Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman chronicles the long history of animation colliding with celebrity in this month's column.

Animation and celebrity have a long mutual history. As far back as 1916, when the art form was younger than Angelina Jolie's latest adoptee, Kinèma Exchange produced films featuring "Charles Chaplin." The merry tramp was soon joined onscreen by animated depictions of contemporary comedian Ben Turpin. Animation and the public perception of celebrities began to evolve together. There was something endearing about seeing beloved entertainers caricatured, and virtually every studio tried their hand at it.

Some celebrities seen in Warner Bros. cartoons had more appearances than some of the studio's animated characters. Jack Benny appeared in eight Warner Bros. cartoons, W.C. Fields nine, Eddie Cantor 11. Laurel and Hardy were in 10 shorts. Jerry Colonna appeared in an even dozen, the same as Bing Crosby and Jimmy Durante. Cartoons, such as The Coo Coo Nut Grove (1936) and Hollywood Steps Out (1941), featured a gala of Tinseltown's elite. One charming effort, The Woods Are Full of Cuckoos (1937), caricatured Hollywood stars as animals.

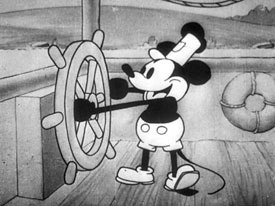

Disney enjoyed producing shorts during the 1930s that typically featured Hollywood luminaries as storybook characters (Mother Goose Goes Hollywood, 1938), or as toys (Broken Toys, 1935). Often they joined Mickey Mouse on screen, as Mickey was a bonafide celebrity himself (Mickey's Gala Premier, 1933; Mickey's Polo Team, 1936). The Fleischer studio also animated celebrities, though less frequently.

In every animated short (with the possible exception of Bingo Crosbyana, 1936), these celebrities were loved. Their physical features and personal foibles were the object of gentle gibes; good-natured pokes that stars might take from their best friends. As we know, Hollywood was rife with promiscuity, addiction, infidelity and other miscreant behaviors for all of its history. The very people animating these short films were among the most aware of these facts, but racy innuendo was stringently off-limits. Publicizing any star-related scandals would have hurt very valuable studio property. Such disclosures would have also counteracted the work of studio publicity agents, who put out countless fires and were often a star's first line of defense.

The same was not true outside of the studio system. Gossip specialists, such as Louella Parsons, Walter Winchell and Hedda Hopper, wielded a mean axe throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Bereft of a cell phone/camera, text messaging capacity, broadband connections, or anything in the media-heavy arsenal that a Perez Hilton possesses, these columnists were able to dig up amazing amounts of dirt on the stars. Many a Hollywood heavy lived in perpetual fear of those journalistic jackals, the forerunners of today's paparazzi.

The scandal sheet dates back to 1916 with Stephen G. Clows' tabloid Broadway Brevities. In later years, magazines such as Confidential, Dare, Whisper and Uncensored titillated the public during the 1950s. Allegations of affairs, crimes and same-sex liaisons among the stars were bandied about with gleeful abandon, keeping publicity agents -- and lawyers -- busy souls indeed. Informants for these magazines often consisted of private investigators, call girls or even rouge publicity agents copping a buck on the sly. Nothing on any website or blog today could match these drugstore smear sheets in terms of mean-spirited ferocity, and they were widely read. Nowhere in the world of theatrical animation could similar sentiments be expressed.

Nothing in any studio would go beyond caricatures of Clark Gable with elephantine ears, Greta Garbo with gargantuan feet or the comical situation between Eddie Cantor, who had five daughters, and Bing Crosby, who had four sons. Warner Bros. continued to produce such harmless films throughout the 1950s (Jack Benny was a favorite guest).

In short, as long as animation was tied to the studio system and used as theatrical filler, it was unlikely that any star would suffer humiliation in any cartoon short. Disney's independence meant that they were free to take such shots as they wished, but the studio was concerned with presenting a clean image and, by the 1940s, was pretty much done with depicting celebrities in any case. Their last such extravaganza was the Donald Duck short, The Autograph Hound (1939).

With the demise of the Hollywood studio system around 1960, the greatest stars in the world were free agents and major targets. No studio spin doctors were there to soften the blows, and the tabloids began a field day. The romantic imbroglio concerning Elizabeth Taylor, Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds, which began in 1959, consumed enough ink and paper to deplete the world's existing resources. When Liz dumped Eddie for Richard Burton in 1964, it is likely that the deforesting of the Amazon also began at that point. (Note: For those of you not familiar with this chronology of spouse-stealing chicanery, ask your grandparents; I have a word limit. You'll know what I mean when your grandkids ask you questions like who "Bennifer" was. -- Dr. T.)

