Richard OConnor takes an extensive look at the animated films of Michael Sporn, available on a first volume DVD of the animators work.

John Hubley would record and edit a complete soundtrack before beginning production. Not just the voice track, the music as well. Once asked how he could tell if the audio would make for a good film, he replied, If the soundtrack works and its good, the picture will be good. Michael Sporn began his professional life in the Hubley Studio; he clearly absorbed the care for the voice track a sensitivity to performance that can alone carry a film.

A motion picture, as is music, is a performance-based art. A cheap and wooden showing from an actor obscures the rest of the picture beautiful photography goes unnoticed, sterling script lies butchered. An inspired performance transforms a lackluster film into an extraordinary experience. Ignore, for now, that good acting on film is often the result of good editing, its the results that are important. The human connection linking the spectator with the screen is made through the conduit of the actor.

The animator has two opportunities for mucking up a performance. A shoddy voice track will wreck an otherwise outstanding piece. Or a workable record can be devastated by awful acting in the animation.

After working with Hubley on short films, segments for The Electric Company and a feature length television special for CBS, Sporn headed the New York department of assistant animators on Richard Williams Raggedy Ann & Andy and was the producer/co-coordinator/assistant director on the PBS Christmas Special Simple Gifts. By 1980, Michael Sporn Animation was established. An Academy Award nomination followed shortly thereafter in 1984 for Doctor DeSoto, written by William Steig.

While the 80s may be remembered for Princes Purple Rain, Thierry Muglers geometric fashions, and corporate Americas fusion of advertising and animation on Saturday mornings, Sporns work moved toward the organic and the literate. He created a string of warm, textured, gentile films. Some Abels Island, The Red Shoes, The Marzipan Pig are overlooked gems. His production process was an extension the independent movement of the 60s and 70s, shouldering much of the work himself, then hiring fledgling artists to work with veterans to help stretch the finances. Despite his retiring nature he became a central figure in independent animations revitalization in the 90s through a regular output of quality childrens films and his cultivation of young talent.

Following a form set by Hubley in films like Dig and Everybody Rides the Carousel, Sporns films mix career actors with non-professional voice performances, often by children. The voice tracks have a directness and an honesty, while the music in his films may not soar to the heights of Quincy Jones music for Hubleys Eggs, thats a bit like complaining Mahlers Eighth doesnt stack up to Beethovens Ninth.

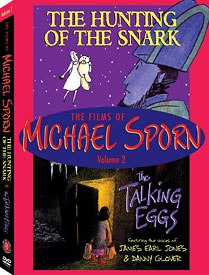

Sporns work has been released over the years in a handful of VHS editions by Family Home Entertainment, Scholastic and others. Some films are available with material from other animators in issues from his clients, most notably HBOs Goodnight Moon (one of several specials for which he created short pieces) and WGBHs Between the Lions. First Run Features release of The Films of Michael Sporn constitutes the debut of DVDs devoted exclusively to his work. Two separate disks each contain two films with commentary tracks, additional artwork, and a short live-action Making of documentary.

Most of Sporns work has been on commission. He explains this on each disks Making of documentary. Works on commission generally fall into two categories (with many happy exceptions): garbage and unworkable garbage. Oftentimes the foundation of a commissioned piece is so fabulously flawed, no manner of filmmaking genius can build a solid picture. Two of the four pictures released on First Run Features DVD issues of The Films of Michael Sporn are works for hire, and they clearly suffer for it.

Whitewash was commissioned by HBO in 1994. Based on actual events concerning a young black girl painted white by a gang of thugs, the story is an easy platform for the type of simplistic moralizing favored by broadcasters. To his credit, Sporn avoids pandering to easy, feel good positions. Instead of pontificating on bigotry, Whitewash plays up personal reactions to the crime: the young heroines transformation from outgoing confidence to dejected isolation, her brothers need to make the crime about him (Yeah, like I aint hurt too.) a smart insight into human character, how many people in Peoria, for example, will obsess over their personal tragedy in the destruction of the World Trade Center; the brothers uncomprehending bravado (Did you see me, Nana, I was on TV?); her classmates overreaction (I think there need to be more security guards.). These are real human reactions, not common educational tropes on togetherness and cooperation.

