In celebration of Black History Month, Martin Goodman chronicles the rise of positive representations of African-Americans in animated shows.

The year was 1832, and Thomas Dartmouth (Daddy) Rice was one of Americas hottest acts. His performance was not a spectacular one, nor was it entirely original; the material it was drawn from had already existed for a decade or so. Rice, however, added an odd little dance to it, and took on an old name that would resonate throughout America for more than a century. With burnt cork smeared across his face (save for a wide swath around his lips), Rice Jumped Jim Crow for an ecstatic audience in New Yorks Bowery Theater. Thereafter, blackface minstrelsy blazed its way across American popular culture. Two years later another white performer by the name of George Washington Dixon took the stage in the persona of Zip Coon," a dandified black wise fool." For the next 70 years the minstrel show would be a predominant feature of the nations entertainment. It would also define and codify the role of blacks in an art form not yet invented -- the American animated cartoon.

The eye-rolling, wide-lipped coon came on to the animation scene along with India ink and rice paper. He did not leave for a very long time. In some cartoons his image was stereotyped to the point of reprehensibility; in other cartoons, such as Bob Clampetts Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs (1943), the stereotypical presentations existed alongside other codes and possible interpretations that are still being strenuously debated today. Whatever the case, every black character in cartoons, both male and female, was a direct descendant of Jim Crow, Zip Coon, and Old Aunt Jemima (who dates back to a blackface performance of 1889). Even much of the music that accompanied their on-screen appearances was originally composed by Stephen Foster, perhaps the greatest writer of minstrel songs that era had ever seen.

However, thats not what were going to discuss. There have already been several masterful books written on the subject of racial stereotyping in film, animated cartoons, and radio. For this special piece to accompany the celebration of Black History Month, we will examine how the old stereotypes in American animated cartoons were replaced by positive, intelligent, even activist representations of African-Americans over time. This month we will look at who moved in to the animated world after the minstrels left town.

The first occupant was actually seen in an educational film sponsored by the UAW-CIO and produced by United Productions of America in 1946. Brotherhood of Man was a stylish animated short intended to help union members in the southern United States overcome their racial disharmonies and band together as brothers in labor. In this film, highly stylized but clearly identifiable members of each race learn that underneath their skins their only true differences lie in blood types. The message as delivered is somewhat simplistic, yet there is undeniable uplift in the shorts final scenes. Men of all races, liberated from prejudice, march off to work together as the narrator delivers a stirring speech about equal opportunities for all.

From 1950-80 it was evident that America was changing rapidly, and so were portrayals of African-Americans. Even cartoons, still considered by most critics to be a juvenile form of entertainment, were affected. During the 1960s the Civil Rights movement won significant victories under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the accordant political muscle of President Lyndon B. Johnson. It would no longer do to have African-Americans depicted as descendants of minstrel shows, and such images began to be excised from existing theatrical cartoons. It would also not do to have black characters as token sidekicks or peripheral hangers-on in television shows. Black characters would have to be co-stars at the least, with starring roles even more optimal.

It didnt happen right away. Animated shows on television dated back to 1949, but it was not until 20 years later that the first African-American character made his appearance. Comedian Bill Cosby worked alongside animator Ken Mundie to bring his creation Fat Albert to life for the television special Hey, Hey, Hey, Its Fat Albert! More would be heard from Cosby later, but in 1970 the first black cartoon star would premiere with an effort that paralleled the difficulties that African-Americans were facing in larger society.

Bill Hanna and Joseph Barbera wanted to adapt the popular comic book Josie into a cartoon about a rock band. They also hoped to form a live rock band that would sell hit songs from the show. La La Productions, run by Danny Janssen and Bobby Young, were in charge of the recordings. They held a contest in order to find singers who resembled the girls, but after they did, there was a slight problem. In the comic books, Valerie Brown was a beautiful black woman, but H-B reportedly wanted an all-white trio. Janssen battled the studio until he won; Valerie (and her singing voice, Patrice Holloway) was the first black cartoon star. A smart, talented, and level-headed counterpoint to ditzy Melody, Valerie Brown refuted every cartoon stereotype about blacks that theatrical cartoons had perpetuated for decades.

Valerie Brown did not refuse to give up her seat on any bus or doggedly camp at any lunch counters. She was not escorted to school between two grim rows of National Guardsmen, nor did she riot in the burning despair of Watts. Valerie Brown did not give any speeches about having a Dream, nor pump her fist into the air while standing on an Olympic medal platform. Political power did not come through the barrel of her gun, and it is likely that she never thought about owning one. No matter; Valerie Brown was a proud figure in African-American history as it related to popular culture.