Such a scandal today would have been par for the course, but in those days the tabloids aimed and fired at the cuckolds with the print equivalent of nuclear warheads. Without competition from TV shows aimed exclusively at slavering over celebrities or armies of savvy bloggers, these magazines tripled in proliferation. Today they are joined by several television shows, such as Entertainment Tonight and Extra, which dwell on all possible minutiae of celebrity lives, while providing vital information to the public, such as which syllable of Demi Moore's first name should be properly stressed.

As for animation? Celebrities, in truth, largely disappeared from the scene. As Hanna-Barbera began its nearly uncontested ascent to Saturday morning supremacy, the studio concentrated on its own cartoon celebrities, such as Huckleberry Hound and Yogi Bear. A few stars did drop in from Hollyrock on The Flintstones, and there was also that animated embarrassment known as The New Scooby-Doo Comedy Movies. You may safely bet that the celebrities depicted therein were better behaved than the kids watching.

Once in awhile Steven Spielberg would caricature a celeb or two in his Animaniacs cartoons, but the tweaks were as harmless as the ones seen in the classic Warner Bros. cartoons that Spielberg so loved.

It wasn't until 1998 that animation began locking its sights on Hollywood's hallowed with an aim to maim. Celebrity Deathmatch was an MTV production, headed up by Eric Foge, that featured the famous walloping and killing each other in bouts of mortal combat within the squared circle. This clay-animated exercise in mayhem had its own weird continuity, scads of pop-culture in-jokes and a few disembowelments and beheadings thrown in for laughs. Poking fun at celebrities was one thing; having them viciously rend each other to pieces was quite another. The series is now in its second incarnation. It had taken several decades, but animation and popular culture finally intersected in their intrusive, often savage obsession with America's celebrities.

The rock music scene was not immune to the new wave. Web-based productions, such as Behind the Music That Sucks at Heavy.com, use cutout animation in order to throw heavy gibes at today's most celebrated musicians. A parody of the VH1 series Behind the Music, this caustic but comical series managed to outlive the original and is still running today. It does not seem to be coincidental that Dave Carson and Simon Assaad launched Sucks in 1998 -- the same year that Celebrity Deathmatch premiered on MTV.

This brings us to Where My Dogs At?, a short-lived series produced under the rubric of MTV2's Sic'Emation. Although this show seems to have ended last summer, it made a significant statement about how animation progressed in its perception and presentation of celebrities. The mock disclaimer at the beginning of the show assures us that while "No animals were harmed in the making of this cartoon, many celebrities probably were." The disclaimer is only half joking.

Where My Dogs At? is superficially the tale of two stray dogs on the mean streets of Hollywood. When not avoiding a dogcatcher whose face is too hideous to be shown, they become entangled in the lives of today's most lampoon-prone celebrities. Some are longtime stars, while others are recognizable only to that generation who boast every communication and media device known to civilization. While this concept sounds like 2 Stupid Dogs Go to Hollywood, Buddy and Woof are rarely central to the plot; they are rather the device through which celebrities are scourged and scoured by creators Aaron Matthews Lee and Jeffrey Roth. It is no accident that Lee and Roth have both served as writers on many music and film awards shows and celebrity roasts.

Where My Dogs At? is unsparing in its depictions of addictions, sexual misbehaviors, and psychiatric disorders of the stars (including that relatively new genre of untalented people who are famous for basically nothing). Dogs cuts across the spectrum of film, music, and pop-culture stars with one hand keyboarding Flash and the other hand turning the pages of The Hollywood Star and The National Enquirer. Watching this show is akin to watching a shooting gallery in action, even if some of the targets seem rather deserving. The age of respect and gentle chuckles is over, and the price of stardom is higher than ever.

Not only can a star now be instantly caught in any conceivable indiscretion, but the deed can be transmitted around the Web and other modern media within hours and there is no way to control the damage. Thanks to the speed and versatility of Flash animation and other programs, the same information can be turned into an animated cartoon within a day or so. Matt Stone and Trey Parker have been proving this for some time now with South Park, and the rich and famous are going to make for some great animated entertainment in the future. The type of entertainment provided, however, could never have been foreseen by Jack Benny, Jerry Colonna or Jimmy Durante.

At the time this column was being researched and composed, Anna Nicole Smith was found dead in a Florida hotel room, and the media blizzard continues unabated. Ms. Smith gained renown for very little besides a May/December marriage followed by an unending court battle, and, later, for basically walking around as a caricature of herself on reality TV. It may be some measure of her fame that, while Anna Nicole never made to Where My Dogs At?, she did defeat Sarah Ferguson in her only bout on Celebrity Deathmatch.

Martin "Dr. Toon" Goodman is a longtime student and fan of animation. He lives in Anderson, Indiana.