In the second of four installments on art direction for their book Inspired 3D Short Film Production, Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia look at how color, texture and style help define characters and story.

Stop-motion master Henry Selick brings the color to The Life Aquatic with his creatures. All The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou images © 2004 Buena Vista Pictures Distribution. All rights reserved.

Henry Selick makes stop-motion animated films. The concept is not shocking. But just try explaining it to your nine-year-old nephew, whose computer is probably faster than yours and who knows how many effects shots there were in Attack of the Clones. Stop-motion is trés hip to those in the know, but to the general public it barely registers. Yes, The Nightmare Before Christmas rocked, but that was 11 years ago. Chicken Run was a hit, but most people probably think Aardmans plasticine models were CG. And some prominent media personalities already think that Selicks stop-motion fish creations in The Life Aquatic, which opens nationwide this week, were just sloppy computer work. (A.O. Scotts critique of the films computer-animated fish in his New York Times review is a grim reminder that you dont have to start with the press kit, and you dont have to end with it, but reading it is more than good manners.)

In our all-digital modern age you can count Hollywoods big-screen practitioners of stop-motion animation on two thumbs. I mean, stop-motion? What the hell? They didnt have that elective in college. Simply put, theres no explaining Selicks career choice. Its like radio drama. Nobody does it. Except the people who do it.

Its a niche thing, and Wes Anderson, director of Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums, knows niche. In The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, his latest film, which he directed and co-wrote with Noah Baumbach, Anderson exercises his eccentricity underwater, and Selick has come to his aid with his beautiful and incongruously analog brand of animated critters.

The Life Aquatic is Andersons fourth feature, and his third under the aegis of a sweet indie deal at the very un-indie Disney Studios. Bill Murray plays a has-been oceanographer named Steve Zissou whos been pumping out underwater documentaries for decades and is about to call it quits. He is joined on what may be his last mission, a quest for the dreaded jaguar shark, by his wife Eleanor (Anjelica Huston), a magazine reporter (Cate Blanchett), a needy underling tired of being on the B-team (Willem Dafoe), his long-time financier (Michael Gambon), a rival oceanographer (Jeff Goldblum) and a pilot who may also be his long-lost son (Owen Wilson).

Naturally most of the film is spent in close communion with creatures of the sea, and all the fish odd and beautiful enough to earn a closeup were created by Selick and his team of stop-motion animators. Anderson chose animation for the practical reason that his sugar crabs, pony-fishes and paisley octopi dont exist. He chose stop-motion animation, and Selick, for more poetic reasons: Like Anderson, Selicks aesthetic is old school.

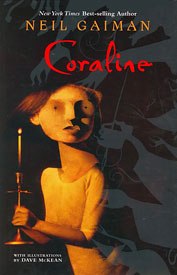

Selick has had no end of work lately. Since joining Vinton Studios in Portland, Oregon, this June, it was announced in September that Selick would direct a feature-length version of Neil Gaimans best-selling childrens book Coraline, a Vinton co-production with Bill Mechanics Pandemonium Films. Coraline is a supernatural thriller about a young girl, a locked door and the looking-glass world of danger on the other side, and has a tendency to grab readers and make them devour its 162 pages in one two-hour sprint to the finish.

Then this October, the trades reported that Anderson would make a stop-motion version of the Roald Dahl classic The Fantastic Mr. Fox for Sonys Revolution Studios. The 1970 favorite from the author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory details the adventures of Mr. Fox as he goes up against three unpleasant farmers in an attempt to feed his family. One name springs to mind for a prospective animation director for the film, but is Selick actually attached to the project?

Selick discussed this and other topics this week in a chat with AWN, touching on The Life Aquatic, his upcoming feature projects and his upcoming short subject Moongirl. First, though, he teased with a new factoid regarding one of his earliest film credits, Twice Upon a Time, a 1983 animated feature directed by John Korty and produced by Alan Laddie Ladd Jr. that still hasnt made it to DVD.

Henry Selick.

Henry Selick: I have another connection now to Alan Ladd Jr., because the producer Im working with, John Carls Ive known him for years and I never realized that hes married to Alan Ladd Jr.s daughter.

TJ: Thats a crazy bit of Six Degrees.

HS: So basically I want to go to John were developing a project and see if Laddie can get behind a big DVD push or something to get [Twice Upon a Time] out again. Id love to re-cut the darn thing.

