Joe Strike gets the lowdown on the new series from Bob & Margarets Snowden & Fine.

There's a new cartoon star in town, and his name is Ricky -- Ricky Sprocket, Showbiz Boy, to be exact.

Actually, it remains to be seen whether Ricky will achieve the same stardom outside the cartoon realm as he does within his own series. In it, Ricky is the most famous child star on the planet with all the wish-fulfillment possibilities -- and complications -- that suggests, along with the more down-to-earth problems that any kid has to deal with.

Ricky is the creation of husband-and-wife animators Alison Snowden and David Fine. The pair is best known for their Oscar-winning short Bob's Birthday and the series it inspired, Bob and Margaret, broadcast around the world and in the U.S. on Comedy Central.

It's their first children's show, based on "an idea we had a number of years ago," says David Fine. "We had some Hollywood experiences that kind of inspired us," he adds without going into detail.

"We wanted to do something inspirational," Alison Snowden offers. "When they show child actors in movies, they seemed always to be bitching. We wanted to do something more positive and inspire kids a bit -- but incorporate actual problems they go through. It's something to dream about -- Ricky can do anything he wants."

Ricky's Hollywood is of the old-fashioned variety, more Singin' in the Rain than The Player, although Fine points to the Coen Brothers' Barton Fink as one source of inspiration, "but without the burning hallways." Ricky is employed by Wishworks Studio, where he deals with the studio's blowhard boss Mr. Fischburger, perfectionist director Wolf Wolinski and not-so-nice rival child star Kitten Kaboodle. Even though Snowden and Fine pictured Ricky as an alternative to that overly-precocious stereotype, Snowden admits that "we needed someone [like that] in the show" for their real star to play off.

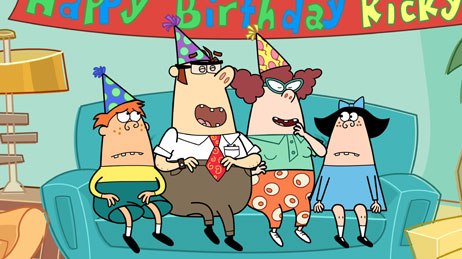

The non-showbiz half of Ricky's life focuses on his family and friends. Waiting for him back home are no-nonsense mom Bunny, goofy, sausage-making dad Leonard, and Ethel, Ricky's sister-from-hell. "Ricky is almost an everykid," says Snowden. "We wanted the show to have some edge. It's a sibling rivalry, but they're not always shouting -- it's a silent but deadly rivalry. She's the complete opposite of Ricky: she's basically charmless, barely moves and says the absolute minimum."

"One element about her comes out in subtle ways, Fine adds. It was bigger in [the show's] bible, but now it's part of the show's subtext: even though no one else does, her parents see Ethel through rose-colored glasses as a delightful, sweet little girl -- sometimes even as the one with real talent, not Ricky."

There's yet another female character on showbiz boy's case: entertainment reporter Vanessa Stimlock, who makes Ricky her number-one story. With three women giving Ricky a hard time (counterbalanced by his mom and pal Alice), the show seems particularly boy-centric; put it together with Phineas and Ferb's frustrated sister Candace and one wonders if it's a bad time to be a cartoon gal. "I saw that [Phineas and Ferb] too," says Fine, shrugging off the annoying-girl motif. "I guess it's a popular thing."

Ricky's episodes interweave his big-screen adventures with his day-to-day, being-a-kid experiences, which usually means bookending episodes with scenes from his latest movie. "We've done episodes where Ricky is in the studio or on location shooting a film as the starting point" says Fine, "then something goes wrong and we build the story around that." Snowden adds that Ricky often uses his film skills and movie props to save the day in real life. As one might imagine, the premise gives Snowden and Fine ample opportunity to spoof any movie genre imaginable, from cowboy, spy, crime and superhero flicks onward.

