Tara DiLullo takes a ride with the visual effects wizards who raised the bar for CG-enhanced talking animals in Racing Stripes.

Technology in filmmaking has made astounding improvements since the television days of Mr. Ed, when audiences bought the illusion of a talking horse through the “magic” of chewing and lip-synching alone. With the quantum leaps in visual effects software enhancements over the past decade and a half, the live-action talking animal genre has seen an evolution in quality and believability with each new project. Just since 1995 and the release of Babe, which became a popular benchmark for the genre, the techniques and methods for believable conversation between animals have improved significantly. With the film Racing Stripes hitting theaters Jan. 14, the genre has again raised the bar in bringing to life some of the most impressive and impossible animal kingdom conversations ever to grace the big screen.

Former animator and Quest for Camelot director Frederik Du Chau makes his live-action debut with Racing Stripes. This family friendly film tells the tale of Stripes (voiced by Frankie Muniz), a zebra whose ambition in life is to be a racehorse. With the help of a menagerie of vocal barnyard friends, Stripes learns to never give up, despite the prejudices of both small-minded humans and equines that want to squash his dreams. In bringing Stripes and his pals to anthropomorphic life, Du Chau turned to Digiscope’s visual effects supervisor Dion Hatch to create and coordinate the various effects needed to make these chatty critters believable. Hatch explains that the collaboration worked well because of their mutual respect for each other’s expertise and creative input. “Some directors have no idea about the visual effects, from the technical side, or aesthetically what can be accomplished,” Hatch explains. “Frederik is very up on the visual effects world and he spends a lot of time reading all about it. He also has a 2D animation background, so he is very experienced in that world. The way this film was conceptualized and finalized, it worked due to the fact that Frederik storyboarded out every shot and in the way he shot the film. When an animal talks in Racing Stripes, you see it turn its head, while it is simultaneously talking. [In] a lot of the earlier movies, because of the technology, they had to keep the animals more static. So we tried to get a lot of head movement and I think it helped push the look further.”

Of course, the Racing Stripes concept quickly brings to mind the infamous W.C. Field’s adage, “Never work with children or animals,” and that still stands true for any filmmaker dealing with those potentially unruly subjects. Countering the natural tendencies of animals to not interact peacefully or on command was a constant battle for the filmmakers on the set and, in turn, for the post process. Hatch says working around those issues became core to the success of the film.

“Obviously, animals aren’t going to do what you want always. So what Frederik did was storyboard every animal and set up every dialogue line. For example, in the case of Tucker (voiced by Dustin Hoffman), he is a curmudgeon donkey coach who trains Stripes, and he has a lot of scenes with Frannie the goat (voiced by Whoopi Goldberg), where they banter back and forth. On the set, you had to have one turn to the other, while `talking’ and to get two animals to do that, well, major kudos to the animal trainers! Each animal had one trainer and they would run back and forth to get the animal to look one way or another. A lot of times it didn’t work, so we would have to do a split screen to get it to work out. Plus, a lot of these shots also had bluescreens because you can’t put certain animals together with other animals. There were a lot of times we would have to roto off the animals and put them in other scenes. A zebra isn’t the nicest animal, which we didn’t want to portray in the film,” he chuckles.

“There would be nights, like during the Blue Moon Race sequence, where Stripes challenges his nemesis, Trenton’s Pride (voiced by Joshua Jackson). When we first started shooting in South Africa, we spent a lot of cold nights trying to get them all to behave. A number of times, Stripes tried to take a chunk out of the Clydesdales and vice versa. But overall, Stripes motion worked out well.”

The bulk of the visual effects for Racing Stripes revolve around the plethora of conversations that happen between animals. Hatch details, There were roughly 760 visual effects shots. At [Santa Monica-based] Digiscope, we did about 340 shots and about 277 were done at Hybride Visual Effects in Quebec, Canada. We had creative alliances with a number of other companies, but we were sort of the hub. Hybride did the comedy relief flies, Buzz (voiced by Steve Harvey) and Scuzz (voiced by David Spade), Frannie and the majority of the Tucker shots. We did the whole Blue Moon Race and the mouth movements.

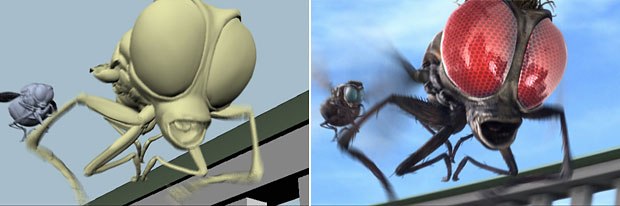

In terms of software utilized for the project, Hatch adds, When you are looking at the animals, you are looking at the eyes. For Goose, the pelican, we did a lot of eye expressions in 2D on the inferno. Hybride used SOFTIMAGE|XSI and a lot of their eye expressions were done on 3Dside, so it was a combination. For the unique computer-generated characters of Buzz and Scuzz, Hatch suggests they evolved in form and content throughout the filmmaking process. We asked a number of different companies to compete for Buzz and Scuzz. Right from the top, Hybride did a lot of funny things with them and their animation was superior. Originally, Frederik said he wanted the flies to be extremely realistic. As things went on, he changed his concept of them, finding out it was funnier if Buzz had a buzz haircut and you could see them talking. The writers did more dialogue for them and they metamorphosed into these fun characters.

