In the first of a two-part series from the Inspired 3D Short Film Production book, Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia delve into why storyboarding is so important.

A picture is worth a thousand words.

Now that youve come up with a great plot, one or two strong characters, and an idea for your overall art direction, its time to start figuring out how your storyline is going to flow visually. Your first opportunity to do this is by drawing storyboards. A set of storyboard panels is like a preliminary comic-book version of a film (see Figure 1).

Storyboards are the bridges between a written script and the visual world of cinema. If you wrote out your story in script form, hopefully you imagined how each scene and action would look onscreen. If not, read through your story again and try to picture the best possible way to stage each story beat.

Staging refers to the ways in which individual story beats or actions are clearly presented in visual terms. Effective staging comes from a successful combination of camera angles, point of view, composition and placement of characters and objects.

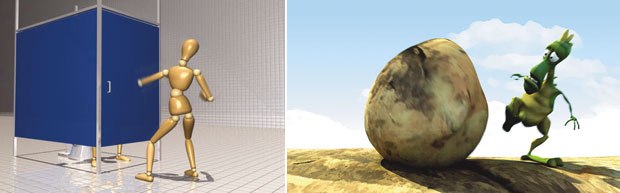

The first step in realizing your ideas for how your story will translate into cinematic imagery is by getting them down on paper as storyboard panels. Storyboards can be quick and extremely rough little sketches, often referred to as thumbnails, or they can be carefully crafted works of art in their own right (see Figure 2). The level of refinement of your storyboards will depend on the structure of your team, your drawing skills and your deadline. If you are working alone, you can make them as rough as you want as long as you understand your own visual shorthand. If you are working with a team, they should be a bit more refined.

Although it is tempting to overproduce your storyboard panels into fine works of art that will look impressive when featured in the documentary on the making of your film, dont inadvertently slow down your production by focusing too much attention on what are often considered little more than throwaway templates and staging suggestions. Your storyboard images should be refined enough for you and your teammates to be able to read and interpret them clearly, but rough enough so that your schedule does not suffer unnecessarily.

Also, the style of your drawings should match the overall art direction that you are envisioning for your film. If you are creating a goofball comedy with exaggerated characters, try to draw your boards in a similar fashion. If the visual elements of your film are to be abstract or symbolic, it is neither appropriate nor necessary to draw realistic characters on your boards.

Why Storyboard?

Since you are in the process of creating a film rather than a piece of literature, it is not enough to simply work out the beats of your story on the written page. Cinema is a primarily visual medium; therefore, working out your narrative flow with pictures rather than mere words is often a necessary step in discovering if and how your written or imagined storyline will translate into film. Storyboarding allows you to begin figuring out the best way to express each story beat visually.

In addition to exploring the visual flow of your narrative, storyboarding also provides you with a first opportunity to begin working out the cinematic specifics of your film, including camera angles, composition, point of view, hookups and continuity, object and character motion, cuts, sight gags, posing, facial expressions and, to some degree, pacing.

However, keep in mind that these cinematic issues will mainly be ironed out in the layout, 3D-animatic and animation stages. You definitely want to start thinking about these details when drawing your storyboards, but realize that you are still in pre-production mode. The main purpose of this development step is to continue refining the actual flow and continuity of your storyline with visuals.

Although it is not necessarily required that you storyboard your film, it is certainly highly recommended. Some stories are indeed simply better left in literary form, but most can successfully make the transition into cinematic form if done with an eye toward composition, staging, action and clarity. Even if you simply create rough thumbnails on notebook paper, the earlier you start working out these cinematic issues and the overall plot progression of your film, the better. Remember that the cost of revisions increases steadily as production continues. It is much easier to fix a structure or pacing problem at the storyboard stage than when you are in the midst of animating and rendering your shots.

Some short film authors actually begin their filmmaking process by storyboarding before (or even instead of) writing out their plot in text form. You might find this to be a preferable method of initially getting your story idea down on paper, especially if you are planning a film with no dialogue. Afterwards, you may or may not find it necessary to express your story in written form as well. The pictures alone might suffice.

