Every Tuesday, Chris Robinson digests and dissects (relatively) new indie animation short films. Today's short is Judith Poirier's Two Weeks - Two Minutes (2013).

Contrary to what some animators might think and feel, they’re all unsung. In our little universe we might all know the names Plympton, Miyazaki, Lasseter, Hertzfeldt, Kovalyov, Schwizgebel etc… but let’s face it, the general audience, hell even many creatively engaged folks have no fucking idea who most of these people are. Animation tends, unfortunately, to be defined by studios and an array of cardboard or idiotic characters.

Where was I?

Oh right…so… even within our little quirky animation universe there are some amazing voices that we don’t really acknowledge enough - for whatever reason (sometimes because the artists don’t like to be pigeonholed as just an animator or filmmaker or whatever). One of those quieter voices emanates from Canadian artist, Judith Poirier.

A graduate of the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London, Poirier lives in Montreal and teaches at teaches at the École de design, Université du Québec à Montréal. As a filmmaker, her animation work explores the relationship between cinema and books through the use of typography, book design and printmaking.

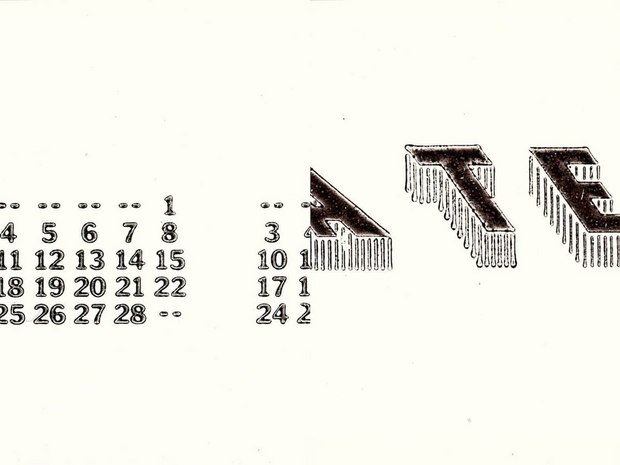

Two Weeks – Two Minutes (2013), which won the Canadian Film Institute award for Best Canadian animation at the Ottawa International Animation Festival, was created during a two-week residency in Chicago. Both the image and sound were printed directly on 35mm using letterpress (and immediately makes me think - see above - of Lizzy Hobb’s recent ‘typewriter’ film G- AAAH along with Ed Ackerman’s 1988 classic Primiti Too Taa)

Two weeks of memories, impressions and experiences are compressed into a two-minute split-screen work that feels like you’re speed reading a James Joyce novel while on a boat at sea during a mild storm.

In creating these dizzying smudges of marvel, Poirier challenges our accustomed ways of reading and processing information (should we ‘read’ the film left to right? Right to left? Top to bottom?). At the same time, as the images race by it starts to feel as though we’re watching an out of whack, discombobulated flipbook (itself another example of the long lovefest between print and animation).