Digiscopes goal of creating more seamless and believable mouth movements during the animal conversations came to fruition through the calculated efforts of intense planning, better software technology and good old-fashioned trial and error. Hatch explains, We discovered a lot in the back end. One thing, in particular, is that if an animal is actually moving their mouth thats bad. In the old days, they used the peanut butter trick [feeding animals for mouth movements] and found areas that they could use to fit the dialogue, but, of course, the lip synch was completely off.

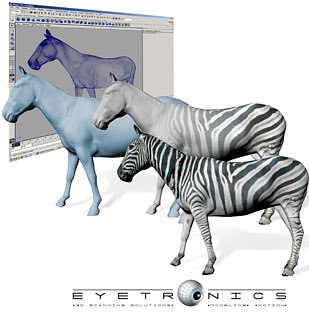

Later, as the technique began to develop, they would still do that, but find places they could morph between mouth motions. Babe was a 3D texture bake. What we are now doing for Racing Stripes is photometric projection. We are re-projecting the original photography back onto a 3D model of the muzzle, or sometimes the full head. Wed take the 3D scans and conform those to the animals, called a soft track. Once we have re-projected those textures back on, we then do the talking. But if the animal is munching away, we had a very difficult time trying to conform the geometry to that motion. In most cases, we had to get rid of it. But if the animals best take had them chewing, we would go back and eliminate the mouth motion. Those shots were the most time intensive because we had to texture bake from all sides and we couldnt use original photography for every frame. Things have changed a lot and there are [many] programs that can do it automatically now, but we ended up doing it the old fashioned way by setting up morph point positions for the head and then animating. Randy Doorman was our animator and he did all of the talking animals here at Digiscope and he got used to doing the old squash-and-stretch.

Eyetronics, with its lightweight camera-based system and ability to scan on location, was chosen to handle the 3D scanning of the animals. Since the film was shooting in South Africa, Eyetronics dispatched two of its scanning technicians, Desi Varintel and Tom Van Laere, from its headquarters in Belgium. Nick Tesi, vp of Operations for Eyetronics in the U.S., notes, We actually did an initial scanning test here in California on [Digiscope president] Mary Stuarts horse as a proof of our technology. Based on the success of that scan, Eyetronics was awarded the Racing Stripes project.

Tom Van Laere, Eyetronics scanning technician, recounts that scanning the notoriously cantankerous zebras can be dangerous. If you are standing behind a horse, it can kick you backwards, but zebras can kick not only to the back, but also to the side. Theyre genetically programmed to fend off lions and other predators in the wild, so it was pretty scary to scan them. All of the animals horses, zebras, a goat, a pelican and a dog were accompanied by a trainer to keep them quiet and under control. Early on in the scanning process, some of the animals reacted to the camera flashes, but soon grew accustomed to the situation. To capture optimum scan data, the animals had to stand as still as possible. This posed challenges for some of the animal cast. A large black horse had been in training to nod his head for two weeks. In spite of the trainers best efforts, the horse thought it was supposed to nod and eagerly did so throughout the entire session. Another horse had been trained to lean up against a wall and was intent to get to a wall to perform his task. The two horsefly maquettes were perfectly behaved, however!

Racing Stripes was a great exercise of our 3D scanning capabilities, added Tesi, and were looking forward to more animal scanning in the future, whether its in a barn, on set or in another exotic location.

Like all films with intense visual effects needs, Racing Stripes pushed Hatch and his team with challenges that proved daunting at times. One of the big challenges was during the nighttime Blue Moon race, where we were recreating a lot of horse breath and whiskers. Clydesdales have all these hairs on their chins, so all of that to be removed and then recreated and put back onto the talking mouths. But really, meeting deadlines was the ultimate challenge, Hatch laughs. We were about four weeks out and we still had roughly 400 shots left. They were all in various stages, but it was tough. We wanted to give everyone the most flexibility as possible, so a lot times the dialogue changed dramatically from where it started. A lot of lines were rewritten to be funnier. We would get three quarters down the road on a dialogue scene and wed have to go back and rework it. But if we had to go back to the standard way, we would have never accomplished it, so the technological breakthroughs were really great.

Plus, the 3D tracking software has gotten so much better and it made a huge difference. And it also helped that Alex Williams was the animation supervisor and he brought in a whole new way of looking at things. A lot of 3D artists are up on 3D animation, but they dont know the classical style. With the volume of the squash-and-stretch for the mouth movements, he brought in hundred and hundreds of drawings to show what the mouth shapes should look like and these types of drawings were extremely helpful. We also took video of the voice actors so that we could look at them to get their movements and bring that acting into the animation.

Assessing Digiscopes most important contributions to the film, Hatch offers, I think the thing that we brought to the table that was different, was developing the technical process and then a lot of the matte paintings, Hatch continues. Frederik had ideas of what he wanted and overall he wanted more of a fairy tale look for the film and we originally started more realistic. But he would allow us to go ahead and mock up things, like the Blue Moon race sequence. He directed us more into his aestheticbut he has very good taste and is very patient.

Tara DiLullo is an East Coast-based writer whose articles have appeared in publications such as Sci Fi Magazine, Dreamwatch and ScreenTalk, as well as the Websites atnzone.com and ritzfilmbill.com.