Suppose you have actually recorded your story as printed text. Once you begin enhancing your words with pictures, you might discover flaws or pleasant surprises in your plot structure. Some written passages simply will not translate successfully into cinematic form. For instance, you might find that it is inappropriate or even impossible to visually represent all of those cultural and historical setting details that you so eloquently described on the printed page. Perhaps this discovery will indicate that you require some additional dialogue or narration. You might find that your chase scene actually needs a lot more screen time than you originally imagined. You might decide that scene 10 should actually take place before scene 9. Your boards might reveal that you had envisioned too many low-angle shots and that they will eventually lose their dramatic impact. Or you might discover that the (hopefully) amusing sight gag you tentatively described in your script will actually work after all, now that youve seen it in picture form.

Keep in mind that the storyboard stage is an exploratory process in which a fair amount of story editing will undoubtedly take place. Your script might have seemed perfectly tight and well paced in its written form, but as you draw your storyboards you will very likely make a few changes perhaps even some major plot restructuring. Also, remember that storyboards should be considered preliminary suggestions of shot staging, not necessarily absolute directives. Dont feel that you need to work out every minute detail of your cinematic vision during the storyboard process. You will undoubtedly discover better ways of staging certain shots once you start seeing and refining them in the animatic, animation and rendering phases of your production cycle (see Figure 3). Maintain an attitude of flexibility and allow yourself to tweak your story on occasion if the current stage of your production compels you to do so. Just make sure that each change is motivated and results in an improvement of your film as a whole.

Another good reason for storyboarding your film is that it will be much easier to pitch your cinematic vision to your boss, your financial backers, your teachers, your mom or your teammates if you can present your story with images. Many such audience members will not share your ability to visualize your narrative actions in their minds eyes if you pitch your story with words alone. We all know what a picture is worth, after all.

Principles of Preliminary Shot Construction and Scene Planning

A story beat is a narrative term that describes a particular event or action, such as a conversation, a chase, a fight or a quiet moment of reflection. Every beat of your written, recorded or imagined storyline will be represented cinematically by a scene, which will consist of one or a series of shots.

A scene is a complete story action that typically takes place in a singular location. An exception would be a chase scene that spans several different locales before reaching its conclusion.

Go through your written or imagined script, separating it into individual scenes and assigning each one a two-word name that effectively describes the story action, the setting or perhaps both. For example, wife cooks, chase Butch or cat barbecue. Abbreviations of these scene names will be used when you label your boards and schedule your production, so watch out for duplicates. Chase Butch and cat barbecue will both become CB, so it would make sense to perhaps change the latter to backyard barbecue or BB.

A shot is a cinematic term defined as the space between camera cuts, and will typically be identified by a number appended to a scene abbreviation, such as WC01 or CB12. A shot is the presentation of a complete or partial story action from a single, but not necessarily static, point of view. This point of view can drift or zoom as necessary to follow or help tell the story of a given shot. Once the shot cuts, fades or wipes to a different point of view, a new shot has been initiated. If you stage a quick dialogue exchange between Janice and Larry by showing a close-up of Janice, then cutting to a close-up of Larry and finally cutting back to Janice, youve created three distinct shots. If you stage this scene from a single, static POV that frames both characters, or you have the camera pan back and forth between these two individuals, the conversation will be contained within a single longer shot (see Figure 4).

A one-to-one relationship does not necessarily exist between shots and story beats. For instance, a single story beat might require several shots to be presented effectively and dramatically. In the aforementioned scenario, the story beat is the short conversation between Janice and Larry, which might be delivered with one, three or perhaps a greater number of individual shots. Conversely, a single shot might contain more than one story beat. A lengthy action sequence that contains several distinct and important plot points might conceivably be delivered within the span of a single and particularly lengthy tracking shot. Famous long tracking shots exist in films such as The Player and Goodfellas. Some short films, such as Framed, Toilet, Squaring Off, Luxo Jr. or Top Gum, are in fact entirely contained within the space of a single shot, where the point of view may drift and pan, but the camera never cuts even though several story beats are delivered (see Figure 5).

No matter how many shots are required to describe a single story beat, every shot needs to be represented by at least one storyboard panel. Use the least number of panels per shot to effectively describe the action, staging, composition, and point of view. If the purpose of a particular shot is to simply establish a locale, one image should suffice one shot, one storyboard panel. If an action or a camera move occurs, you might need one storyboard to indicate the beginning composition and story situation of the shot and a second one to indicate the end, or perhaps just one elongated rectangle one shot, one or two panels. A lengthy chase scene that youd like to follow with a single extended tracking camera move might require several associated storyboards one shot, several panels. In general, a single image, a few descriptive notes or arrows and a secondary frame (if appropriate) will sufficiently describe the action of most shots. The number of shots and corresponding images required to describe the action of an entire story beat will vary considerably.