The script produces a few cringing moments, nonetheless. Believe it or not, the heroines grandmother actually calls her chile and the film ends with a hip hop number just before the credits begin to roll. This last offense smacks of such immense tastelessness, it feels as though this is reason Sporn was so quick to mention the commercial nature of the work.

The other commissioned film of the set, The Talking Eggs, was produced in 1992 for WGBH, Bostons PBS affiliate. Here, again, the location is the inner city and a story, which could be presented in stark and simple contrasts, is instead told with depth and sensitivity. Also, an older black woman refers to the young heroine as chile.

The disclaimer, based on a folk tale is great big warning sign: beware of nonsensical fantasies, moralizing and a possible deus ex machina. The setting is relocated from the folk tales Southern bayou to the Bronx. In The Talking Eggs, the stark good or bad characteristics of folk tales are given shades and motivations. The mother, set up as a villain, insists her daughter cook and clean at the expense of childhood pleasures. She is shown as single mom raising two children and working to provide for them. When a fantastic solution to their financial problems presents itself, she does what most of us would do. Realistic actions are shown in a reasonable way regardless of the incredible situation.

In the Making of documentaries Sporn talks about designing films with a 20th century look opposed to a 19th century look of most animation. His terminology is charged, and not really accurate big eyes and wide thighs in Burne-Jones? A crosshatched Fred Flintstone? but his meaning is clear. He intends to produce forward thinking films in the tradition of UPA and John Hubley. He aspired to pull visuals from the contemporary graphic lexicon, not the work of other artists from three generations ago. The design of these films is more of drawback than an asset. The linework is typically flaccid, the color tends to be messy and the backgrounds are often overpowering or inappropriate. The attempts are interesting, but ultimately fall short. Part of the designs failure rests on the work for hire issue.

Making someone elses film, whether contracted by a Hollywood studio, advertising agency or broadcast network, asks creative devotion in exchange for financial reward. The financial reward for short animated films of this type is notoriously small. Executing the art styles chosen for these films is an extraordinary expense. To achieve the texture in design of The Talking Eggs the production artists had to color on paper, cut to the line and mount the drawing on acetate. The shading needs to be followed through in art production so that it doesnt pop and draw undue attention to itself. The entire process is more time consuming (and hence more expensive) than cartoon painting.

To make up for this added expense, he takes animation shortcuts. Fewer drawings means less art production, which means the job can be completed on budget, which means everyone gets paid, which means a few less animators shaking cans on the subway. Here is the great tragedy in many of Sporns films, the animation itself isnt that good. Not that its limited, limited animation is inherently no worse than full animation. In The Talking Eggs and Whitewash, the limits to the animation are obvious and unattractive. When a characters head is broken from the body in a cartoon the match line is easily hidden: the animating face is a flat color and the held cel is a flat color. With the shaded and textured approach, when the face moves on a still body the seams will show. Attention gets drawn to the limited animation because the styling doesnt allow for typical cartoon short cut.

Sporns shortcuts sometimes work, as in Whitewashs dream sequence in which the brother sees the attack in monochrome with animation on holds and dissolves and, in the same film, the grandmothers recollection of life in the South using similar techniques. These are the inspired moments in his films.

Some animators work succeeds on emotion (the great Disney animators Milt Kahl, Bill Tytla are obvious examples). Sporns strength is his brain. When he uses intellect to solve a scene and not rely on bravura animation, the scene works. Animation is all turns and blinks or powerfully gesticulating arms, knowing just what to show. In The Hunting of the Snark, Sporn shows his stuff as an artist. Based on Lewis Carrolls mock epic poem, The Hunting of the Snark is a beautifully animated, lovingly rendered piece. The film was made over the period of several years, produced in between commercial projects. Given the proper time to produce the picture, the proper results show.

