immigration or any kind of move in their lives, will find it easy to connect to this film. However, we hope that those who never moved anywhere and live comfortably in their safe environment will have their moment of reflection and thoughts about those who were less "fortunate."

MK: It’s important that the audience feels, “Oh, this could be me. This could be someone I know.” A lot of people ask me, “So, is this a film about you?” I say, “Well, not exactly.” Then I explain to them that every generation in our family has immigrated going back centuries. My parents weren’t born in the same country their parents were born in. My children weren’t born in the same country I was born in. It goes way back. Every grandparent has their own horror story.

DS: So tell me how the film came about?

MK: When we first pitched the film, to get the funding, we said it was about immigration and “integration.” But it actually ended up being a story about a couple who try to fit in but don’t. All the pressures of society almost tear them apart but they emerge from their journey even stronger. It ended up being quite an optimistic film. I’m hoping people see the film and realize there is hope.

UK: It’s a heavy subject but I hope people feel the overall tone is optimistic. It’s not an autobiographical film but we are ourselves displaced people. We were born in Israel and moved to Denmark. Our kids’ mother tongue is Danish. They speak a language we don’t understand.

MK: It’s not just us but every single generation in our families has moved from one country to another. It’s a lot of people’s story. Altogether it’s not so much about immigration or moving. It’s about the whole concept of being displaced.

DS: What were some of the biggest challenges you faced making this film?

UK: Story-wise, it was difficult making a story that has many crossover points with our own life, without becoming too sentimental or hiding behind metaphors. Many symbols in the films are connected to specific events we experienced. But, we still we wanted to be less specific. Technique-wise, we chose to make these rigid puppets, with no facial expressions and not much range of movement. We weren’t trying to create emotional moments with them...that was a challenge, and we learned a lot about timing and the value of stillness, which is as important as movement. Method-wise, we had a pretty tight storyboard and animatic, but we were not sure about the ending. We wanted it to unfold as we made the film, letting us understand what the story was trying to tell us and not the other way round...which kept us very nervous during the production.

DS: Tell me how you made the film. Your previous films have been hand-drawn. This is stop-motion with flat puppets. Explain your choices?

UK: Our film started with a residency at the Fontevraud Monastery in France’s Loire Valley. No one talks there. Basically, you write. The film started from one image of people who have to put toilet plungers on their heads to be part of society. We started doing drawings. Little by little we got this story together about a couple who arrive at a place they think is a land of dreams but ends up being something far different. They need to adjust, conform or move on. The challenge on this film was deciding on a technique. Though we have a style, we try to take different approaches when we deal with a medium and technique. So this time, instead of drawings, we did old school under the camera flat puppets on glass, with bluescreen underneath. There are no physical sets. The sets are digitized.

MK: Everything is flat. You’re dealing with illusion of depth.

UK: We teach movement in animation. In this film, we wanted to do something where the movement was not taking focus. We’re so aware of overacting animation that hurts the eye. Especially in 3D. We went for a very rigid movement.

MK: It looks like cutout. It moves like cutout. That’s because the puppets are all very flat, except for their hands, which are 3 dimensional and have millions of replacement pieces. Some of their movement is very choppy, but other elements are very smooth. We’re combining a lot of techniques with stop-motion. Plus there is one surreal world sequence in the film that is hand-drawn 2D. I wanted the thrill of working under the camera where at the end of the day you could push “Play” and see something happen. Amos Klein was also a long project, hand-drawn animation, going back and forth, back and forth. With Hollow Land, we wanted something where the process was a little more rewarding.

DS: You’ve got three different producers from three different countries. Did they come in at different times? How did you stitch this co-production together?

UK: It’s a poker game. The NFB wouldn’t go in until we had the French producers on board. You’re trying to get commitments, trying to convince people you already have funding in place. But we put it together and we’re so pleased with the working relationships and the results.

MK: It’s funny. We’re not French. We’re not Danish and we’re not Canadian. But the film is funded from France, Denmark and Canada. This is the second time we’ve worked with Dora [Les Films de l'Arlequin] and Arte, the French Film Fund. We have a track record. It was hard putting this together, but it was easier than when we did Amos Klein. Back then no one knew us. We were lucky.

DS: I don’t normally pick up on the music but on this film I did. Your music was subtle, but very rich and deftly woven into the film. So often with young filmmakers, sound and music is an afterthought, slapped on at the end.

MK: It’s carpeting.

DS: Exactly.

MK: Uri wrote the music and played the music as well. We had the music at the animatic stage. We had it early on. The film was basically there at the animatic. We settled on a technique afterwards. Uri worked on the music with Normand Roget from the NFB. At first, he gave Normand this piece of music and said, “These are some of my ideas. But I’m looking forward to hearing what you want to do with this film.” Normand said, “You’re the composer. I’ll just arrange it and make sure it sounds great.” Uri said, “No, you’re the master and I’m not even a professional musician!” Uri was very honored and humbled to work with Normand. Normand complimented Uri’s piece, enriched it and made it happen. Recording the music in Montreal, it’s been a very gratifying process to work with such professionals.

My little bit of input into the sound design was the plumbing…the pipes. I wanted to hear the building all the time. And I didn’t want the music to take over the film. If you notice, there is only music in-between segments when the chapters come up. There isn’t music playing throughout the whole film.

DS: How did you get together as filmmakers?

UK: We went to the same art school in Israel but didn’t really meet until we both went to the festival in Annecy.

MK: Yah, we actually met in Annecy. We had our student film there and have been together since. A very romantic start.

UK: We decided we couldn’t do what we wanted to in Israel, from a political standpoint. So first we moved to the Netherlands, then we got involved with The Animation Workshop in Viborg and moved to Denmark. We teach there, we have a studio as well to make our films. We started after they invited us to be artists in residence. We are very lucky to be in the situation we are in in Denmark. We were also teaching for a time at the Bezelel Art Academy in Jerusalem. Unfortunately, in Israel, we’ve been tagged as political filmmakers. We’re running away from that actually.

MK: It was so wonderful that after the screening of our film in Ottawa, people asked me questions about my technique. Nobody was accusing me of being political.

DS: No one was attacking your politics?

MK: This was very refreshing. Someone actually wanted to have a discussion about the way different people in different cultures see the same story.

DS: Do you think people attack your politics because it’s easy? You’re an easy mark to try and get riled up? Or are they really interested in talking politics?

MK: It’s a point of entry for a lot of people. Especially if they’re into writing news or articles. Nobody in the general public really watches these films, so journalists need a hook to get people reading a story about an animated piece.

DS: I can appreciate that

MK: I can appreciate that too. It’s a point of entry. So they want to push that point. It’s usually not the most interesting point for me, but I can go along with it. Except that in a context where there are a lot of people, the general public asking questions, sometimes it’s a superficial activity. They already have an opinion and it’s about them, not me or my films. They need to express their opinion. I’m not being critical. I’ll go along with it. But…

DS: It’s nice to talk about something else for a change.

MK: Yes. But I don’t think we’re political filmmakers. We just make films.

Hollow Land (Terre d'écueil) (2013)

14 minutes

Directed by Michelle and Uri Kranot. Produced by Marie Bro for Dansk Tegnefilm in co-production with Marc Bertrand, the National Film Board of Canada, and Dora Benousilio, Les Films de l'Arlequin of France. Supported by the West Danish Film Fund, the National Film Board of Canada, CNC, Arte and The Animation Workshop in Viborg.

Michelle and Uri are teachers and artist in residence at The Animation Workshop, Denmark's leading animation institution, with activities focused on education, culture and business development.

--

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.