TJ: I would love to see you re-cut it. Tell me about how you first met Wes Anderson. Did he call you up because of Life Aquatic or because of Fantastic Mr. Fox? And are you even attached to Fantastic Mr. Fox? The information in the trades is a bit ambiguous.

HS: Its sketchy in the trades, but he first approached me through Michael Siegel, who represents the Dahl literary estate. I know him from having worked on James and the Giant Peach. And Wes approached me and talked about Fantastic Mr. Fox, and then it was more a segue into By the way, theres another movie Im doing first, Life Aquatic. That was a while back, like two years ago. Then many, many months went by and I finally had my first meeting with him, and we talked about why he wanted stop-motion creatures in Life Aquatic. I myself had a lot of doubts, because he really wasnt that familiar with stop-motion. Hed seen my films. I dont know if hed seen a Ray Harryhausen film. So I approached it cautiously, because I didnt want to start doing the work and then have Wes realize Hey, this isnt real! Whats going on? Its hurting my movie! But I give Wes credit, hes a true visionary.

TJ: How much of Andersons work had you seen before he talked to you?

HS: Id seen Royal Tenenbaums and Rushmore, and both films, I think, are brilliant. I hadnt seen Bottle Rocket at the time. But I knew the moment I saw Rushmore when I saw that film, I felt a strange connection. I thought he was incredibly talented. For me, at that time, that was the best role I thought Bill Murray had ever had. How Wes handled Jason Schwartzman, and just the handmade quality to things, the artifice, the acts, the curtains and all. I really fell for it. Ultimately thats why Wes wanted stop-motion. He likes to hand-craft his films. Hes not flying his cameras around all the time. He would always rather build something for real than do it with CG or composite models.

Selick helps create a baroque artifice for The Life Aquatic world.

TJ: That is the beautiful thing about his work, that wonderful baroque artifice. Even the intertitles are scrunched up incredibly close to the edge of the screen. He wants you to notice that proscenium edge.

HS: I wasnt over there in Italy I went to visit him before he started shooting the film, it was primarily shot in Italy at sea and on stage at Cinecitta, and he was very, very precise about color, camera placement, everything. And its beautiful. It does add up.

TJ: Did Wes and Noah come up with names for the fish, or did he let you go wild and then insert your fish names into the screenplay later?

HS: We never went wild for what creatures were going to be in there. Theres a few creatures that, design-wise, we were pretty much given free reign. But he always had a certain idea of what the fish had to deliver. The crayon pony-fish, that colorful seahorse, was written to be a seahorse with crayon colors. So theres always a good starting point. The sugar crabs were meant to be pretty realistic crabs that happen to look like candy. So in most cases, the original idea was his.

TJ: I know some fish in the screenplay didnt make the cut. The rat-tail envelope fish made the trailer but not the film. And the screenplay mentions a bright red octopus in the scene with the submerged plane. Did that get made?

HS: It got made. It got made to fly out of a window. Originally they went inside the plane and there was a sea scorpion, but the whole sequence got trimmed. The movie was running long. Those exist. And the octopus, we made it a paisley-colored octopus.

TJ: You can see the octopus on the Life Aquatic bus shelter ad, right?

HS: Yeah. And its in the background of another shot. Its just in there in a subliminal way.

TJ: What were the creatures made of?

HS:

The traditional thing is metal armatures and foam latex they call it Schram but in most cases we still use metal armatures as the skeleton, and then we use this type of silicone called Dragon Skin. Its in a lot of new toys, human prosthetics people whove been in a war and half their face is missing. They make prosthetics that are incredibly lifelike and fleshlike out of this stuff. So thats what we used for body and skin.

TJ: Has anyone used that before in animation?

HS: Were certainly among the very first. We may not be the first, but its just happening now. Its a brand-new idea. In the past, silicones were the rule, but theyre too heavy. You couldnt paint them. They wouldnt take color. And they only had so much give before they would tear. This new stuff is phenomenal. Its very, very elastic, and it takes the color well. The only downside is its pretty heavy compared to the foam, so you have to hollow things out, build inner shells.

TJ: There are clouds of little red fluorescent snapper in the film. How many of them did you actually build?

HS: We only made a few, but we animated them many times at different angles. They were multiplied in compositing. We just animated them at so many different speeds and so forth. Rather than totally switch over to CG when nothing else was CG, it made sense to hand-animate a very small school and then cut and paste that.

Goldblum (left) and Murray check out the hydronicus inverticus (rat-tail envelope fish).