![[Figure 6] Every necessary shot in a film contains an actual story beat, even if there is little or no actual action taking place. [Figure 6] Every necessary shot in a film contains an actual story beat, even if there is little or no actual action taking place.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2376-shorts05-06.jpg?itok=naou6E_T)

Every shot in a film is indeed like a miniature story on its own. Most shots will have a beginning that directly relates to the previous shot (unless it is the first shot of a new scene). Each shot will also have a main action, which is the most important piece of information to describe in a storyboard panel. And every shot will have an ending, which will lead into the next shot in the sequence (assuming one exists). This mini story might require any number of storyboard panels to be described effectively. Even the absence of action can be considered a mini story. A story in which Fred sat very still in his chair and did not breathe or blink contains no movement whatsoever, but Freds stillness is undoubtedly related to something that has happened or is about to happen in an adjacent scene (see Figure 6). Perhaps he is reacting with shock to something he just heard on the radio. Maybe he is meditating in preparation for battle. Or perhaps he is sleeping or has passed away.

You must identify and storyboard the main action of each shot. You should only board the previous, subsequent, or secondary actions of that particular shot if they are necessary to tell the mini story that is currently taking place. You often can describe these extra actions just as effectively using text instead.

Establishing shots often dont contain any action, but the message that you are here is still a story being delivered, and it must be told effectively with appropriate images, icons and descriptive text.

There are many kinds of shots wide shots, medium shots, close-ups, extreme close-ups, birds-eye views, worms-eye views and over-the-shoulder shots, just to name a few (see Figure 7). Use the appropriate angle and point of view to most effectively tell the story of any given shot. If your film is about a very small child, a fair amount of low-angle up shots will probably be appropriate. Wide shots are generally used to establish a new locale, while close-ups are often effective for conversations, reaction shots or inserts (in which the screen is filled with a pertinent object, such as a ringing phone, a bruised and throbbing finger or the numerical display on a ticking time bomb).

Mix it up. A film made up of only wide shots will not be very dynamic. But dont mix up angles and points of view arbitrarily or repeatedly. Every point-of-view change needs to be motivated by the need to stage a new or existing action more effectively. Cut to a different camera angle only when it feels as if the audience will want to see the current or subsequent action from a more interesting or revealing point of view. An example would be a wide establishing shot that cuts to a close-up of a character in the midst of an action or a conversation (see Figure 8).

Also, it is often a good idea to hook up individual shots by motivating a camera cut with an action, such as a character looking or pointing in a particular direction, where the object of interest is subsequently revealed after the cut (see Figure 9).

Pay attention to a scenes line of action, which is indicated by the direction in which an object or character is facing, traveling or conversing. Be wary of crossing this invisible line when changing perspective from one shot to the next because it can be particularly confusing to your viewers (see Figure 10). Sometimes simply mirroring the offending image from left to right can solve a line-of-action crossing error. Give this a try if you discover such a problem in one of your image sequences.

If a change in point of view is timed to the exact moment when the viewer feels the need to see a new or existing action from a different angle or POV, then the cut will seem smooth and appropriate.

Watch a few of your favorite films, pausing on each new shot to identify its type. Does the director use a lot of extreme close-ups? When he establishes a scene, does he start with a wide shot and then gradually zoom into the action, or does he prefer an actual camera cut? How does his typical shot selection contribute to the overall style and feel of the film?

Apply traditional principles of image composition when staging and boarding your shots. If someone freeze-frames your film at any given point, the resulting image should hold up as a well-composed, static work of art. Balance, depth, overall shape, symmetry, natural randomness and lines of action are a few of the main composition principles to study. Consider the action of each shot and compose accordingly. For instance, if a struggle is taking place, an off-angle composition will help deliver the feelings of imbalance and uncertainty (see Figure 11).