When Josie and the Pussycats first appeared on CBS, they were followed on that same day by animated versions of the Harlem Globetrotters, who had been given their own cartoon. Thus, September 12, 1970 is a momentous day in the history of integration (if only in the world of Saturday Morning cartoons). Later in 1970, the first originally written black character appeared in animation. The short-lived CBS prime-time series Wheres Huddles? featured a football player named Freight Train, who was the best buddy of the white star of the show. There was no mistaking these characters for any that might have appeared in American theatrical cartoons of the 1940s.

The following year brought more changes. As rock and roll music continued to percolate into the animated television show, popular bands that appealed to the younger set were caricatured in cartoon form and transported to Saturday Morning. Thus, ABC brought audiences The Jackson 5ive in 1971. The titular brothers (featuring a young, pre-surgically altered Michael) traveled the globe as musical ambassadors, singing their platinum-level hits. Minstrels they were certainly not. 1972 saw one of our most famous black athletes get his due when Willie Mays portrayed himself in the ABC Saturday Superstar Movie Willie Mays and the Say Hey Kid.

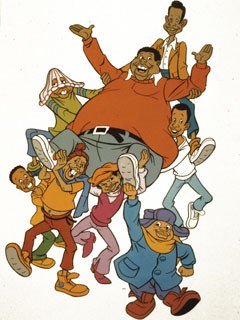

Fat Albert, in the meantime, had not disappeared. Bill Cosby brought him back, along with a supporting gang of pals, in Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids in 1972. Again, CBS proved itself committed to continuing the integration of Saturday Morning. This is an important note, since Fat Albert was in many ways a very risky show. At a time when racial tensions were still running high, less than 10 years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Cosby dared to tell it like it was. Although the kids were decent at heart, Fat Alberts cohorts were truly a gang, living in a ghetto environment and constantly tempted to do the wrong thing. Cosbys gentle moral lessons kept things in perspective, but there was little sugar-coating to be found. In later years, the gang would even be transported to a prison to be Scared Straight by savage inmates following a minor transgression.

After Fat Albert appeared, the integration of blacks into American animation progressed at an increasingly rapid rate. Sealab 2020 featured a black scientist. Had any of the characters from Walter Lantz 1941 shorts Scrub Me Mama with a Boogie Beat or Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B showed up on these Saturday Morning cartoons, they would have seemed so anachronistic and ridiculous that Valerie Brown would have wept in shame. Black characters were now intelligent and competent, and no one could call them token players. When involved in humorous situations, they were neither the butt of racist gibes nor portrayed as gaping, superstitious fools.

The majority of the changes were seen on network television; except for Disney animation, feature films were fallow ground and no significant changes occurred, save for the films of Ralph Bakshi. Bakshi, it will be recalled, presented African-Americans in a new (if hardly flattering) light. Through films such as Heavy Traffic (1973) and Coonskin (1975), Bakshi channeled a vision of a harsh, urban world beset by crime, violence, and characters (both black and white) drawn from his own rough boyhood. Ralph Bakshis animated African-Americans were no servile clowns or dice-tossing Sambos; indeed, they would kill any fool who tossed a racial epithet their way.

If there was a common theme to Bakshis blacks, it was that of unrest and bitter dissatisfaction with their environment. Although the anger and alienation in his characters may have been portrayed accurately, there was little that was positive about them. Bakshis characters seemed to represent the views of Malcolm X, with more nihilism thrown in. Most African-Americans found Bakshis depictions reprehensible. Still, Bakshi never dealt in old, antiquated stereotypes; many of his black characters delivered a genuine fury to the screen that pointed up integrations problems and failures, as well as the persistence of racism.

Today there are few cartoons (especially those in an ensemble format) in which African-Americans are not featured prominently, and it is difficult to foresee a future in which this will not be the case. Entire animated series such as Little Bill (1999) and The Proud Family (2001) featured the daily lives and dilemmas of African-American families. There are now so many entertaining black characters featured in so many cartoons that it would be onerous to list them all. From Arnolds good friend Gerald Johannsen to Kim Possibles brilliant tech support specialist Wade, African-American animated characters have become stars in a way that was not possible as recently as 1970. If American society had integrated half as well, UPAs Brotherhood of Man might have been totally achieved by now.

Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman is a longtime student and fan of animation. He lives in Anderson, Indiana.