TJ: The puffer fish in the film looks very elaborate.

HS: It was. Whats elaborate about it is that it blows up, and so figuring out and sculpting that material so that we could blow it up like a balloon and get the right shapes was one big engineering issue. We do it a frame at a time with a pump, and lock it off while moving the fins and the tail. And then the other issue is just getting all those spines to stand up. That was an engineering nightmare.

TJ: How many were there?

HS: [laughs] Like a 100. We went all-out. It was always Wes desire that these look like creatures that might not really exist, but youd like to believe exist. So its much more realistic than anything Id ever done. That rat-tail envelope fish, also known as the hydronicus inverticus, was an engineering challenge and design challenge. And another creature that was given background status it was our first one so we tried to make it really impressive was the golden barracuda. It used to be featured in the first part of the movie, swimming in the foreground when those divers appear, in the documentary thats being shown at the festival. It swam from the background to the foreground and then ate this swimming school of starfish. We put in gills and mouth parts that expanded, we made every scale that the fish really has, and attached those to its skin.

TJ: Wasnt the starfish going to be translucent, with a shrimp inside?

HS: Yeah we lost the shrimp part, because it just wasnt going to read. We had a school of them spiraling through the water, spinning themselves. And it was really beautiful, but Wes at the last minute decided it was a long beginning, it was too violent, or something. So thats more background stuff. Hopefully all of that will get out there.

TJ: Thats why we have the Criterion Collection. This article wont include a picture of the jaguar shark, for obvious reasons, but the creature does look uncannily like an unholy merger between those two species. Was the puppet itself a monster?

HS: Yeah. We actually had Ray Harryhausen come and visit our set while we were working on that. He was very happy to see stop-motion being used for a major motion picture, a live-action film. He also was astonished at how big it was. He said that was by far the biggest stop-motion puppet in his memory. It was eight feet long and we had to make it huge, because of the scale of the lenses we were using. Our D.P., a guy named Pat Sweeney, hed actually shot a lot of those submarine movies like Hunt for Red October, and he knew how big those had to be in order to move people through the scale. It wasnt as difficult as, say, the blowfish and some of the other creatures in its individual engineering problems, but the fact that it was so big was difficult in itself. And it was the climax of the movie is this thing going to be a joke, a big stop-motion puppet, or can we make it beautiful and mysterious and pull it off? So it was a huge challenge.

Selicks conceptual sketches would be a great treat on any DVD.

TJ: Where was the animation staged?

HS: This was all done in Marin County. An old friend of mine, Jim Morris, who ran ILM for years he just stepped down their stages were vacant because most effects at ILM are CG, so we got a great deal to go in and use the ILM motion control stages to do the show. It was the first time an outside show, a non-ILM project came in there. It was great. We needed everything they had to pull it off.

TJ: Did you step in front of the camera at all as an animator?

HS: No, not on this show. Id do poses, sometimes, get out there and bend the thing Lets find out what it can do. Often Id do sketches, storyboard things, but the main animator for two-thirds of the movie was Justin Kohn. He was fantastic. Ive worked with him on most of my shows. And then Tim Hittle, you might know his short film [The Potato Hunter, 1990] won an award Tim came in as a second main animator. Ive worked with these guys so long, we just talk about it, do some sketches, do a few tests. I never had done swimming things before, and that may look deceptively simple to the outsider. Its actually pretty complex, how to come up with the swimming motion.

TJ: Did you have time to re-do things if Wes changed his mind, or were you down to the wire keeping on schedule?

HS: No, we were one of the only parts of the film that actually was under control and on time. We did re-do some shots. Concepts change. The little hand-lizard on Bill Murrays hand originally when we animated it, we had it look at Bill and then yawn. And its really beautiful, but Wes in piecing things together thought maybe it was a little too cartoony. So we re-did a handful of shots, and we kept everything available and ready to go again. But we finished at the very end of April, early May, so they had plenty of time.

The little lizard that crawls on Bill Murrays hand is one of the only animated shots that had to be revamped.

TJ: Moving to the subject of your Will Vinton Studio projects whats Moongirl?