Decide on the central focus of each shot and choose an appropriate camera angle and composition so that the audience does not have to search for the visual story-point messenger. Or, break this rule if you deliberately want your audience to be unsure about where to look, like when staging a shot through the eyes of a pursued victim in a horror film.

Also try to avoid basic design errors, such as edge and object tangents, that create depth ambivalence. Read a few books on drawing, painting, photography, film directing and shot construction and apply what you learn to the composition of your storyboard images. Review existing films and storyboard drawings to see how the pros compose and stage their shots. If youre not sure whether a particular shot is composed nicely, try blackening the objects and characters of the associated storyboard panel. Creating such silhouette images is often a very effective method of objectively analyzing the overall composition of a shot and quickly revealing balance or tangent problems (see Figure 12).

Carefully consider the intended use of camera moves or more to the point, the overuse of camera moves. Only move the camera within a single shot when the action or mood calls for a corresponding and appropriate staging shift. Following a moving object, tracking over to see where your hero is pointing, panning over to the other conversation participant, pulling out from a close-up to reveal a locale and zooming in to increase the intensity of a characters facial expression are all good reasons for camera moves. However, the simple fact that it is easy and often tempting to create large, flying camera moves with your CG software is not sufficient reason to do so with reckless abandon. Sometimes large, sweeping camera moves are indeed quite appropriate, such as when you are following a jet fighter chasing a UFO, intentionally creating the feeling of vertigo, or dramatically staging a shot through the eyes of an attacking werewolf. Most of the time, however, camera moves are rather subtle and limited. Watch live-action movies carefully you might be surprised at how rarely cameras actually move. Granted, that is partially due to the fact that real cameras are a lot more cumbersome to move than their digital counterparts, but remember just because you can do something, doesnt always mean you should.

When planning camera moves, envision that a real cameraman is filming your action. He will sometimes follow a half-step behind the movement of a character or an object rather than run exactly parallel, especially if the action is swift. If you want to indicate such a camera movement offset, draw your storyboards appropriately with the main action slightly off center (see Figure 13). Another example is the idea of the psychic cameraman, who anticipates a destination by revealing the locale before a character gets there (see Figure 14).

Take advantage of the fact that you are creating a 3D film and use depth appropriately and creatively as you stage your shots and scenes. Flat compositions tend to be a bit boring. Use subtle or occasionally extreme angles to increase the feeling of dimensionality. But be careful of overusing extreme camera angles; doing so will make them lose their dramatic impact. Motions should not be restricted to left and right or up and down. Think of each image as a box where your objects and cameras can move in and out.

Also remember that you are creating an animated film in which exaggeration is often necessary, especially when it comes to visuals. Work the necessary amount of exaggeration into the characters and objects of your storyboard panels to convey the desired style and clarity.

Always think in terms of continuity. Each shot is part of a greater whole. Focus on the shot at hand, but think about how it relates to the rest of the scene, and in turn how that scene relates to the overall flow of your entire story. Remember that every action is a step along the pathway toward your storys ultimate conclusion.

To get a copy of the book, check out Inspired 3D Short Film Production by Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia; series edited by Kyle Clark and Michael Ford: Premier Press, 2004. 470 pages with illustrations. ISBN 1-59200-117-3 ($59.99). Read more about the Inspired series and check back to VFXWorld frequently to read new excerpts.

Jeremy Cantor, animation supervisor at Sony Pictures Imageworks, has been working far too many hours a week as a character/creature animator and supervisor in the feature film industry for the past decade or so at both Imageworks and Tippett Studio in Berkeley, California. His film credits include Harry Potter, Evolution, Hollow Man, My Favorite Martian and Starship Troopers. For more information, go to www.zayatz.com.

Pepe Valencia has been at Sony Pictures Imageworks since 1996. In addition to working as an animation supervisor on the feature film Peter Pan, his credits include Early Bloomer, Charlies Angels: Full Throttle, Stuart Little 2, Harry Potter and the Sorcerers Stone, Stuart Little, Hollow Man, Godzilla and Starship Troopers. For more information, go to his Webpage at www.pepe3d.com.

![[Figure 12] Silhouette drawings are helpful for examining overall composition issues, such as balance and negative space. [Figure 12] Silhouette drawings are helpful for examining overall composition issues, such as balance and negative space.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2376-shorts05-12.jpg?itok=3NK1Lug8)