As Fine explains, "we try to reference other films, but not in an obscure way. We're careful to make sure you don't need to know [the film being spoofed] and make it work on different levels." Sometimes the targets are as obvious as 2001's computer HAL, and sometimes as subtle as Peter Sellers'Being There. (When Ricky's sausage-obsessed dad compares the film business to cranking out sausages, his observation is mistaken for profound wisdom; a high-level studio job and hilarity quickly ensue.)

Snowden and Fine resisted the temptation to make an entire episode a Ricky movie from beginning to end. They've come close once or twice though, as in an episode when Ricky's mom accidentally launches the family into space in lieu of the actors who were supposed to accompany their son. Other episodes are built around the side effects of showbiz fame: product endorsements, studio publicity, complications with his real-life friends, and even the very grown-up worry of being supplanted by a more popular star.

Speaking of sausages, Snowden defines the design of Showbiz Boy's characters as "kind of like sausages," with neckless heads that attach directly to their bodies. They're obviously kin to the people populating Bob and Margaret, who Fine describes as "cuddly and round, with big round noses. They were wiggly in the original short in Ricky Sprocket Alison set out to do a bolder style," one that would lend itself to being animated in Flash.

Snowden and Fine did not need to be talked into employing Flash technology; they had already been exploring it on their own while developing their new show. "We love designing our shows and writing the story," says Snowden, "but the [production] process was dragging us down. [Flash] and the way it speeds up our production is the answer to our prayers."

Snowden and Fine switched over to digital ink and paint for Bob and Margaret. "It was a step forward at that time that we embraced," Fine explains. "Now we're moving another step with Flash. One reason we chose to work with Studio B was that we thought they'd do a great job using the technology."

The pair's relationship with Studio B began with service work the studio did on Bob and Margaret and deepened with Simon Stimple, a series they jointly developed for Canada's Teletoon channel. "I really liked that show, but it never got off the ground," reminisces Studio B's Blair Peters, one of Ricky's executive producers. "It was probably more like a Detour kind of show," he adds, referring to Teletoons version of Cartoon Network's Adult Swim. "Then they came to us with Ricky Sprocket and we just loved the concept."

The Sprocket pilot itself was actually produced at another Vancouver studio, Atomic Cartoons; when scheduling problems intervened (and an unexpected slot opened up in Studio B's production schedule), the series made its move. While not the deciding factor, Studio B's "fantastic view of [Vancouver's North Shore] mountains" (according to Fine) may have also contributed to his and Snowden's decision.

Fine described Studio B as "very much a creative partner" throughout the production. "We're thrilled with the look" of the show, he adds, praising the Vancouver studio's entire animation team and singling out series director Josh Mepham in particular. About 40% of the series is actually animated at Studio B, with the remainder farmed out to Top Drawer in the Philippines. "We do a lot of reshoots and tweaking in Vancouver. With Flash you can open the files wherever you are and adjust the animation -- it offers you direct control. In [digital] 2D you can manipulate composition or move your field, but you can't redo your animation."

Ricky premiered this past September on Canada's Teletoon, and in January on Nicktoons with 52 11-minute segments packaged into 26 half-hours. "We're pleased to have a worldwide deal with Nickelodeon," Fine enthuses. "We'll be on every Nick outlet in some 127 countries."

And as for a second season -- will Wishworks (or Nickelodeon) pick up Ricky's option? "It's in the hands of the gods, or in this case the broadcasters," says Fine. "Nickelodeon wants to see how it performs in the U.S. before deciding on a second season.

"Now that the first season's done, we're looking at different ideas. We're not sure if we'll be doing more Ricky or something else. We're just assessing the lay of the land, trying to figure out what we want to do next -- we don't have a project we're jumping to.

"You spend a lot of time developing, pitching and making a show. You need to take a breath.

Joe Strike is a regular contributor to AWN. His animation articles also appear in the NY Daily News and the New York Press.