The storyboard was created in a few whirlwind days and executed without revision. Energetic, spontaneous, slightly imperfect, slightly loopy visual storytelling paralleled with smart, energetic, spontaneous animation all anchored by James Earl Jones assured narration.

Visually, The Hunting of the Snark conjures a look similar to William Steig or Peter Arno faux naïve drawing verging on cartoon but sophisticated enough to be under The New Yorker masthead a look in synchronization with the layered maturity of Lewis Carrolls text. Seven characters, the Bellman, Boots a maker of bonnets, a Barrister, a Broker, a Beaver, a Baker and a Butcher (the alliteration of the B allegedly stems from a game Carroll devised to overcome a childhood stutter) hunt the oceans and the islands for the mythical snark. As the story takes us through the ocean, the dead of night, the mens dreams, the visuals shift and dance with the same lighthearted ease of the text.

Like many of Sporns films, The Hunting of the Snark is an in between film. He recounts the story of screening where the parents were near outrage. They couldnt understand it. What did they find? What happened? A turned their questions over to a younger audience member who answered: these guys when on a hunt and found a monster. A simple, correct answer, but lacking.

Lewis Carroll evaded questions on the meaning and nature of his work. Sporn interprets the material as if its The Canterbury Tales, each player is given a turn and the story as a whole is presented with straight-faced dignity. The presentation assumes either an intellectual sophistication to interpret the imagery or a youthful willingness to accept without question. To accept the tale on face value, you get a near nonsensical quest for an unseen prey. You get a beautiful looking film thats easy on the ears. But theres more going on. It falls in between the easy answers of childrens films and the obscurity of standard art film fare.

Sporn animated the entire film himself over the course of several years and the animation deserves special note. Each of the seven characters usually acting in pantomime has a distinct personality. Examine nearly any scene to find simple economic ways of doing beautiful animation: a 12-frame hold animates in two seconds to another hold into another pose, the camera dissolves and trucks, artwork judiciously reused, and characters occasionally move into silhouette.

The fourth film of the set, Champagne, a documentary, succeeds on the charm of its eponymous star and narrator. Its faux urban design reflects the same intentions as The Talking Eggs and Whitewash. Champagne recounts the story of her young life. She lives in a convent (its called My Mothers House, but when you live in a house of nuns youre living in a convent) having been placed there by her elderly grandmother after her drug-addicted mother was sent up the river for murder. Champagne tells all this with matter of fact coolness. Her nonplussed aplomb, peppered with bits of teenaged humor, creates a shell of warm intimacy in film.

Champagne, in a word, is personable. Champagne is also a solid piece of filmmaking, free of sentimentality but full of affection. While it may suffer from the same stylistic drawbacks of The Talking Eggs and Whitewash, it is buoyed by a star turn performance from Champagne.

Champagne, The Talking Eggs, and Whitewash essentially share the same world. The urban landscapes, the underdogs, the similar visual approaches bind the films together on the surface. They share similar stylistic setbacks in their animation. They also hold the same solid foundation of effective storytelling and they all have anomalous in animation sincerely insightful treatments of their main characters, insight which reflects real human experience. These three stories emanate from a like perspective: the observer, affection from a distance. While that allows for even-handed storytelling and dispassionate character study, the urgency, the vitality of something like The Hunting of the Snark goes missing. These efforts remain infinitely more rewarding than the standard cartoon fare of gross-out retreads or PBS educational do-goodisms. They straddle the precarious edge between commercial and independent animation. The Hunting of the Snark, by contrast, reveals the shortcomings of this area. It is a wholly original world, the kind of experience you can only hope for in fantastic film.

The Films of Michael Sporn, Volume 1 (57 minutes) and Volume 2 (68 minutes). DVD. $19.95 (each volume). Available at www.firstrunfeatures.com

Richard OConnor likes to tell other people how to make movies. He has done this at Parsons School of Design, NYU, in numerous magazines such as ASIFA International and Boards, and at animation studios throughout New York including his own recently founded Asterisk.