HS: Moongirl is an original idea that was conceived by a guy named Michael Berger at Vinton. They had an in-house competition to come up with an idea for short films. Moongirls going to be CG, the first all-CG film Ive directed. Theyre building a CG pipeline, although they plan to continue in stop-motion. Theyre the co-producers of Tim Burtons Corpse Bride. But Moongirl is Im trying to bring some of my sensibilities, give a different look to CG than people have seen. And its also an opportunity for us to learn about CG. If I want to use CG in the future, Ill be a little more familiar with it. But its a beautiful story. Its not at all a cartoon gag-oriented piece. Its kind of slow going, because as I say, were building a pipeline. Were going to finish that up in spring. Itll probably be summer before it gets out to festivals.

TJ: Your short Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions and some of your MTV interstitials are available at the Vinton site. Is your 1981 short Seepage out there anywhere?

HS: You know, I havent put any effort into making that possible. I do think it would be a good idea to get all that stuff transferred digitally. Yeah, theres no way to show that at this time.

TJ: On Fantastic Mr. Fox, the trades are saying Anderson is directing. What kind of job position do you see yourself in on that project?

HS: Its definitely a Wes Anderson film, and at various times hes asked me to direct it for him, and to co-direct it hasnt been worked out. Hes writing the thing with Noah, hell have a big hand in the look and the design of it, and would review story reels and animatics. But I dont imagine hed be a part of the day-to-day making of the film. Hed probably be off doing something else at that point.

TJ: So Coraline is going into production first?

HS: So far, yes. But well have to see how long it takes Wes to get his screenplay done, and where I am at that time. Hopefully I get to do both.

Published by HarperCollins, author Neil Gaiman and illustrator Dave McKeans Coraline will come to the big screen via the wondrous animation of Henry Selick. © HarperCollins.

TJ: When the Coraline feature was announced, I read you had already done the adaptation when you got the rights. It sounds like youve been involved from the get-go.

HS: Yeah. It was set up with Bill Mechanic, and it was originally planned as a live-action film. So we had the option, but not the underlying book rights. So I went ahead and developed the screenplay, based on the book, with Bills input. Coming to Vinton, one of my primary goals was always to bring the project in. So they were aware of it, they liked it, and it took several months of negotiating and so forth to work things out. But one of the best things about bringing it here is Neil Gaiman is very pleased its going to be an animated film. I always felt that was the best place for it, versus live-action with effects.

TJ: So it will be akin to Nightmare Before Christmas, which was all animation, versus James and the Giant Peach, which was an animation/live-action split?

HS: Yeah. Its going to be an all-animated feature.

TJ: When did you first read the book?

HS: I read the book almost four years ago, Id say. The book had not been published, and wasnt even finished when Neil came to me. He was close to finishing. But hed worked on it for many years as a part-time project. It was inspired by his own daughter, and his relationship with her, being a very busy guy trying to write all the time. So I read it it wasnt even the galleys, but the close-to-finished novel about four years ago, and took it to Bill Mechanic whod recently set up as an independent producer after running Fox for a number of years. I convinced both him and Neil not only to let me be attached as director but to give me a crack at writing the screenplay.

TJ: I could see it as a stop-motion feature the moment I read about the Other Mothers button eyes. When did you know you were going to direct it?

HS: Boy Id say within 20 pages. It just felt like, Wow, this is the world I love and know. I think I was very faithful to the book, and Neils pleased with the screenplay, but I definitely had to change some things totally. The book is very frightening at times, and quite creepy. Ive tried to make it a little more spooky and fun while being very true to the material. I had to add another character. When you write a book you can have a lot of interior dialogue. So I needed to add something. And there was something that came from Bill Mechanic that was quite useful: I didnt want the world to be so immediately off-kilter when she entered it, so I save the button eyes. Theyre something that is revealed a little later. So its more of a Hansel and Gretel, this-is-the-best-place-in-the-world-to-be feeling, before the truth about that other world, that other version of Coralines life is seen.

TJ: It is a dark book. Its comic, but its not a comedy.

HS: Yeah. Actually theres a lot of humor, but its very dry. I mean, the talking cat is probably the funniest character, but hes not going for laughs. So I tried injecting a little more humor, and a little more balance with the darkness. I mean, look I want the dark and scary things to be really strong, but I dont want people, especially kids, to feel like theyre going down a well and theyre not ever going to get out. Its not trying to be like The Ring, an adult horror film. I call it a kids horror film. Something that scares the hell out of them but also gives them some good laughs.

Taylor Jessen is a writer living in Burbank. His latest comic is MANIFESTOR!, the tale of an inventory control clerk in an office supply warehouse who gets a radioactive paper cut, grows eleven stories tall and runs amok.